So last entry we stopped at actually looking at listings. Let’s now turn to those.

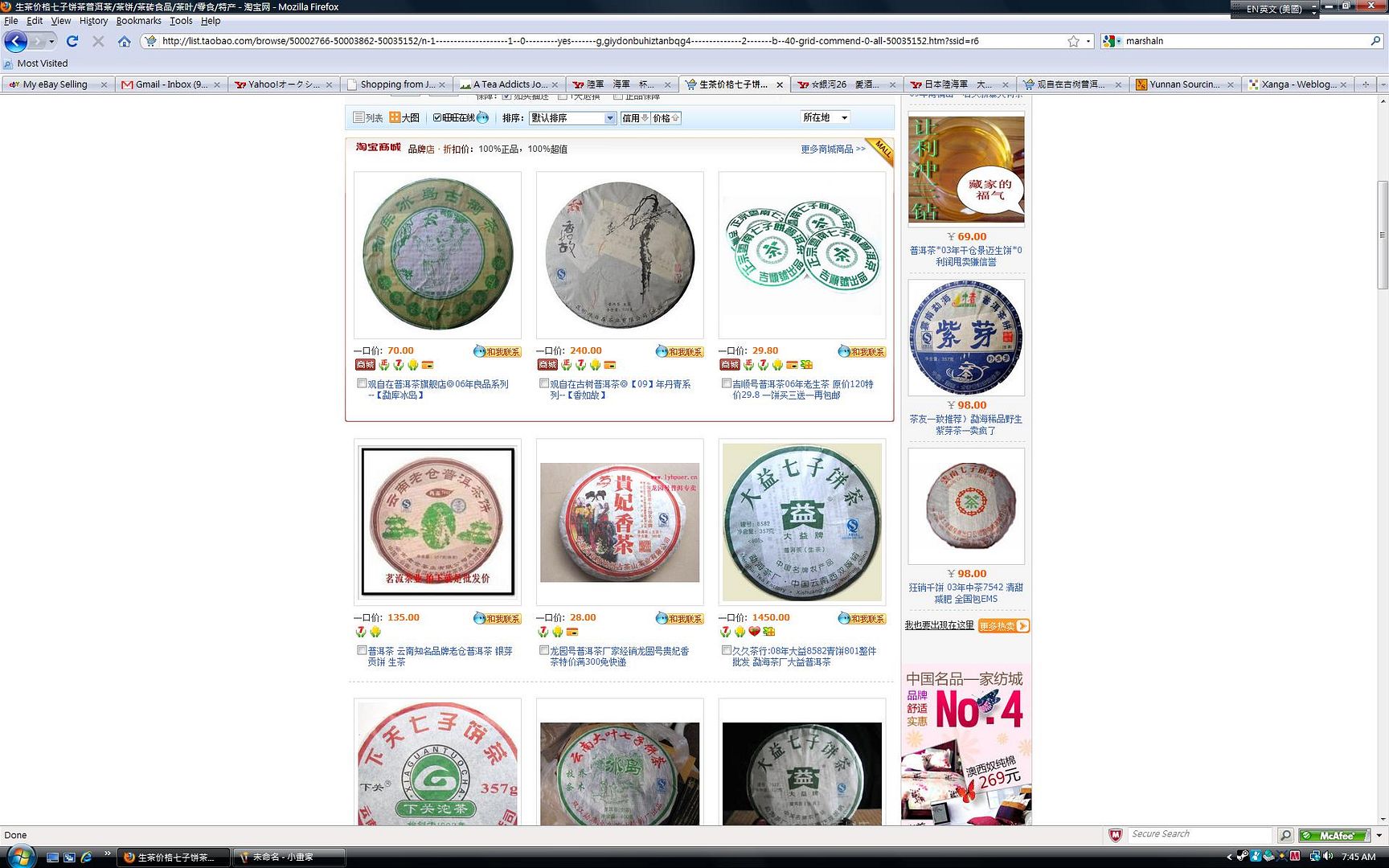

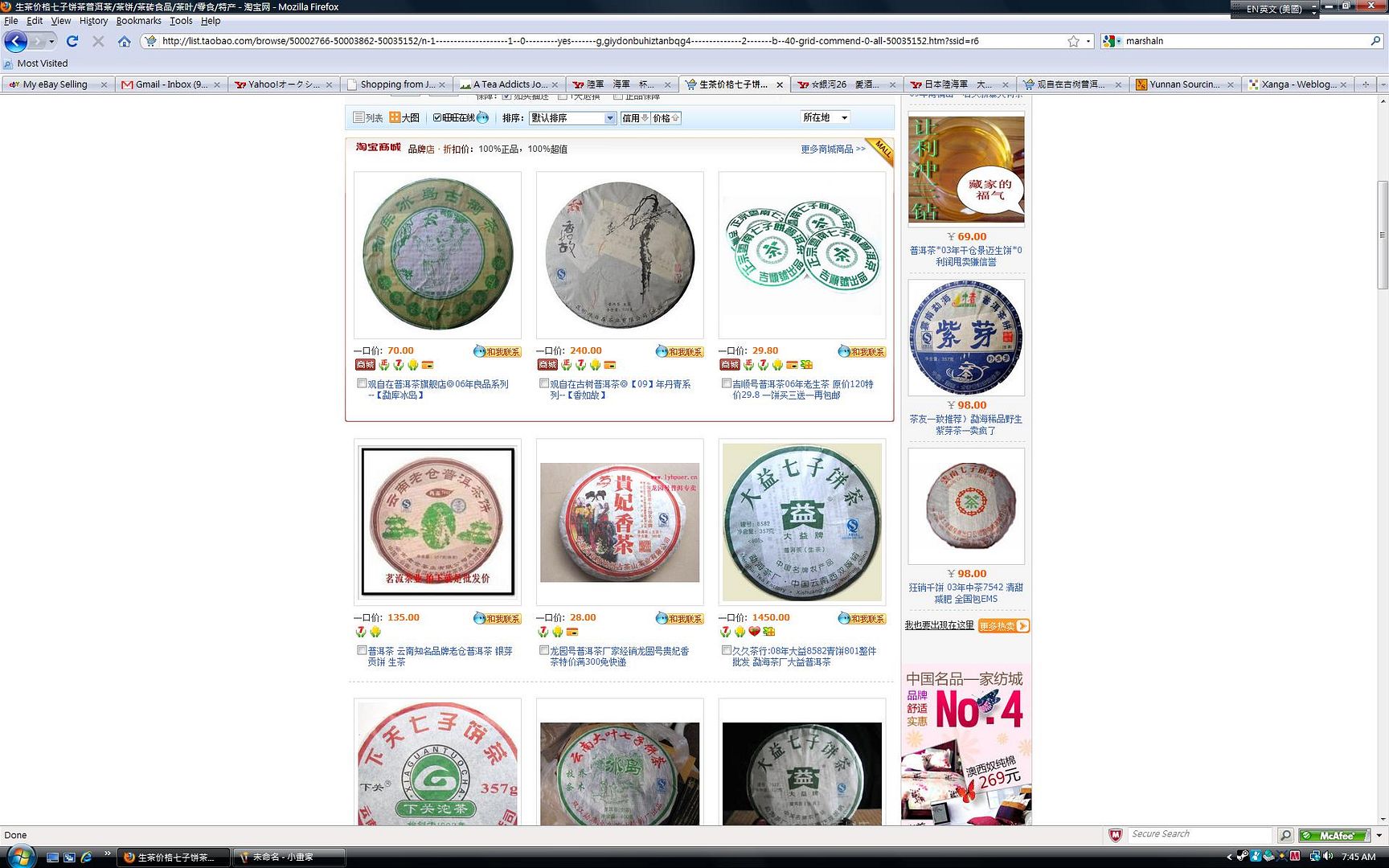

Over the years pictures on Taobao has really improved. I remember when I was in China in 06, very often the Taobao listings would have no pictures at all, or a really bad, grainy, and small picture that might as well not be there. Since then, most listings have gained multiple pictures, and now as long as you believe what’s in the listing, you can find some pretty decent looking photos to rely upon. When you scroll down from the “search” menu to look at the listings, it’ll look like this

The ones in the center are whatever listings that show up under your filters, while the ones on the right sidebar are “related” or “promotional” products, which means they might have nothing to do with what you were looking for. Obviously, go with the ones in the middle. Now, let’s try one of these listings.

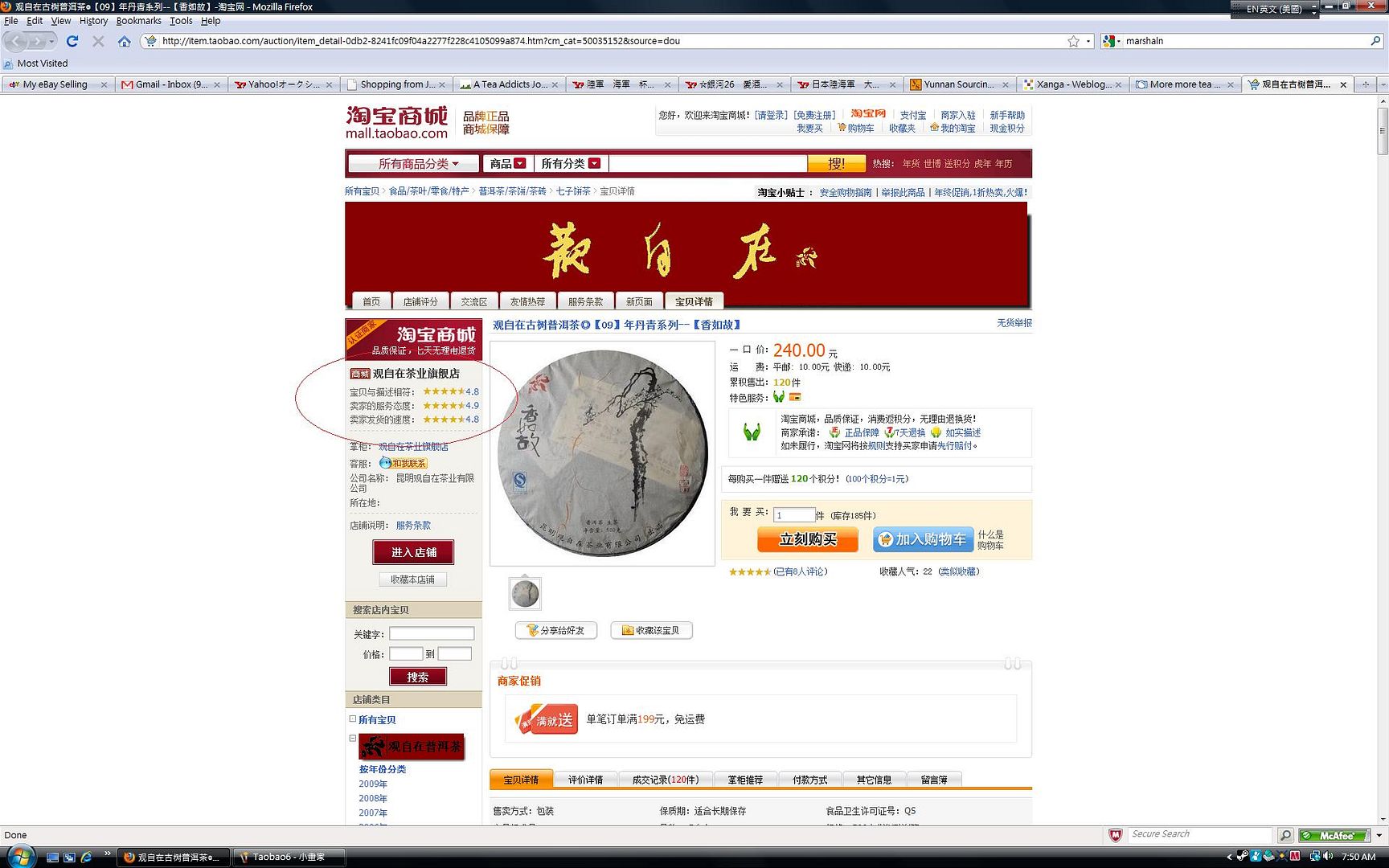

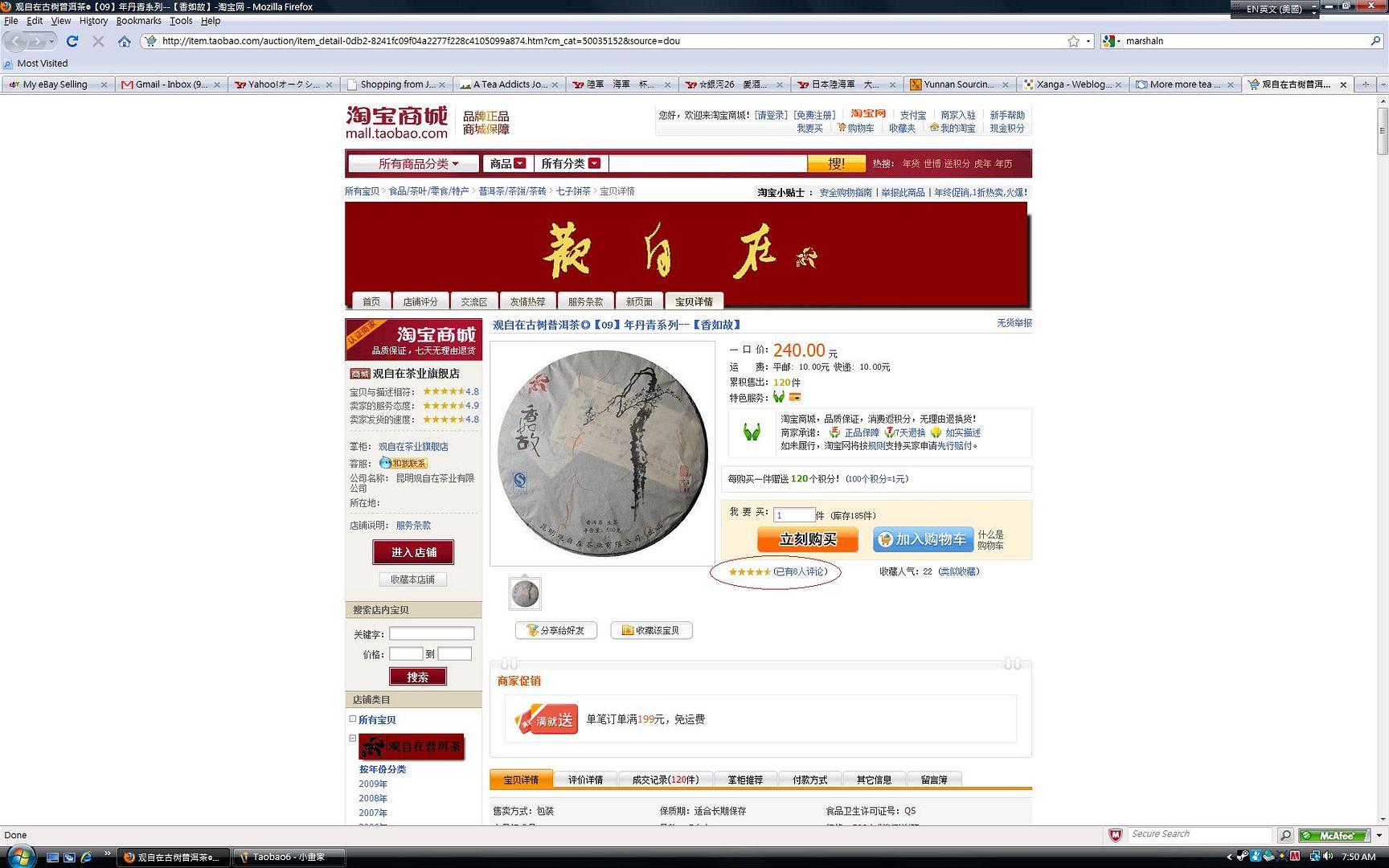

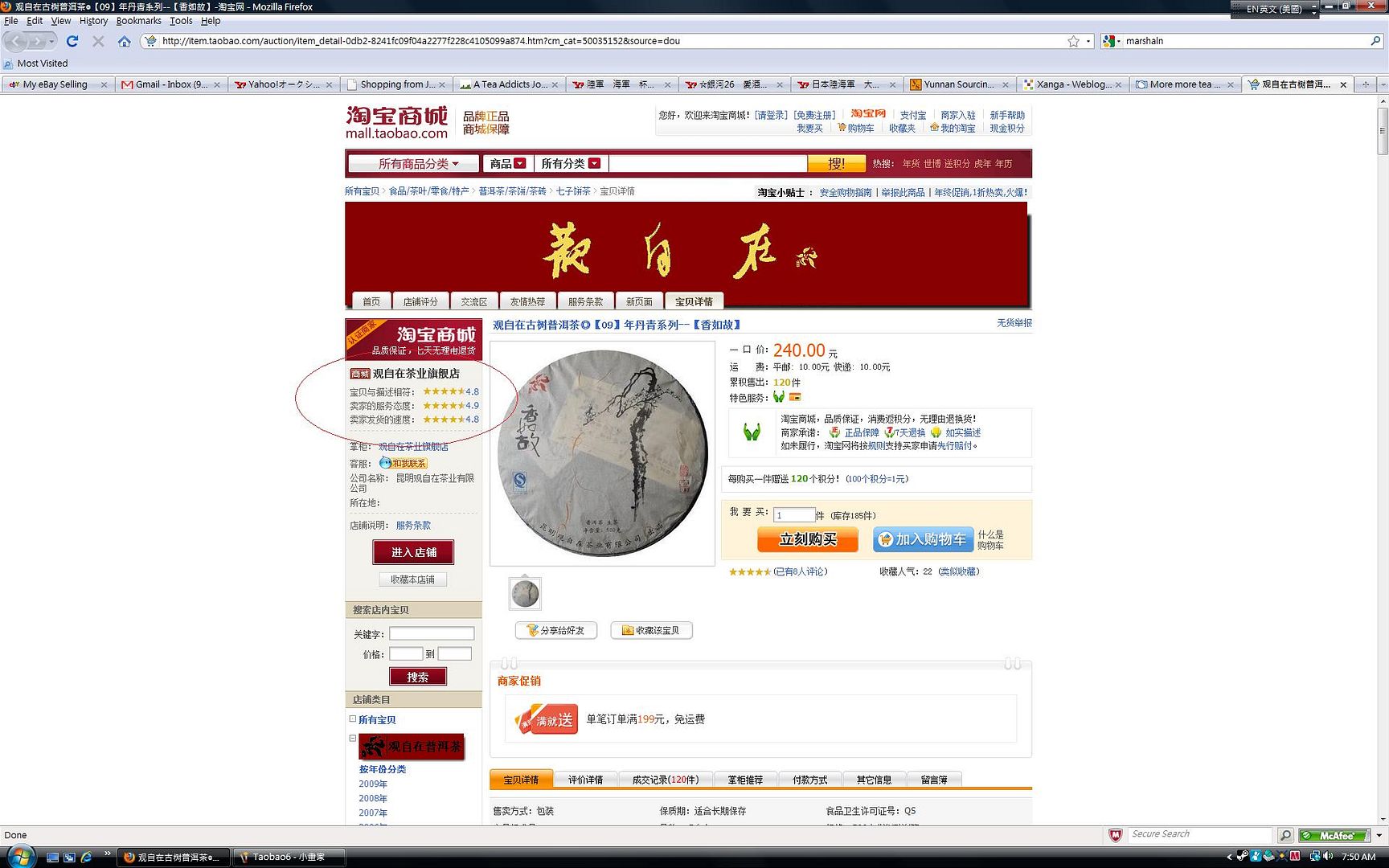

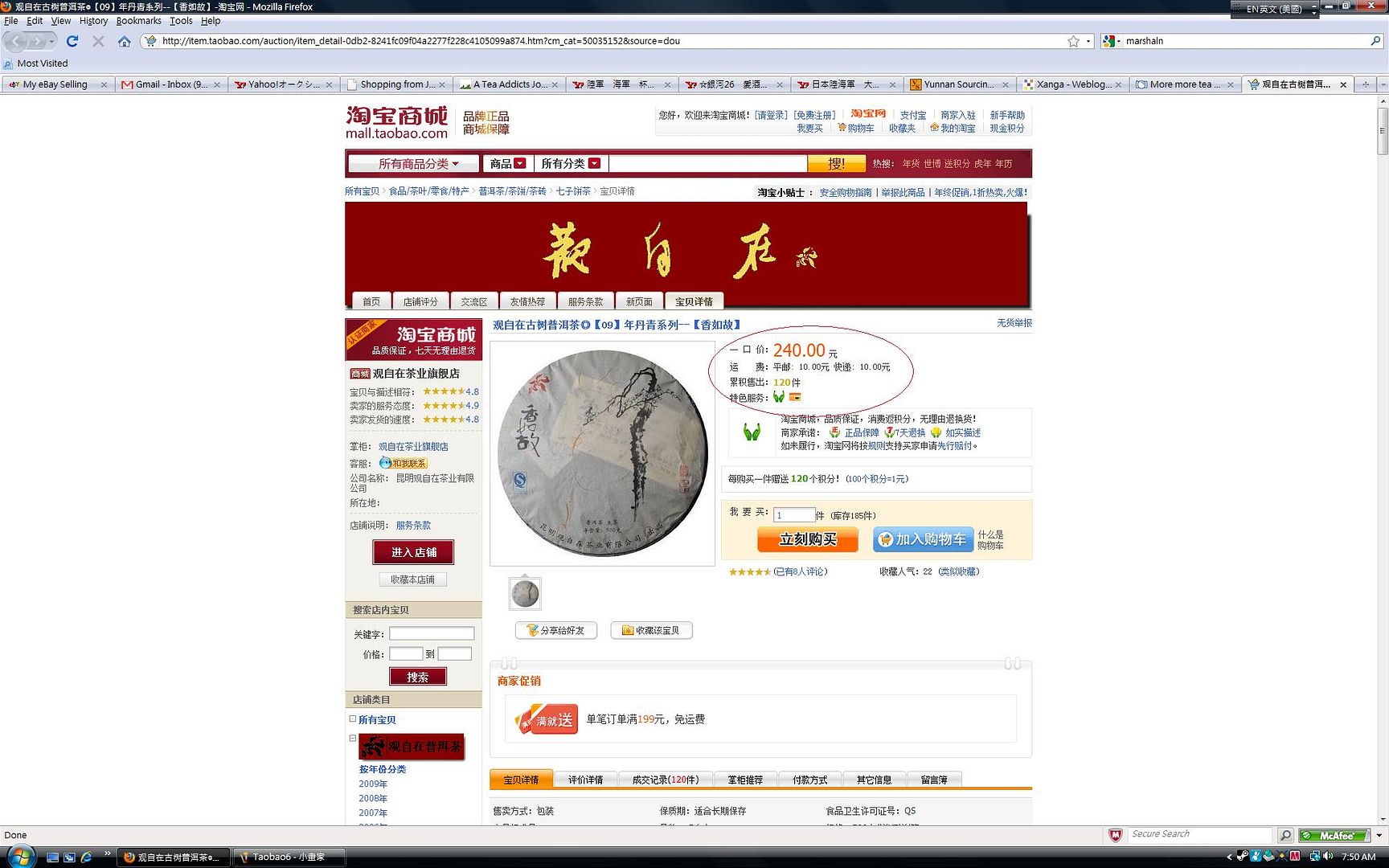

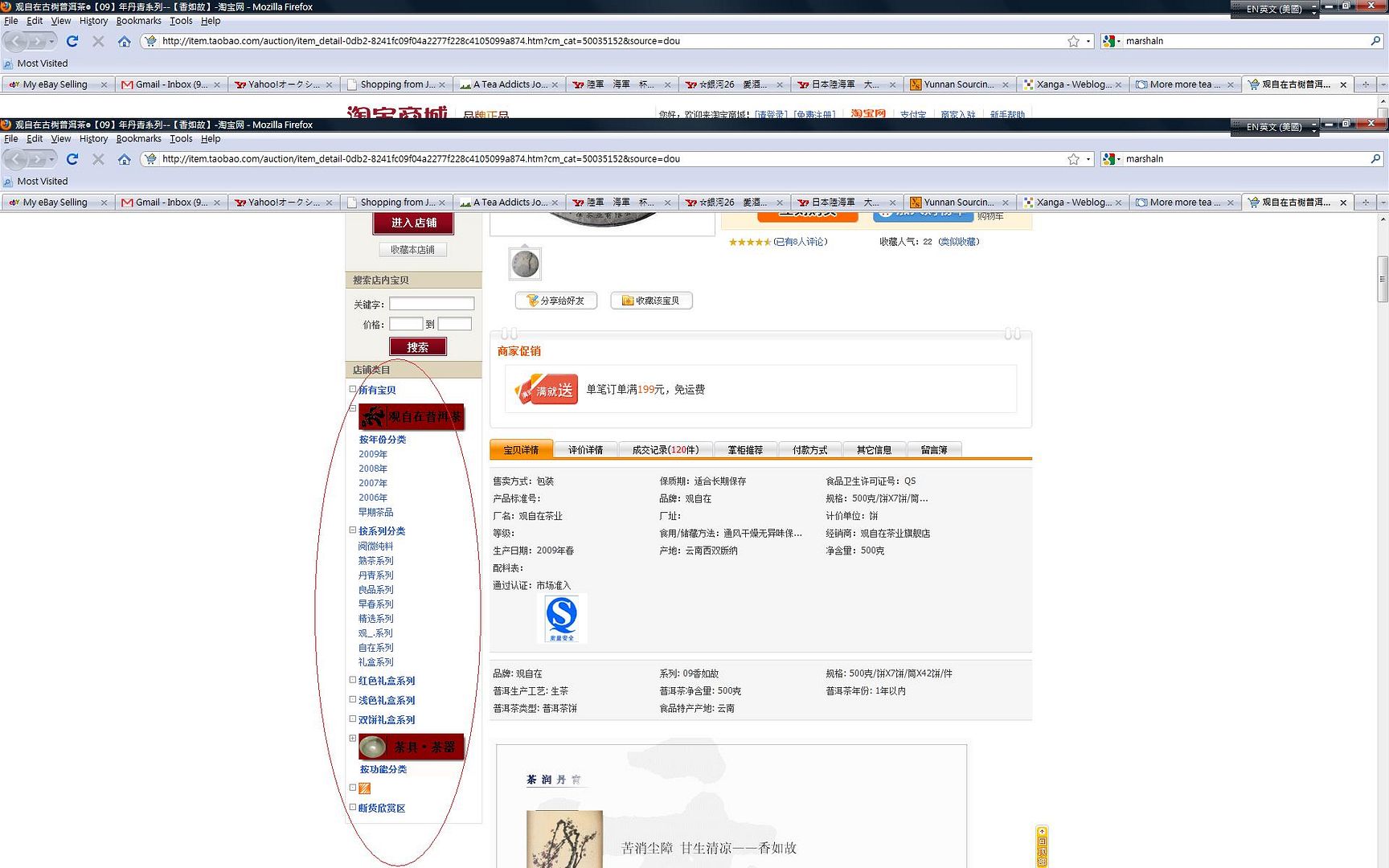

Now, once you’ve been through a few listings, you’ll notice a few things. First, the listing layouts change. Here, the sidebar is on the left, while the listing info is on the right. That’s not always true, and it seems like Taobao allows seller a great deal of flexibility in customizing their listing. This is, I suppose, both good and bad, in the sense that it can make it a little harder to navigate, especially if you don’t know Chinese. There are a few things that are constant, however. The circled area above is a seller’s feedback. This is in the newer system of stars, sort of similar to eBay’s. The older system just shows feedback rating numbers, which, of course, is pretty useless. A seller with low feedback is not necessarily worse — he’s just a lower volume seller. So far, I haven’t been socked in buying things in the sense of having my money taken but no goods delivered. I have, however, bought not very good tea, but that’s an entirely separate issue.

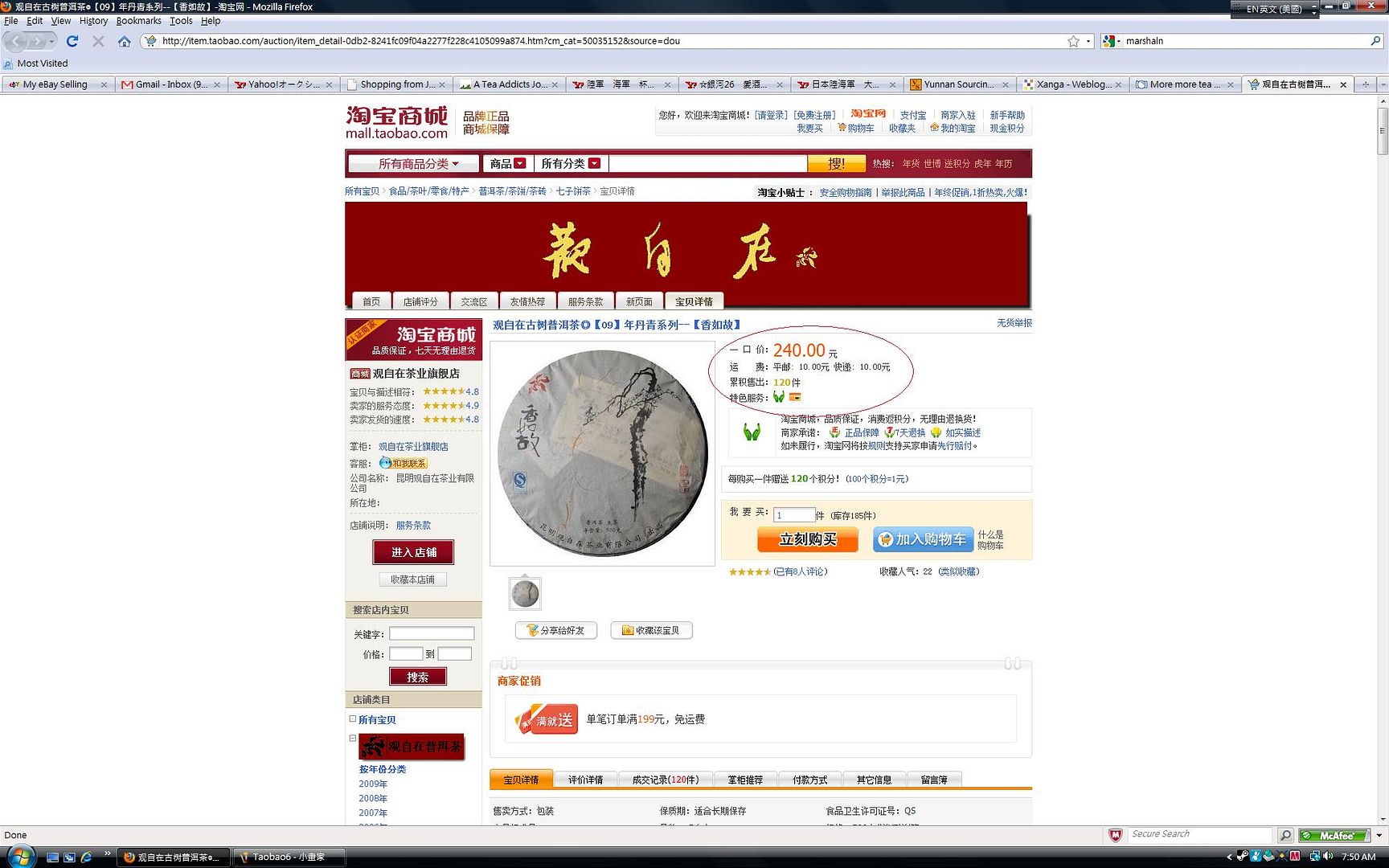

Now, most proxies will do this for you, but this is the part that really matters, the price:

Along with other vital info, that is. The big red number is the price of the cake (which is almost always per cake), with the shipping cost right under it in small print. The number in yellow, though, is the number of times this item has already sold. So for this cake, they’ve sold 120 through Taobao, which is relatively high, especially since Taobao often operates off-site when it comes to final transaction.

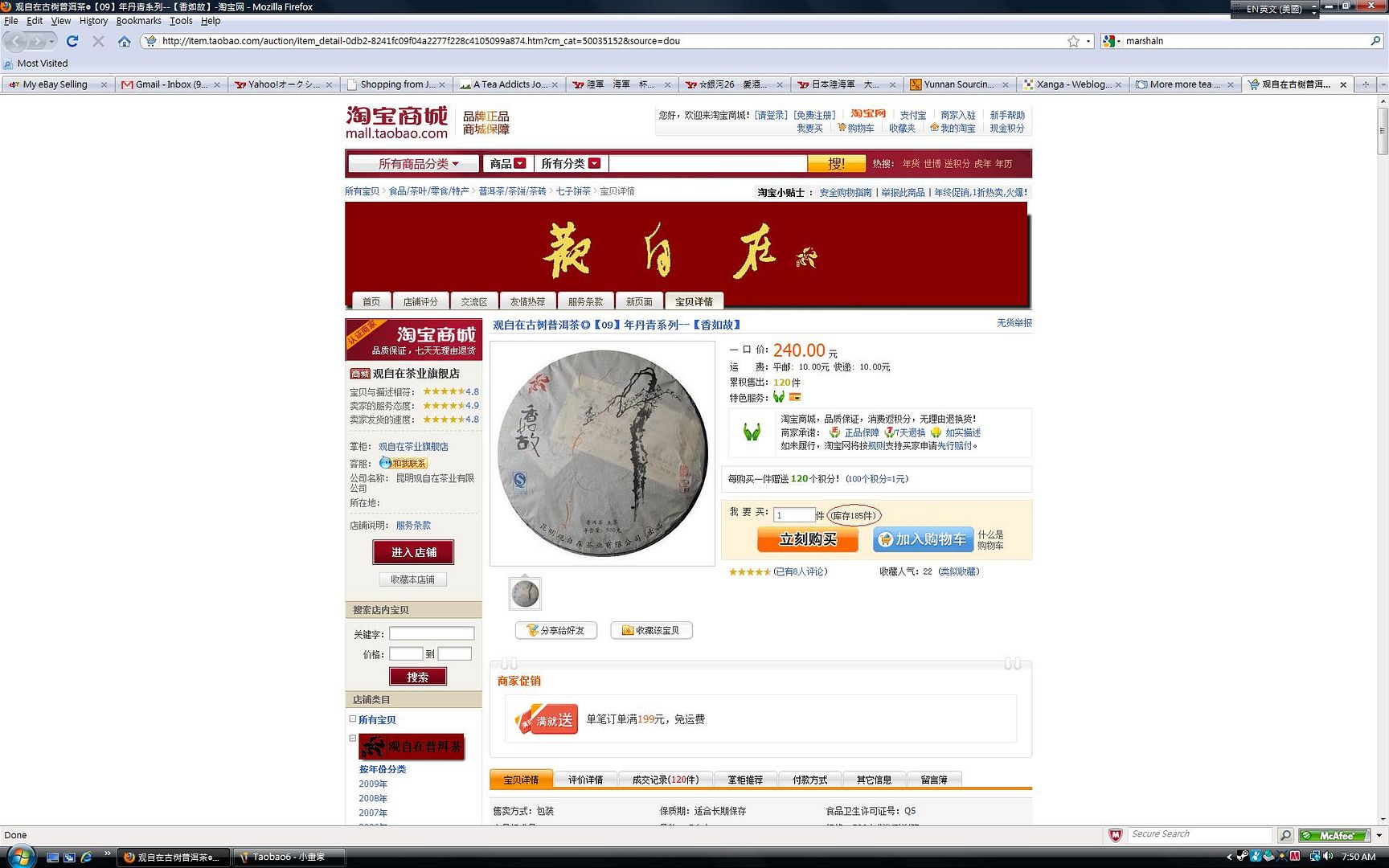

Now, since you’ll be using a proxy, you won’t be doing the actual bidding. However, right above the bid button is another piece of info that usually nobody will tell you about — the number of items remaining that this merchant has on hand. In this particular case, it’s 185. So you know that if you bought one cake, there’s more where this came from. This is actually somewhat useful, as sometimes they’re only selling one cake and one only, while others you can tell the seller has lots of it. If the proxy service you use is good, and you are buying in bulk, you can sometimes ask them if they have bulk pricing. Taobao merchants often do.

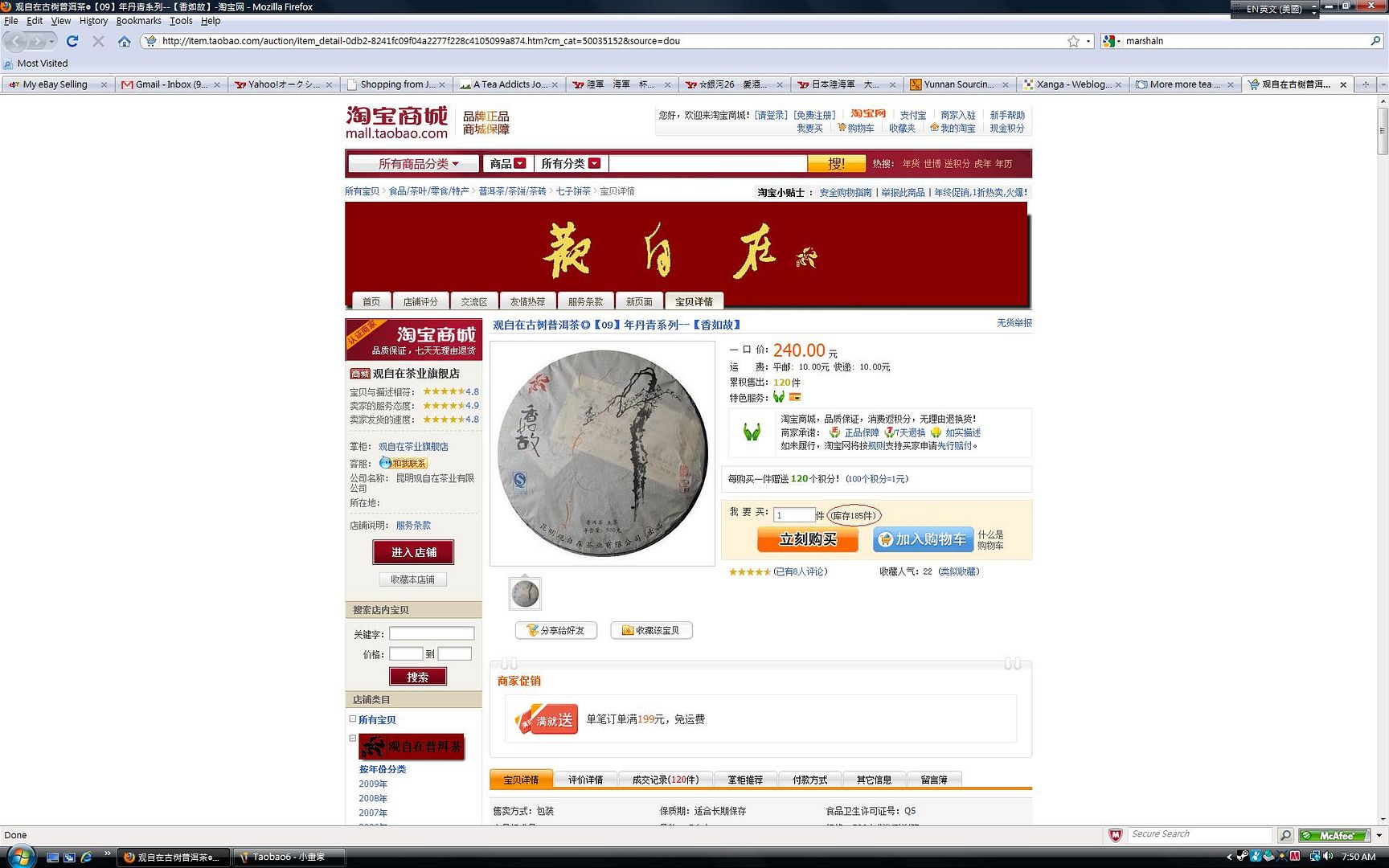

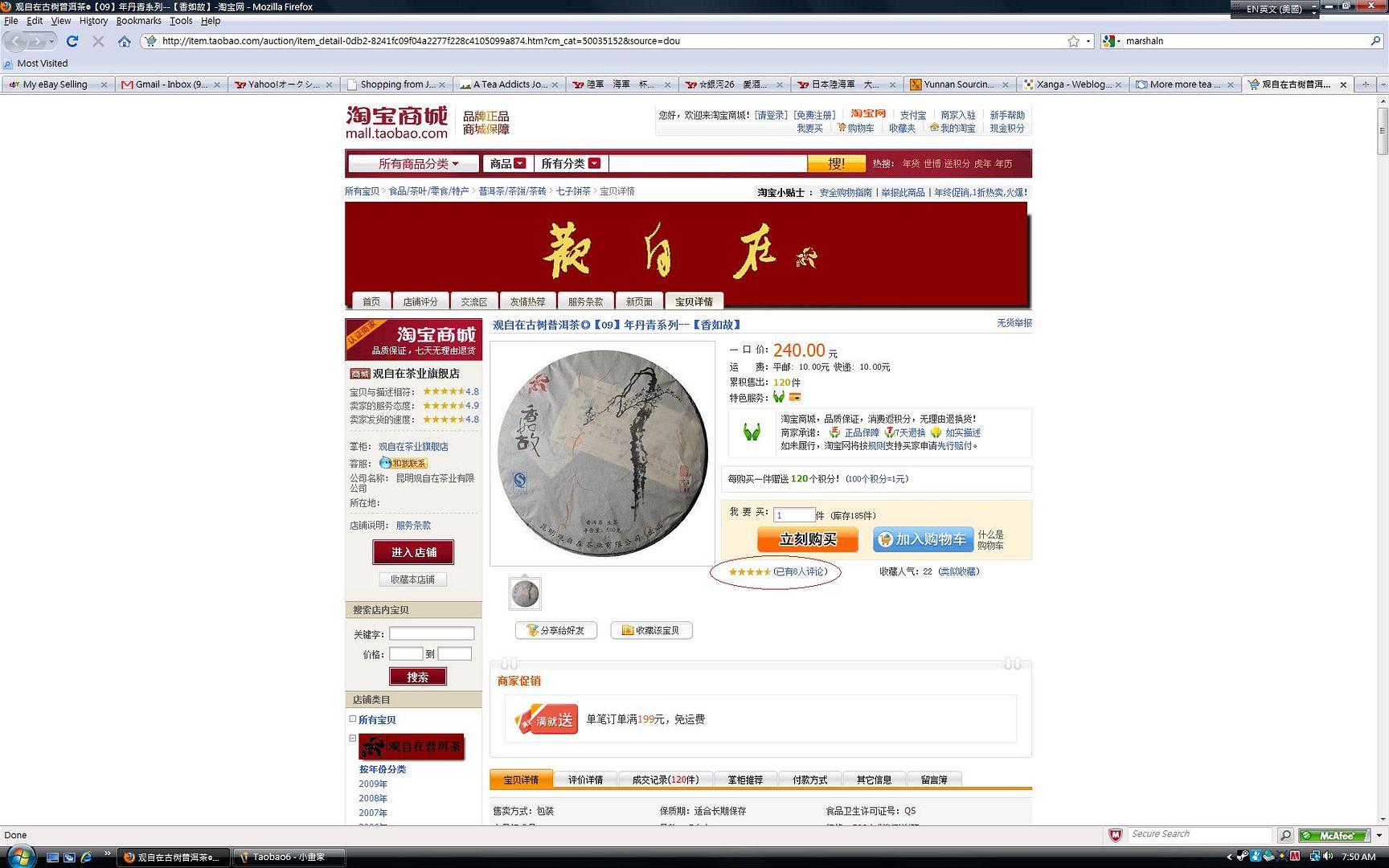

The third thing to look at, in this case, is a feedback on the specific item

The rating here is close to five stars, and 8 people have rated this item. If you can read Chinese, you can click on the link and read it all. Otherwise, it’s fairly useless.

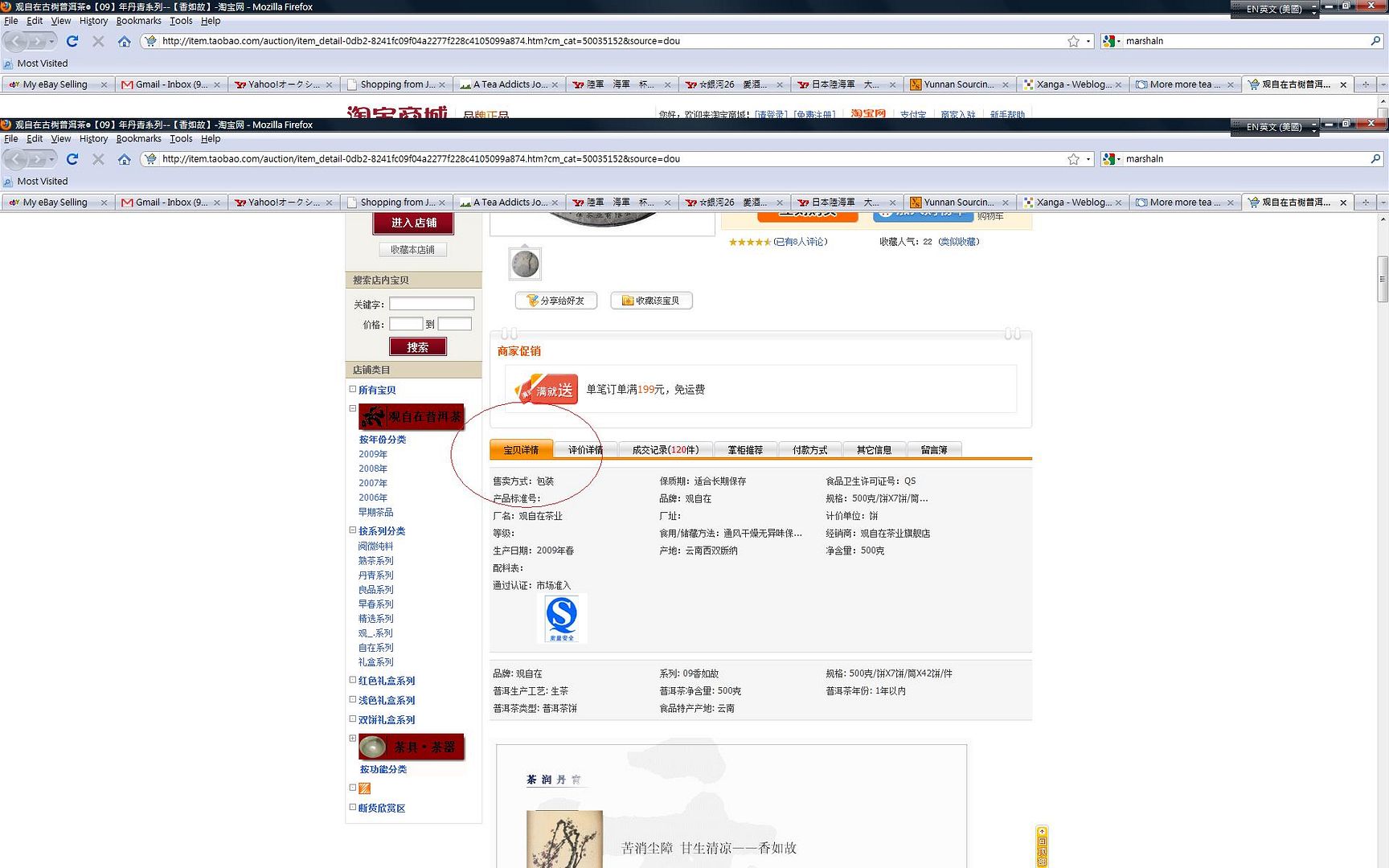

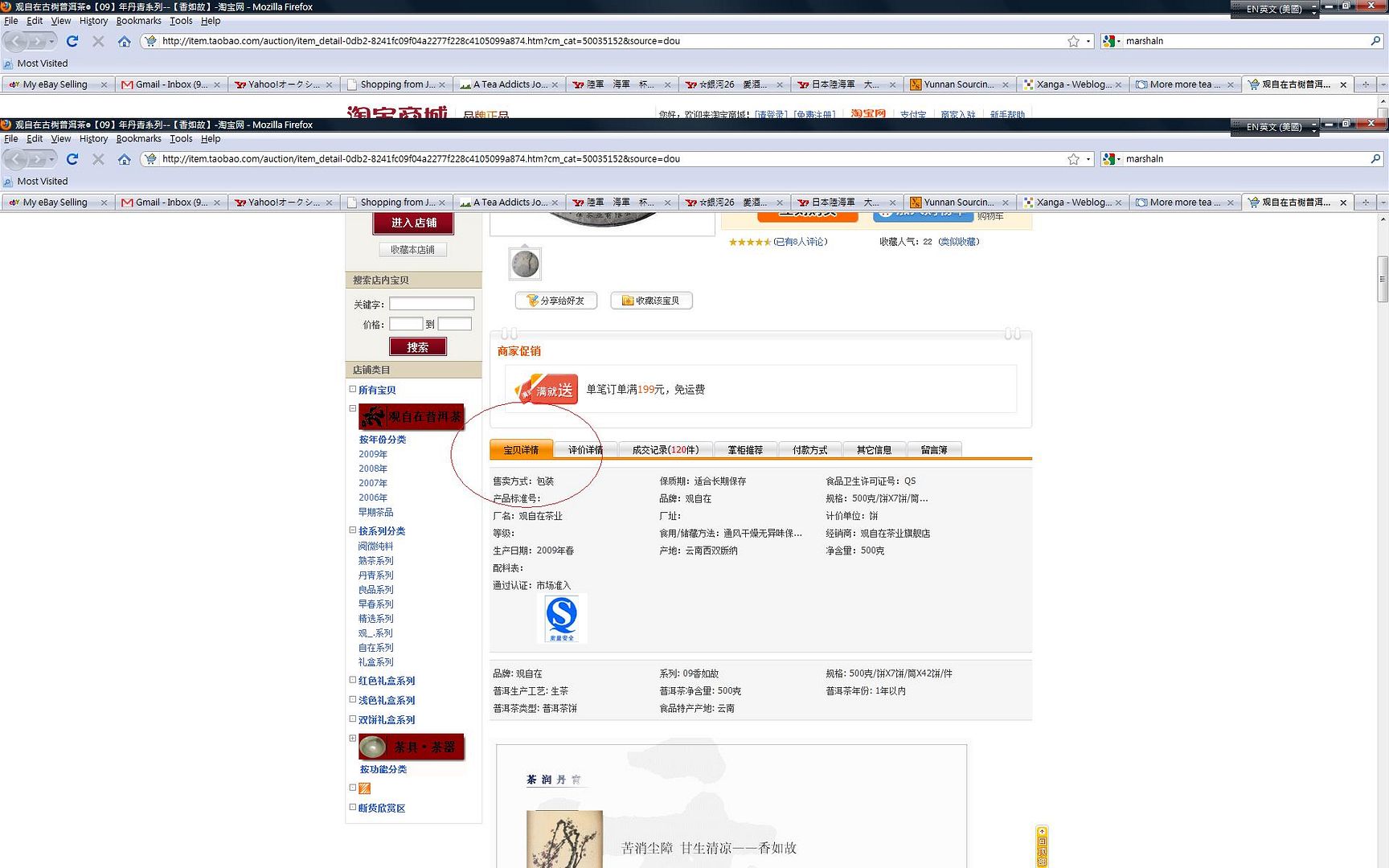

Now, for the actual item description:

Just make sure the first tab is the one highlighted, and if you keep scrolling down, you’ll see the item description, complete with pictures, all that. Often times the description that a seller posts is very generic and the only thing that matters at all is the pictures. The rest are all useless, repeated info. Sometimes you can try scanning the description for dates, but even then, they often don’t mean that much.

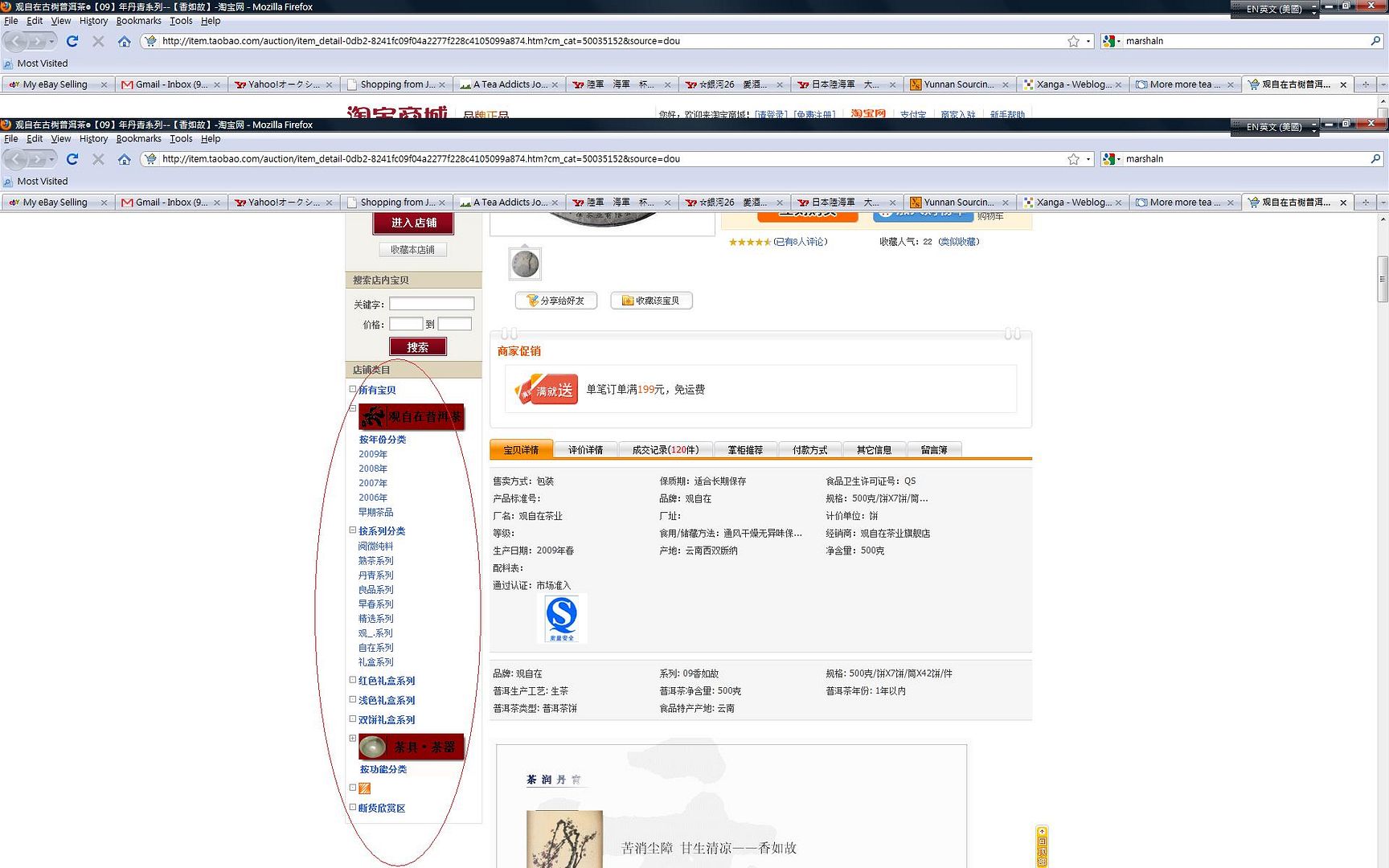

The sidebar on the left has other functions too, besides telling you the seller’s rating. If you looked at a cake and like the seller’s goods, you can click on one of the links on the left to go through a particular category of tea that the seller has. Oftentimes in a standard seller page, there’s a big orange button that links you to the whole store, but that’s not present here. That’s often a good way to browse for cakes, instead of searching for them. You can see how the seller has sorted them by year of production, and then by the different “series” that they have produced.

Now, some of you might recognize this cake and say “hey, I’ve seen this one before….” Yes, that’s correct, if you are one of those who hound sites that sell puerh, then you might have seen this cake from Yunnan Sourcing. This is the Guanzizai 09 Banzhang/Man’e cake, and if you look at the prices….

A comment on my last entry suggested that it’s not always cheaper to buy from Taobao, and this pretty much shows you why. The Taobao price for this cake is only marginally lower than YS’ price, but if you factor in the proxy fees and the potential for a higher shipping cost, then it’s really not a worthwhile venture. In general, I find Taobao to be good for things that one cannot find online, or can only find online at very inflated prices at certain vendors. Price comparison is always good, and it’s useful to do your homework. Most of the things I look for are not available online anyway, but when browsing, it’s good to check to make sure you got the right thing from the right place.

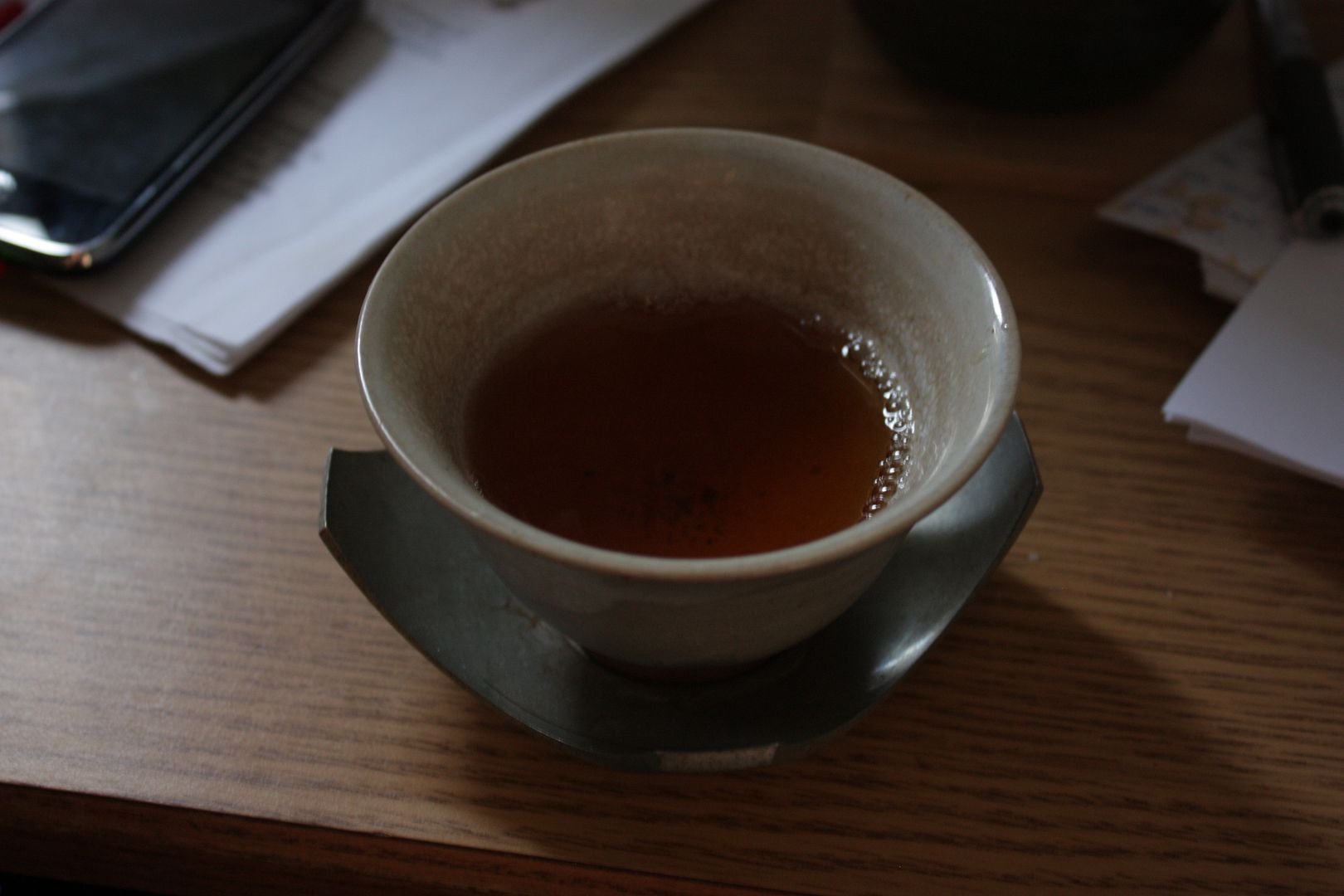

Now….. how do you pick cakes? Well, that’s a harder question to answer. Unfortunately, there are lots of cakes out there that look good in pictures but don’t taste very good, or have low potential. It often comes down to trial and error. There is also the possibility of fake tea, although that really has diminished over the years. I find that the most likely brands for fakes are still Dayi and Xiaguan, while the rest are either not expensive enough to be worth faking, or small enough so that nobody bothers. There are usually some signs that a tea is fake, starting from a “too good to be true” price. What I have done in the past is to buy one cake first from a vendor to make sure the cake is genuine or good, and then if I like it, I can always go back to buy more. This is where the “items remaining” number is handy. I have had some finds there, and also a few duds. In that sense, it’s not too different from the online tea buying experience in general. Look for good looking cakes, preferably with pictures of the liquor of the tea, as well as the brewed leaves. They all give you signs of what the tea is up to.

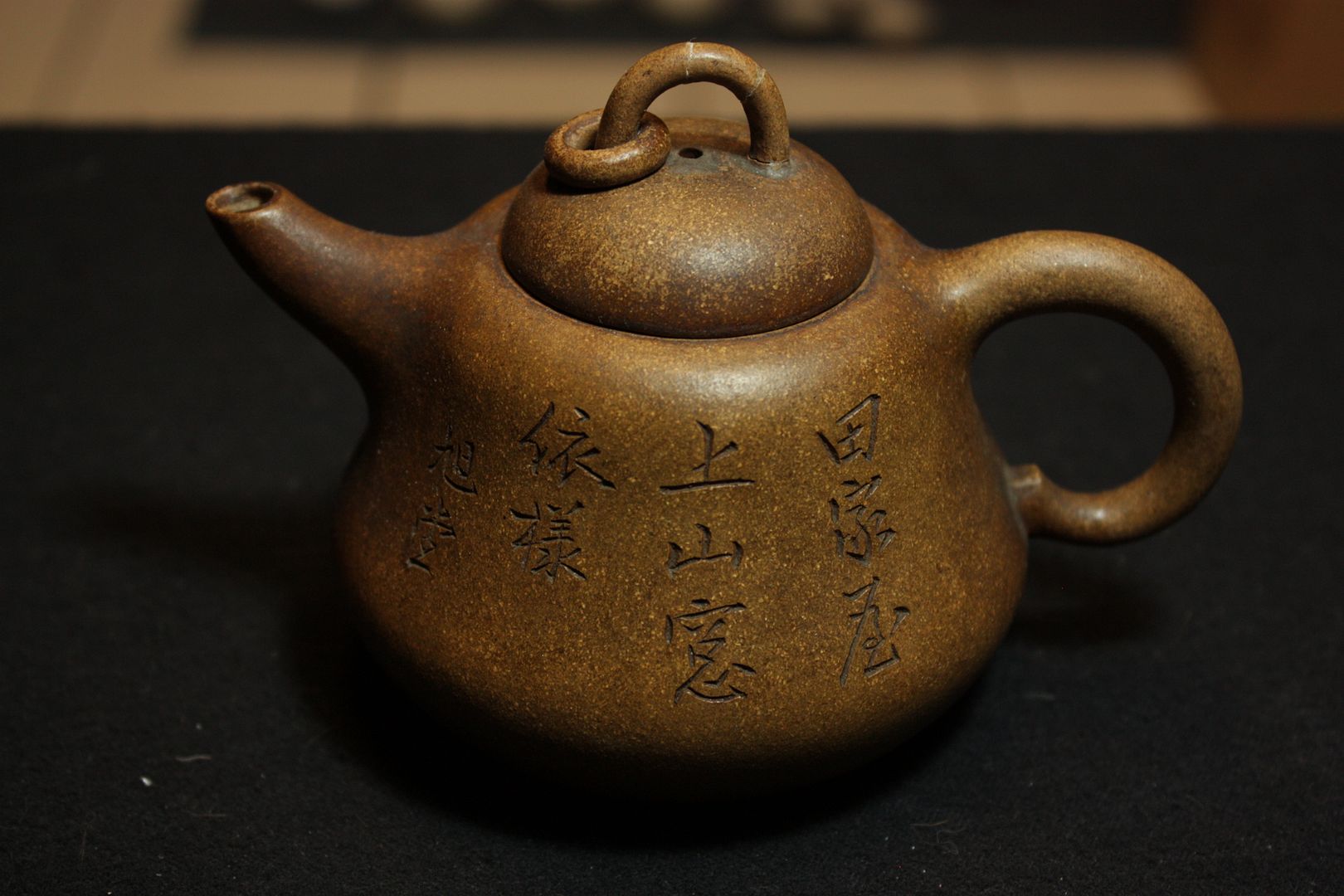

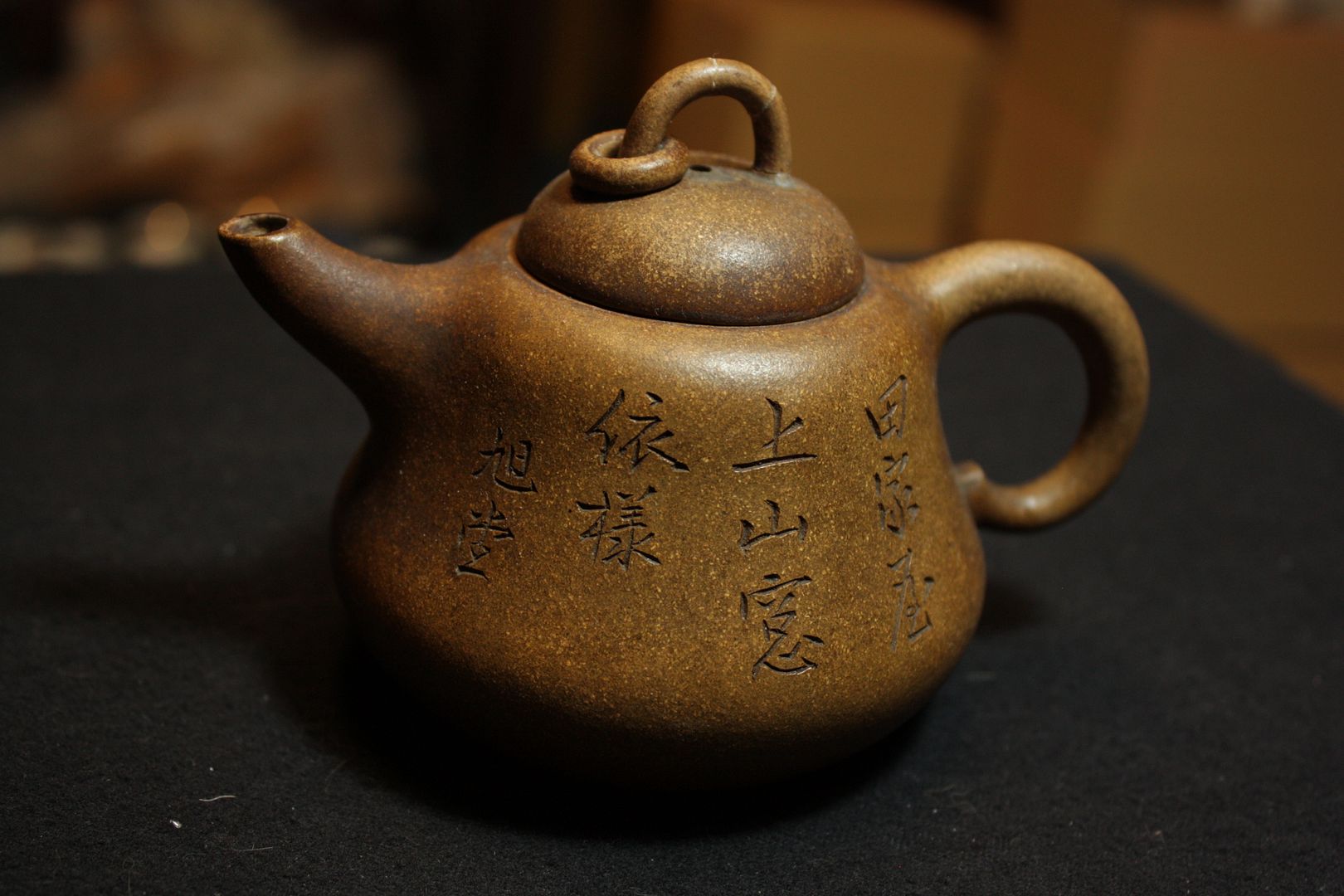

Maitre_tea also ask about buying Yixing on Taobao. I’ve looked at the selection, and I think I can say that if you’re looking for a new, modern piece, and if you are willing to take the risk, go ahead and give it a shot if the price is right. However, Yixing involves a lot more complexity, while puerh is more of a standardized product. I will avoid all claims of “antique” on Taobao, but as long as you know you’re buying a new piece and it’s advertised as such, it’s again not much different than buying online in general. In these cases, I would say that usually the merchants who seem to provide more pictures and information tend to be the better ones and will be more reliable. Good luck!

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

Interesting.... would 250C in my oven work?