*MarshalN: Last installment, see prior posts for what came before. This is the part where he talks about making tea. At the end he includes a few paragraphs from Ch’asu, but I will post those at some other opportune time. A reminder of the source of this:

Lin Yutang, The Importance of Living, 1937, New York: The John Day Company, pp. 221-31.

Usually a stove is set before a window, with good hard charcoal burning. A certain sense of importance invests the host, who fans the stove and watches the vapor coming out from the kettle. Methodically he arranges a small pot and four tiny cups, usually smaller than small coffee cups, in a tray. He sees that they are in order, moves the pewter-foil pot of tea leaves near the tray and keeps it in readiness, chatting along with his guests, but not so much that he forgets his duties. He turns round to look at the stove, and from the time the kettle begins to sing, he never leaves it, but continues to fan the fire harder than before. Perhaps he stops to take the lid off and look at the tiny bubbles, technically called “fish eyes” or “crab froth,” appearing on the bottom of the kettle, and puts the lid on again. This is the “first boil.” He listens carefully as the gentle singing increases in volume to that of a gurgle,” with small bubbles coming up the sides of the kettle, technically called the “second boil.” It is then that he watches most carefully the vapor emitted from the kettle spout, and just shortly before the “third boil” is reached, when the water is brought up to a full boil, “like billowing waves,” he takes the kettle from the fire and scalds the pot inside and out with the boiling water, immediately adds the proper quantity of leaves and makes the infusion. Tea of this kind, like the famous “Iron Goddess of Mercy,” drunk in Fukien, is made very thick. The small pot is barely enough to hold four demi-tasses and is filled one-third with leaves. As the quantity of leaves is large, the tea is immediately poured into the cups and immediately drunk. This finishes the pot, and the kettle, filled with fresh water, is put on the fire again, getting ready for the second pot. Strictly speaking, the second pot is regarded as the best; the first pot being compared to a girl of thirteen, the second compared to a girl of sweet sixteen, and the third regarded as a woman. Theoretically, the third infusion from the same leaves is disallowed by connoisseurs, but actually one does try to live on with the “woman.”

The above is a strict description of preparing a special kind of tea as I have seen it in my native province, an art generally unknown in North China. In China generally, tea pots used are much larger, and the ideal color of tea is a clear, pale, golden yellow, never dark red like English tea.

Of course, we are speaking of tea as drunk by connoisseurs and not as generally served among shopkeepers. No such nicety can be expected of general mankind or when tea is consumed by the gallon by all comers. That is why the author of Ch’asu, Hsü Ts’eshu, says, “When there is a big party, with visitors coming and coming, one can only exchange with them cups of wine, and among strangers who have just met or among common friends, one should serve only tea of the ordinary quality. Only when our intimate friends of the same temperament have arrived, and we are all happy, all brilliant in conversation and all able to lay aside the formalities, then may we ask the boy servant to build a fire and draw water, and decide the number of stoves and cups to be used in accordance with the company present.” It is of this state of things that the author of Ch’achich says, “We are sitting at night in a mountain lodge, and are boiling tea with water from a mountain spring. When the fire attacks the water, we begin to hear a sound similar to the singing of the wind among pine trees. We pour the tea into a cup, and the gentle glow of its light plays around the place. The pleasure of such a moment cannot be shared with vulgar people.”

In a true tea lover, the pleasure of handling all the paraphernalia is such that it is enjoyed for its own sake, as in the case of Ts’ai Hsiang, who in his old age was not able to drink, but kept on enjoying the preparation of tea as a daily habit. There was also another scholar, by the name of Chou Wenfu, who prepared and drank tea six times daily at definite hours from dawn to evening, and who loved his pot so much that he had it buried with him when he died.

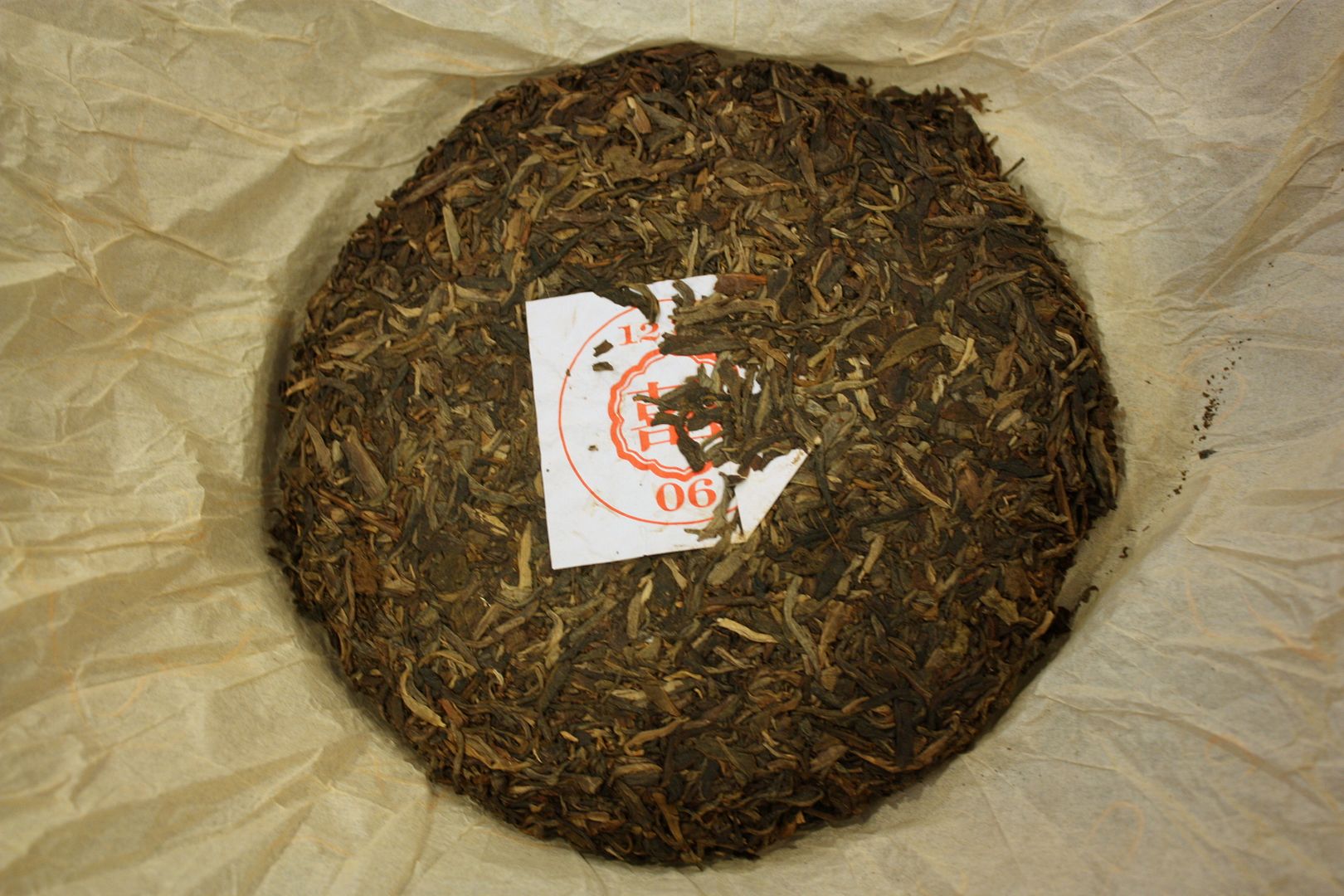

The art and technique of tea enjoyment, then, consists of the following: first, tea, being most susceptible to contamination of flavors, must be handled throughout with the utmost cleanliness and kept apart from wine, incense, and other smelly substances and people handling such substances. Second, it must be kept in a cool, dry place, and during moist seasons, a reasonable quantity for use must be kept in special small pots, best made of pewter-foil, while the reserve in the big pots is not opened except when necessary, and if a collection gets moldy, it should be submitted to a gentle roasting over a slow fire, uncovered and constantly fanning, so as to prevent the leaves from turning yellow or becoming discolored. Third, half of the art of making tea lies in getting good water with a keen edge; mountain spring water comes first, river water second, and well water third; water from the tap, if coming from dams, being essentially mountain and satisfactory. Fourth, for the appreciation of rare cups, one must have quiet friends and not too many of them at one time. Fifth, the proper color of tea in general is a pale golden yellow, and all dark red tea must be taken with milk or lemon or peppermint, or anything to cover up its awful sharp taste. Sixth, the best tea has a “return flavor” (hueiwei), which is felt about half a minute after drinking and after its chemical elements have had time to act on the salivary glands. Seven, tea must be freshly made and drunk immediately, and if good tea is expected, it should not be allowed to stand in the pot for too long, when the infusion has gone too far. Eight, it must be made with water just brought up to a boil. Nine, all adulterants are taboo, although individual differences may be allowed for people who prefer a slight mixture of some foreign flavor (e.g., jasmine, or cassia). Eleven, the flavor expected of the best tea is the delicate flavor of “baby’s flesh.”

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

Interesting.... would 250C in my oven work?