So, having stared at the tea for a while, it’s time to drink. I could talk about smell, but I think that should really go into a separate category as it’s not as useful and informative. I should note that while this sounds rather systematic, normally when I drink tea I don’t really think about any of these as a process or a series of steps — they just happen more or less naturally. Too much thinking is, I believe, bad for tea drinking.

Drinking tea is not like drinking wine. You don’t just open the bottle up, pour, let it air a bit, and then taste. How the tea comes out depends on what you put in, and the inputs are 1) leaves and 2) water, all through the use of some teaware. So the variables, in addition to the leaves, are really water, vessel, and method.

I think there is probably no optimal way of testing a certain tea. My rule of thumb these days is to look at it, evaluate it, and estimate how I would brew it. I think the best way to make a new tea that you’re not familiar with is to make it like you would normally do for that style of tea. The reason I say this is much like how audiophiles listen to a few recordings they know well to test a new system — it’s familiar to you, and it’s what works for you. I also say this because water can be a big contributor to the taste of a tea, and how you manage your brewing is dependent on your normal water source. If you always use filtered tap water, then there’s no good reason why you should bring out the $10 bottle of spring water for a new tea you’ve never tried. In fact, you will not be able to tell if the tea is any good, because you are not familiar with the water. Also, as the water changes, adjustments need to be made for how to brew. Lastly, if you normally use filtered tap, for example, then you should use that to check to see if the tea will be good using your normal water. If it won’t, then the tea is not for you, no matter what others say.

The same, I think, can be said of vessels. I used to subscribe to the theory that when testing new tea, one should use a more neutral teaware, such as a gaiwan. This is because gaiwan, being made of non-porous porcelain, does not impart any particular taste to the tea, making your evaluation more “true” to the original taste. But then, applying the same logic I used for water to teaware — if you normally only use pot X for tea Y, then why are you, all of a sudden, using a gaiwan for tea Y? It’ll change the flavour (and sometimes significantly so) so don’t mess up what you know.

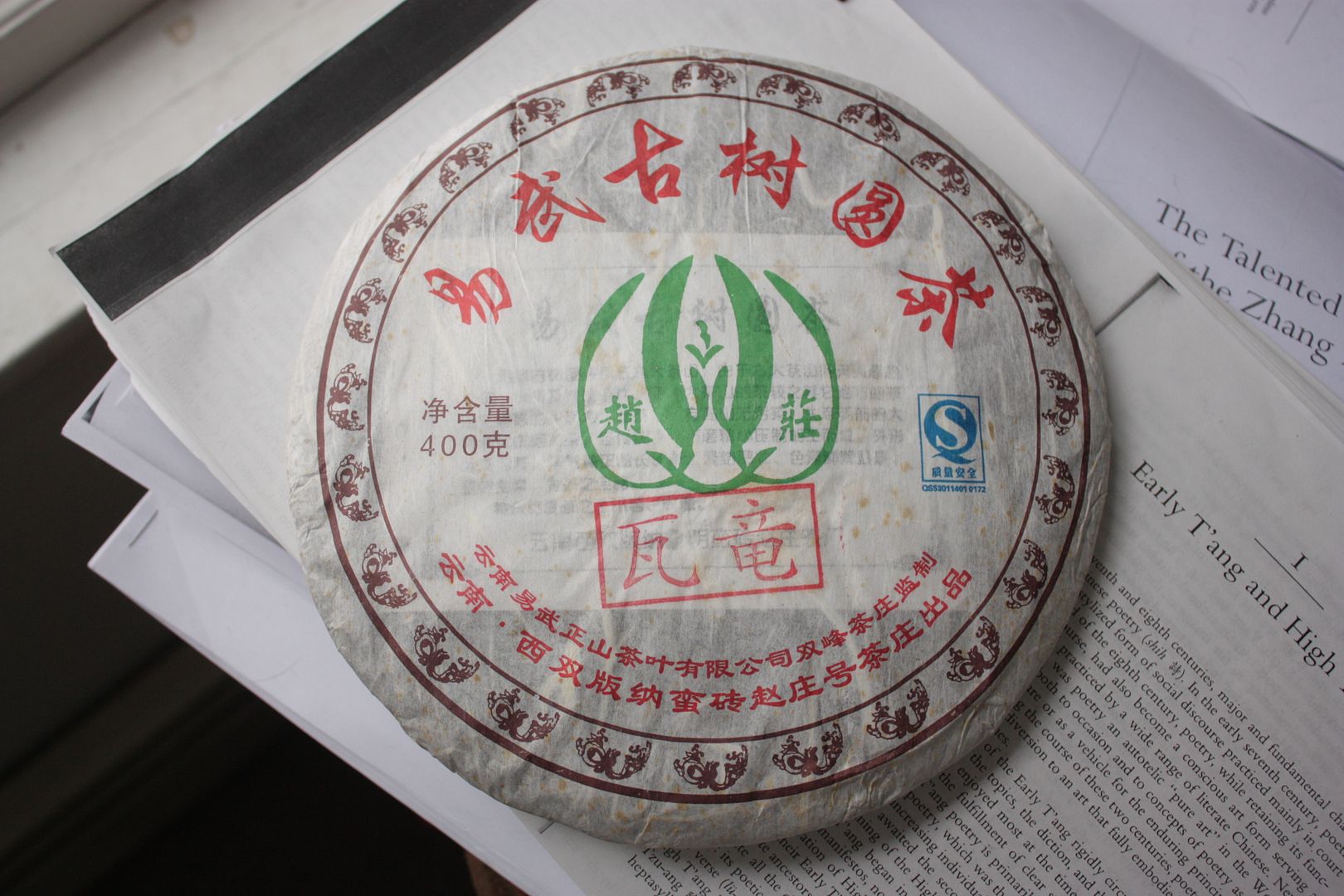

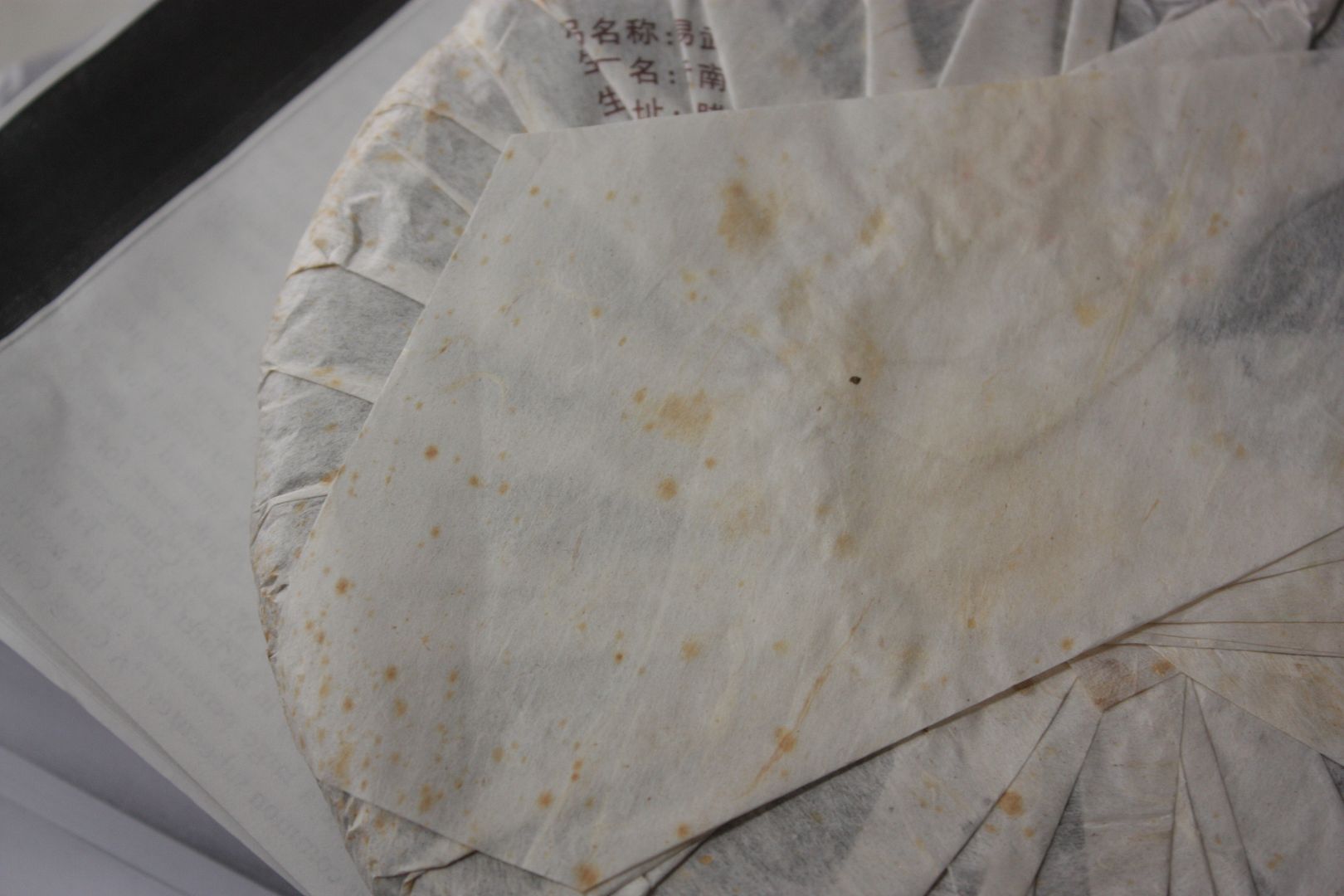

In terms of brewing parameters, this can be a little more tricky, because that can sometimes change dependent on the tea — the roasting level, aged-ness, etc, should all affect how you brew the tea. This is why looking at the tea is important — it gives you the clues you need to figure out how to brew it. Adjustments can be made, but once started, it is hard to go back and fix a session with one tea. It’s better to get it right the first time.

So what do I actually look for, now that we’ve got the more technical stuff out of the way?

I think I can personally break my tasting down to two parts

a) Looking for problems. I think the first order of things for me is to look for problems in a tea. This can be any number of things — over roasted, in the case of oolongs, sourness, bitterness without huigan, off flavours, smoke when there shouldn’t be smoke, weird tastes/smells that are not natural, thin body, any feeling of discomfort, etc. The list is quite long, and can include any number of things. Some are more of a “sin” than others — smoke in young puerh I can tolerate, for example, up to a point. Likewise, a bit of sourness in an aged oolong can be ok, depending on other factors. Negative things, however, are almost always my first impression of a tea when I try it. This, of course, starts with the smell — you smell the brewed leaves, you smell the liquor, and then you taste it. Once you’ve had enough teas before, just smelling something can give you a fair idea of what’s coming your way.

b) Tasting for goodness. I think only after I get the negatives out of the way do I feel the more positive side of things. They go, more or less, hand in hand. In some ways, my definition of a good tea these days basically means a tea that doesn’t have any obvious faults. If it’s got a good body, no odd/off flavours, sourness, unpleasantness, or any of those sort of things, then it’s already not too bad. After that, it’s really a matter of personal preference. Do you like the fragrance of one over the other? Do you prefer stronger or weaker roast? Do you expect a kind of body over another? Since these are all variables that are dependent not only on the tea itself, but also on the way it’s brewed, I won’t go into them.

Another thing I do with drinking tea is to push them to the bitter end – these days, this usually means at least two full kettles worth of water. I think it’s often the latter infusions that tell you the true taste of tea. Any tea can be great the first two cups. Will it last for twenty though? The ones that do are, I think, inevitably better in other respects as well.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

I took you at your suggestion and have been reading some of your old post-Covid posts. I haven’t been to…