So it seems like those crafty Chinese finally found a way to make some money by acting as middleman between that emporium of all things Chinese, Taobao, and the Western buyer who wants stuff on there. For those of you who don’t know, Taobao.com is basically China’s eBay, only worse. Since it does not charge listing or final value fees, anybody can list pretty much anything on there, and much of the business on Taobao is conducted off-site. What it is, then, is basically a huge online catalog, and if you like something there, you contact the buyer and arrange a deal, often with a discount off the Taobao listed prices.

That is if you’re in China.

Since I am not in China, and most of my readers are not either (by definition, because Xanga is still censored,) buying from Taobao requires more work and less discounts. In the old days there was just no way, unless you want to arrange a bank transfer, etc, which are all too much hassle and too much risk. These days, there are a bunch of new proxy service that have sprung up that will help you buy stuff off Taobao. They charge a 10% fee on the value of the item, and will help you arrange payment and shipping. I’ve used one before and it worked quite well, and from what I’ve heard, other services (some in English) will also do the job.

For the tea drinker, this is quite a boon, because for the first time it is possible to have a selection far, far wider than whatever is available through a select number of vendors. Places like Yunnan Sourcing have been providing a fairly wide selection for a while now, but this expands the selection by multiples.

How, though, do you buy and choose tea from Taobao? That’s always a hard question. I thought it might be useful to talk about it, since I’ve talked to people who are getting quite excited about the prospect, and rightly so.

Let’s talk first about the scope. What I think Taobao is good for, mainly, is puerh, especially cakes of a more recent (past 10 years) vintage. While you can find more oolong, green, wuyi, and all other kinds of tea there, in general I would be very cautious buying those off Taobao. The main reason is because by and large, the other kinds of tea are immensely difficult to distinguish between one and another. Physically, the difference between a $10/kg and $1000/kg dahongpao, for example, isn’t really big enough so that you can tell right away on pictures, especially when you consider the potential for photoshopping, bait and switch, and other things that can happen. If you really want to buy loose leaf tea, buy small amounts, ask for samples, and in general, buy at your own risk.

So, you don’t read Chinese. How do you get to the tea anyway? Here’s the link in its full glory

This is the link to Taobao’s puerh section. If you want to go to the section for other teas, with over 400k items, you have to navigate there, but once again, I’m really not sure if it’s such a good idea.

So you’re in the puerh section. Where do you start? Well, let’s take a look

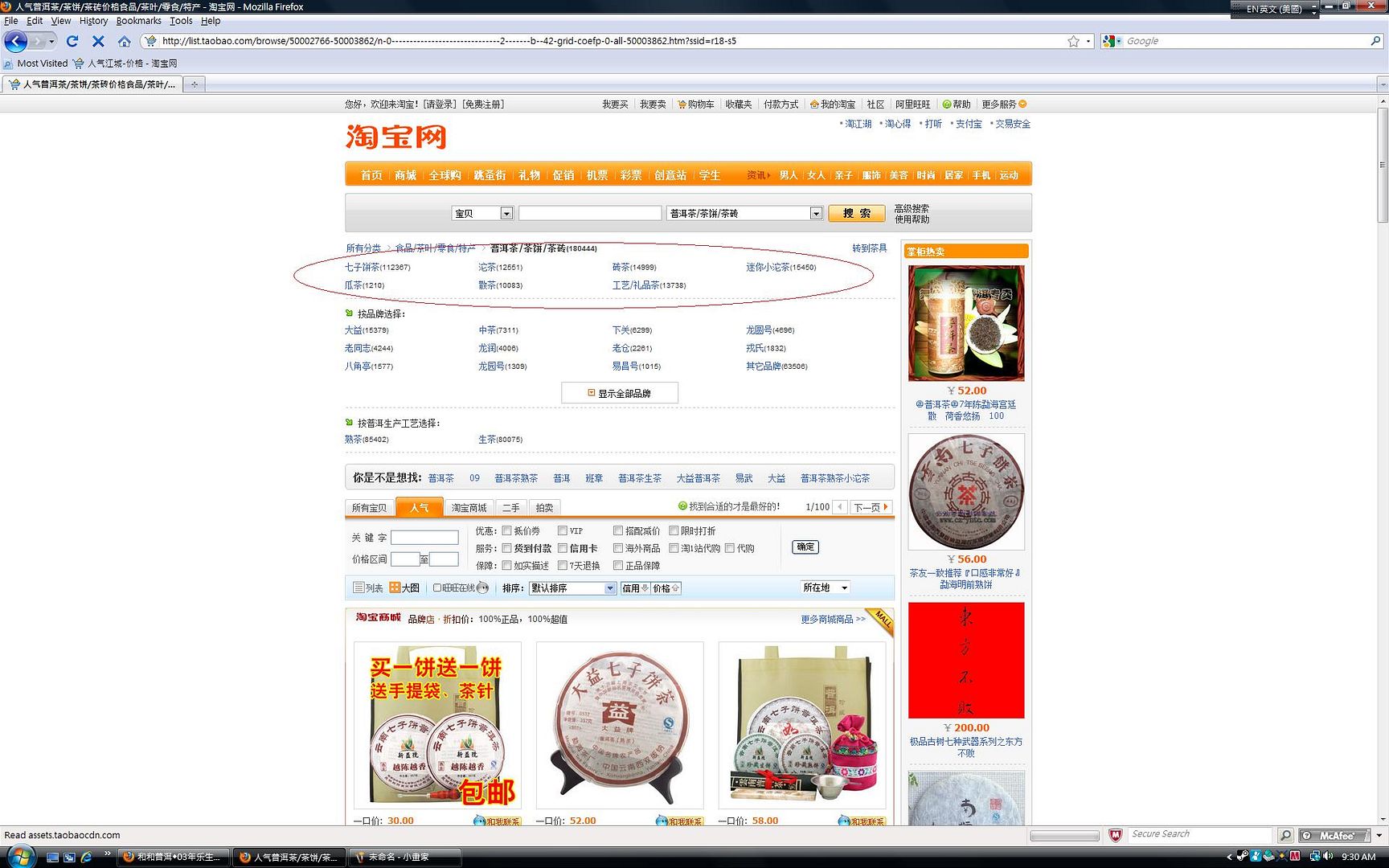

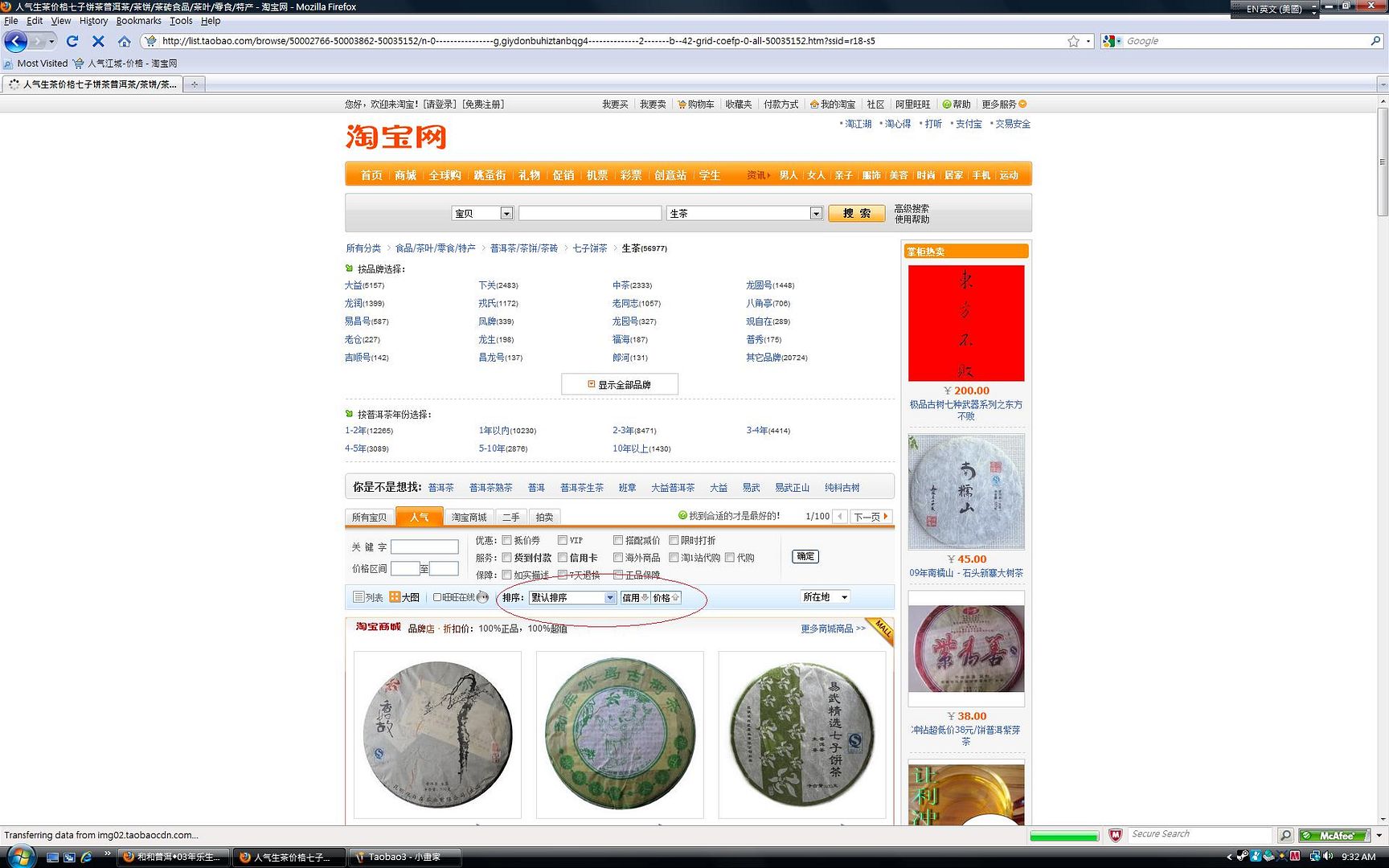

This is the basic screen. The bottom is where the listings start. The top, however, is where you navigate, and it’s much more important. There are three categories that they use to subdivide the cakes, and I’ll go over them one by one. The first, circled above, is the type of puerh. They are, from left to right, round cakes, tuocha, bricks, mini tuo, melons, loose tea, and what they call “artistic” tea, which really means super compressed junk (they’re called that because they are used as decoration.) Now, the second category:

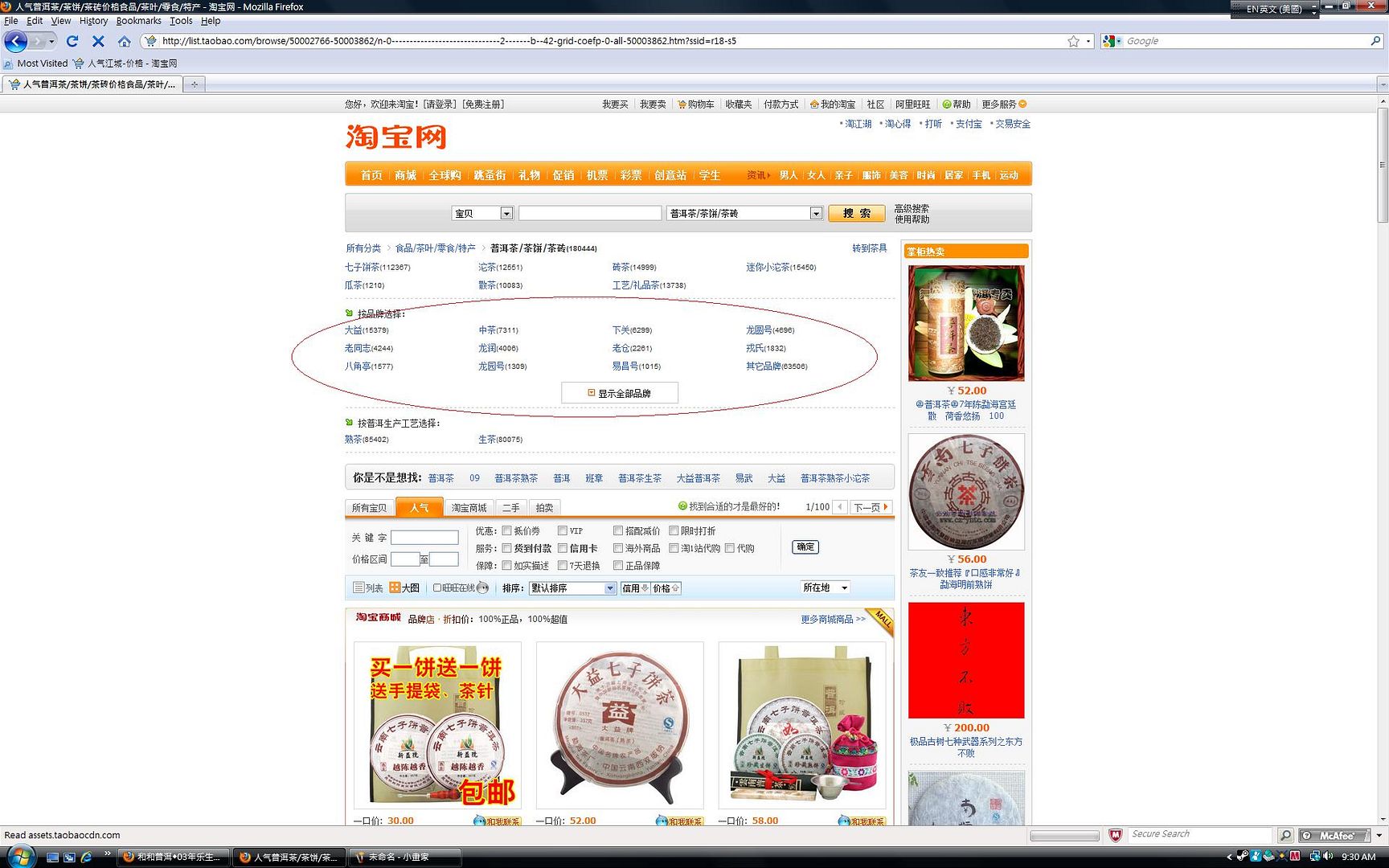

These are the brand names. If you know what you want, you can select one of those to narrow down the list of items you have to go through. The list is long, and the orange icon with the + sign will give you a full list of brands, which includes a list of 28 major brands, plus a “misc.” that includes more items than the rest of the brands combined. I generally don’t search by brand, especially since I like the smaller factory stuff.

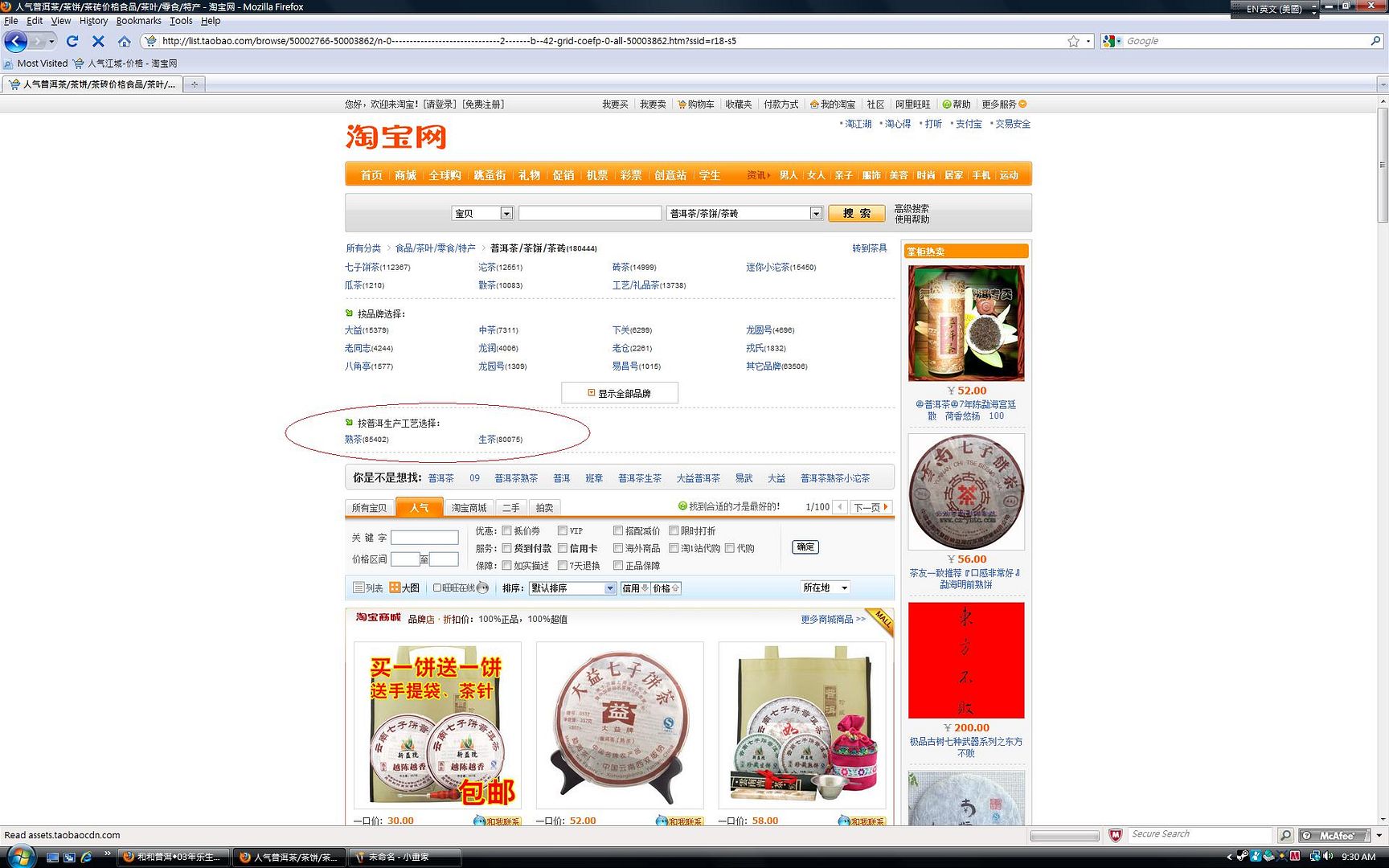

The third category is the most useful — raw, or cooked. Cooked comes first, raw second. This will instantly half the number of items you need to look at.

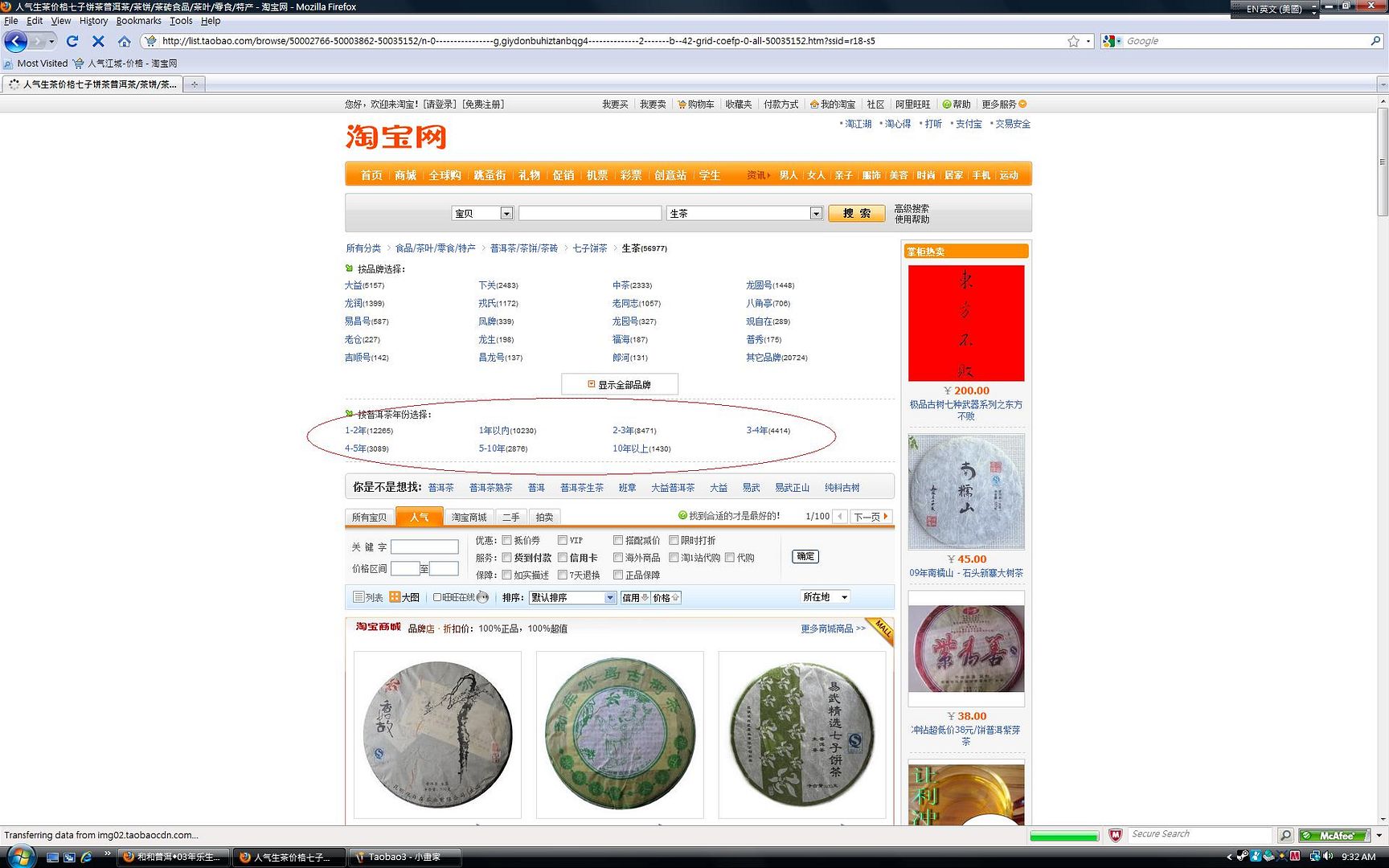

Now, what they don’t show you is that if you pick a style (i.e. cake, brick, melon etc) you will have one more option:

This lets you select the age of the cake. If you know you want something that is, say, from 2007, then you can use this to narrow it down. However, this is self reporting, and since listing stay on the site for quite a while, I can imagine some needing update and never gets it. It’s useful for narrowing down the list further though.

Once you’ve narrowed your list down a bit instead of the tens of thousands of cakes, you’re ready to browse.

There are some navigational tools that you can use right above the cakes, but most are fairly useless. You can specify what type of item you want (i.e. auction, buy it now) but I don’t think we need to go into all that. If you need to, you can go to the dropdown menu I circled above and choose the option you like — arranging it by highest or lowest price first.

Let’s leave this for now. Next entry will be about actually looking at items.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

Interesting.... would 250C in my oven work?