Generally speaking, I don’t drink much green teas because I find them to be relatively one dimensional. Although it was the type of tea that got me started drinking seriously, I now consume less than 100g of green tea every year. That’s one big reason why I rarely drink Korean teas – they are, by and large, green teas. While the ones I’ve had are generally pretty decent, I just don’t have the room or the inclination to drink them with any regularity, so much so that a can of tea I bought two years ago from a Korean farmer still sits in my tea cupboard, unopened. It’s a shame, really, but I have too much tea to drink, so my experience with Korean teas is limited.

Since I was going to Korea though, there was no reason not to drink some local tea. My previous experiences in Korea is that, for the most part, there’s no tea in the country. Even at restaurants, the most you’re ever going to see are some bad teabags. This time I was pleasantly surprised that the quality of teabags in the country has improved – they are no longer the scum of the earth type of tea that I experienced ten years ago. It also helped that I brought my own tea, so I wasn’t very desperate for caffeine. It is rather telling though that at a place like Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf, they only had three types of non-flavoured, non-tisane teas, versus maybe a dozen or more that you’d expect when you’re in California. The local taste is really for coffee, and flavoured teas.

Since this was a family oriented trip, I didn’t have much time to spend trolling teashops. I did find enough time to go visit Insadong, which is a touristy area that sells a lot of cultural goods – paper, ceramics, arts and craft things, and among them, some teashops. The last time I was in this area was over 10 years ago, but not much has changed – I still recognize a lot of the shops that I went by last time, which, in and of itself, is pretty incredible. Some, such as one that sold puerh back in the day, is still selling puerh now. The prices, however, are extravagant.

In fact, tea in general seems pretty expensive in Korea, for reasons I don’t understand. Perhaps it is the tariffs that kills it (if I’m reading correct, tariff for green tea is 500%). Either way, we’re talking about some pretty expensive teas here, with a relatively limited selection of greens that are differentiated primarily, for the untrained eyes anyway, by the youthfulness of the buds. I didn’t hold out much hope for anything too fascinating.

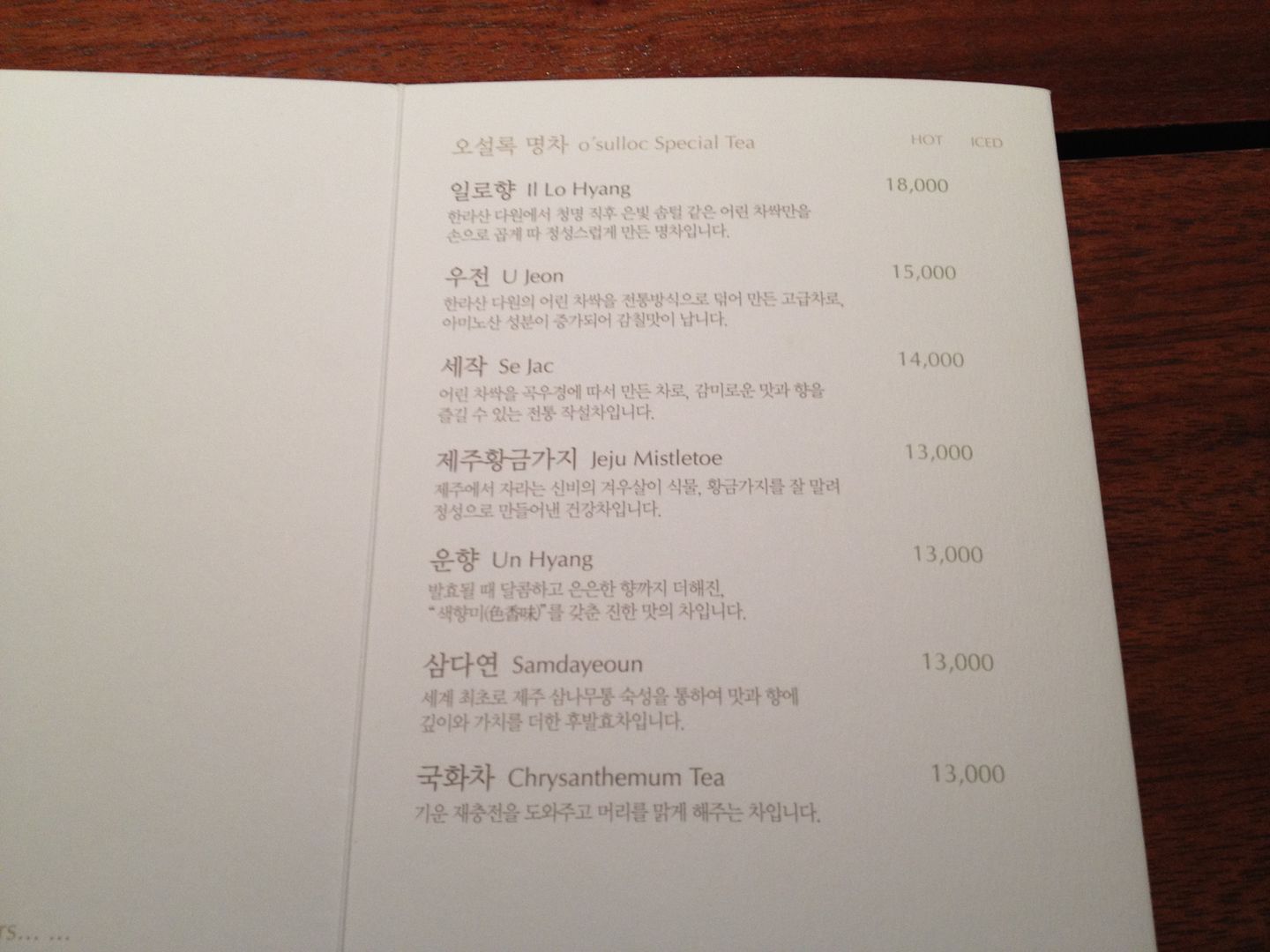

While walking around Insadong, however, MadameN and I ran into a rather large shop that I don’t remember from my last visit. The store is called O’sulloc, which, upon googling it after returning, seems like a big tea producer in Korea. Mattcha, who has been writing about Korean teas for years now, says they used to sell to the Western market, but no more. We went to the third story of the teahouse, avoiding the large crowds at the second floor who were voraciously devouring shaved ice. It was rather quiet up there, and dark, with prices to match the surroundings. Looking at the menu in the dimly lit environment, I tried to pick out what looked the most interesting – we had two teas in the end, the Unhyang and the SamdayÅn.

After a “cleaning” cup of green tea, we each got served our own tray of tea.

Lighting is bad in there, so bear with the bad pictures. This is a picture of the SamdayÅn, although I couldn’t quite tell the true colour of the tea itself, because the interior of both the pot and the cup are reddish in nature, which obscures the colour. The taste of the tea though is very interesting – it is a taste that I don’t think I’ve ever had before. The “post-fermentation”, whatever it is, did something to the tea, and there is also a scent that is probably from the cedar that they stored the tea in. The leaves used for this tea is some kind of sejak base – very small, fine buds. The colour of the leaves is a reddish one – looks a little like a good Oriental Beauty. This is an odd one.

In comparison, the Unhyang is less exciting, tasting more or less like a highly oxidized roasted oolong. The problem common to both teas, really, was the relatively low amounts of tea they used in the pot. I think we each got maybe 3g of tea in the pot, which really was nothing, and was not sufficient to get a good sense of the tea itself. The water used was also lower in temperature to start off with. I think both of these teas, because of their processing, can stand higher temperature and probably would be much more interesting brewed stronger, but alas, that wasn’t the case. At the prices they want for a mere 30g of tea, I find it hard to fork out that much for something that was only decent. A nice curiosity tea, perhaps, but not one I’d go for with any regularity.

There were some other shops that looked promising, at least, but we neither had the time, nor the energy to go through them. I didn’t really get a chance to shop again either, so this trip’s tea activities were relatively limited This is inherently the problem of trying to tea shop in a place you’re not too familiar. The shops that you end up at tend to be in the more touristy areas. You have very little time, and very little information on which shop is good and which one isn’t. You have a limited amount of energy and stomach to try a lot of teas. You are, sometimes, constrained by language barriers. If I had a few months in Seoul, I’m sure I could do better and find more local shops that might have interesting things for less money, but I don’t. At least I’ve spent a fair amount of time shopping for tea in other places, but even then I had trouble getting good tea within half a day.

Now imagine if you ask a friend of yours, going to China for the very first time, to buy you some nice tea while you’re there, preferably some yancha or puerh…. you can imagine what will happen then. Which is why I always tell people don’t ask your friend to buy tea for you unless they know the area really well and they also know tea really well. Otherwise, you’re quite likely to end up with duds that disappoint.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

I took you at your suggestion and have been reading some of your old post-Covid posts. I haven’t been to…