I haven’t been to a mainland Chinese tea fair in quite a few years. Back in the day, I’d go when I get a chance, although in general, they’re all rather samey – a lot of big displays from big producers, plus a whole bunch of smaller stalls from smaller, no name sellers and producers that seem to exist on the sidelines just because. This year I got asked to give a talk at the 2018 Shenzhen Global Tea Fair, originally by Livio Zanini to be part of a panel. However, as that fell through, I figured… why not, I’ll go anyway, so I ended up going anyway to give a talk based on A Foreign Infusion.

One thing to note is that all these tea fairs around the country are done by the same company – Huajuchen, who have a rotating schedule of tea fairs all around. So there really is something to the idea that once you’ve been to one, you’ve been to all – because they’re all organized by the same people who travel around China to do these. Shenzhen is one of their biggest, and it’s big – about six halls worth of tea stalls. This is what parts of one looks like

I got there early, before they formally opened, so I took a quick walk around before any customers showed up. Tea fairs in China are part trade show, part consumer expos. For the bigger producers, I think it’s a branding exercise. For the smaller guys, it’s an important retail outlet. Last time I went to a Chinese tea expo, probably ten years ago or so, it was mostly puerh. These days, there’s a lot more white tea and liubao, although puerh is still quite important. Interesting to note though, some of the biggest brands in pu, like Dayi, don’t seem to be there – perhaps there’s no real reason to splash a bunch of money on what has to be a lavish stall (because they’re the biggest brand after all) and the return on such a stall is minimal, since everyone already knows who they are.

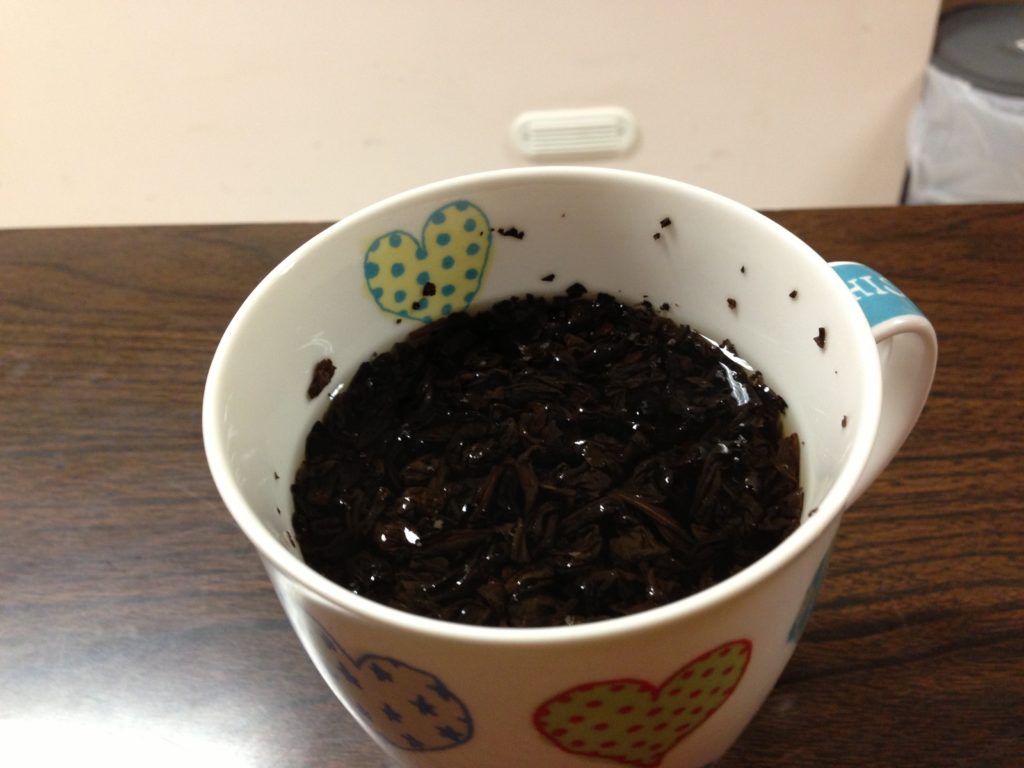

For someone like me, the more interesting stalls are always the small ones. The big brands you can find everywhere, the small ones you never see. Unlike in the past, however, when I’d happily spend hours sitting at stalls drinking this year’s production, these days I’m really not very interested in new-make puerh. Instead, I looked around for older stuff – there isn’t much that is interested in the older puerh category, since they look kinda like this

Which are stalls that claim to sell “old tea, dry storage”, mostly pu from the 90s or 2000s, at pretty inflated prices and questionable quality. I can find cheaper or better elsewhere, no thanks.

There are also some interesting, new concepts like this one

What the hell is “Tea York Hub” you ask? Well, the Chinese name makes more sense – “Haochacang” or “Good Tea Storage”. Basically, this is a rent-a-storage service. They’re not aiming to make money from selling you tea (although I think they dabble in that too) but they’re there to sell you tea lockers where you can store your tea in a climate controlled environment. Pretty brilliant, actually, capitalizing on people’s collections without taking on the risk of actually holding onto 1000 jians of Dayi 7542s. Dayi prices in recent days, for example, having been taking a bit of a dive.

After I gave my talk I ended up doing a few more rounds and ended up trying out some aged oolongs at a few stalls. Whereas I have a lifetime supply of old Taiwan oolongs, aged Wuyi, good ones anyway, are much harder to come by. I did end up at a guy who had some decent 15 years old aged Wuyi, and I bought a couple small cans. He’s one of these smaller producers with a store in Shenzhen. Maybe I’ll talk about the tea another day.

Yeah whisky prices have been leaking too, as well as luxury watches. I wrote a post maybe a decade ago…