.. and bad teas are bad in their own special ways.

Paraphrasing Tolstoy only gets you so far, but in this case, I think it works. Good teas are indeed mostly similar – they are strong, have good body, last a lot of infusions, hit all parts of your mouth when you drink it, and most importantly, taste good. Some might throw in good qi as a bonus, but not every tea has qi, not even good ones (good luck finding qi in a longjing). Nevertheless, like A student papers, there’s not a lot to say other than “it’s good”. You can wax philosophical about how good it is, but that’s not strictly necessary.

Likewise, true failures of the worst kind, the Fs of teas, are also easy to deal with. They’re so bad that they do not merit any kind of time to examine – everything is wrong. They are easy to dismiss.

It’s really the middle ground – the Bs and Cs and Ds of teas, that take the most time to analyze, to grade, and to judge. They have flaws, sometimes minor, sometimes major, but they are flawed in different, diverse ways. Most importantly, for those of us buying teas, they might be bad in ways that are not easy to spot right away. Using the metaphor for paper grading, it’s like a ten pager that starts out strong and then, by page 4, falls apart, contain plagiarized passages, has no proof, can’t spell, etc. You wouldn’t know it if you only read the first couple pages, but if you look more carefully, the problems can be there and be really obvious.

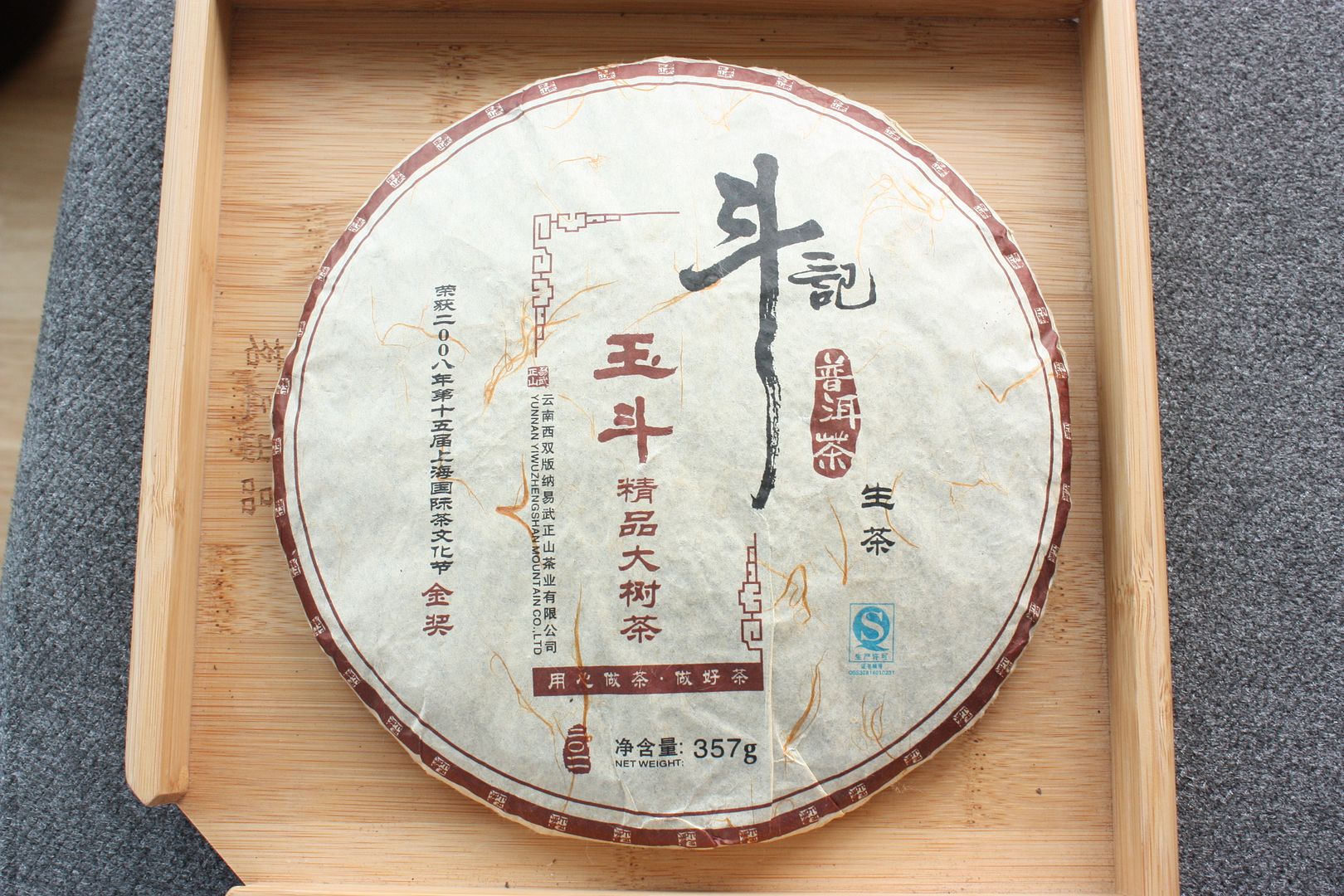

I just tried a few cakes I bought off Taobao recently, and they are all bad in different ways, which is what prompted this post. One, a supposed Yiwu that’s got some name recognition, is bland – seems to be a product of bad, dry, and aired-out storage, even though it has good throatiness. The other, a bulang, packs strong flavours but is intensely, intensely bitter. Yes, it might go away eventually, but probably not, not fast enough anyway. A third has a weird flavour that I associate with strange mainland storage – it’s a sample the vendor threw in, and it’s just, well, strange. Unfortunately, none of them were worth my time, and all of them were bad/strange in their own ways.

Then there was a dahongpao I received a while ago as a gift. These days, all mainland yancha arrive in pre-packed packets, and they are virtually indistinguishable from one another. Gifts can run the gamut from really great tea to really poor. This one, unfortunately, leans on the latter. It’s bland – just not rich and full enough to be called a dahongpao, and is probably just some cheap yancha from the outlying areas.

Learning to spot these things take time, effort, and usually some tuition. It’s very easy to be led down the wrong path by the wrong vendors. This is especially true if you happen to visit mostly one vendor for your teas – if all the teas are bad in the same way, it’s not easy to figure out that it’s actually a sign of poor quality, as opposed to just the way it is. Take bad storage for example – you won’t notice a storage problem if all the teas you have share the same type of storage problem. In that case, you’d just think that’s how things are. Unless and until you’ve tried something else, and it’s totally different, do you realize that something is wrong with the original teas you’ve had. Figuring out what that is takes even more time. The same can be said of teas that claim a certain place of origin, but isn’t actually from that place, or teas that are supposedly processed a certain way, but isn’t. Then there are just the teas that are bland or low quality. All of these require comparison to highlight. So comparison is the key to learning how to spot bad tea.

The job of any vendor is to sell you the tea they’ve got, so in tasting notes you’ll always see things highlighted – aromas, mouthfeel, or worst of all, qi, that ephemeral quality that most people have never experienced, or only think they’ve experienced. For that bitter bulang I just talked about, for example, the vendor might say it’s long lasting and powerful, never mind that it’s like swallowing a bitter pill every time you take a sip. For that Yiwu that I thought was weak, you’ll get notes like “floral and penetrating” because it’s got a bit of throat action going on. The dahongpao I just referred to as bland would be “fruity” and maybe “delicate.” As for qi, out of 100 teas 99 have no qi to speak of – drinking chicken soup can equally give you that rush of warmth and sweat that some point to as evidence of qi. Qi does, I believe, exist in some teas, but they are rare. That’s another post.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

I took you at your suggestion and have been reading some of your old post-Covid posts. I haven’t been to…