Now if only I had a setup like this. This is a sitting area for guests who are coming in to soak at the onsen and resting up before they leave. The water is kept warm all day long with a slow charcoal fire going under it. It’s nice and warming to just sit there.

Now if only I had a setup like this. This is a sitting area for guests who are coming in to soak at the onsen and resting up before they leave. The water is kept warm all day long with a slow charcoal fire going under it. It’s nice and warming to just sit there.

Entries tagged as ‘tetsubin’

This is how you use a tetsubin

November 3, 2013 · 14 Comments

Buying tetsubins

November 4, 2012 · 19 Comments

Buying tetsubins is a treacherous business. There are all kinds of problems that can arise in the process. I’ve probably bought about a dozen of them now, over the past few years, so have a reasonable sample size to talk about. The first issue, when buying them used anyway, is that the pictures are not always clear, so you are taking a gamble, and the size of your gamble depends largely on the quality of the pictures.

The first tetsubin I ever bought was a cheap little hobnail thing that I bought off eBay for about $20. It was cheap, it was small, but it was a tester, so to speak. At that point I didn’t own a tetsubin, and wasn’t sure of its usefulness in tea brewing. When it came, it had issues – specifically, the water tasted funny. It was sweet and yellow, and I think it was tea residue. The previous owner used it as a teapot (or something similar) and the water therefore was infused with whatever leftover flavours in the tetsubin. I eventually treated it by baking it in the oven – all the volatiles got burned out. I also discovered, while baking it, that the surface was covered in some kind of gunk – a layer of substance that I’m not sure what it is, to this day. Some of it might have been the paint/coating on the surface to keep it from rusting, but something else was there too – something that melts a little at low heat and was sticky when touched. It all got baked away, which was a good thing. Still, it was too small to be practical, but as a proof-of-concept, it worked, so I resold it on eBay for the same price I bought it for, and moved on.

The second was also an eBay purchase, the one right next to the hobnail one in the above-linked post, in fact. That one had a major problem – a tiny little hole, to be exact, that was right in the center of the bottom of the tetsubin. It was tiny, so not visible in any pictures, and it wasn’t pointed out in the listing, but it was there, and it rendered the pot unuseable. That was a pain, and another way that a purchase can go wrong.

I’ve had a number of good purchases since then, and in fact, the third tetsubin I ever bought is also the one I still use most days. It works – it’s lighter, relatively rust free (although more rusty now than when I bought it) and it’s good to look at. Still, there have been issues in the ones I’ve bought since. Sometimes, they’re so rusty as to make the tetsubin hard to use – it’s a real pain to clean, and an investment of time. Sometimes, the sizes are not clearly marked, so when they show up, it’s a real surprise – not always a pleasant one. Other times, there have been repairs done that wasn’t mentioned, and while it might still be usable, it’s good to know if your tetsubin has been fixed or not.

A recent acquisition was a bit of a gamble – the interior shots were iffy, and so I wasn’t sure what to expect. Thankfully, it turned out all right.

A bit rusty inside, but that’s solvable.

Which gets to the other major problem with these things these days – price. Whereas a few years ago, tetsubins were relatively cheap affair, that’s no longer the case. These days anything half decent is at least a few hundred dollars, and anything with any amount of decoration will set you back way more. Trying to find those bargains are hard now, and trying to find bargains in good condition, more difficult still. This is mostly driven, like everything else, by Chinese demand – a tetsubin like this can easily sell for 10,000 RMB in China, advertised as an antique of some sort. It is indeed good for boiling water in, but those prices are ridiculous. Alas, that’s the reality we live in these days, just like the prices for tea.

Silver revelation

February 8, 2011 · 3 Comments

Today I drank a sample that I got recently, without any real labels or anything. All I can remember (and discern) is that it’s some sort of an aged oolong — not really aged, just a few years under its belt, with a little sourness in the smell and that characteristic aged smell. I brewed it up normally, did not think much of it — seems a little hollow, and one note, but not particularly interesting. I brewed two kettle worth of water with it, and decided to basically call it a day.

Then, late night, I thought I wanted some more tea, but adhering to my one-tea-a-day rule, I had to just boil more water for my tea, instead of using new leaves. For some reason, I picked up my silver kettle instead of my usual tetsubin for the water. In the water goes, out comes the tea…. and the tea seems to have gained new life. All of a sudden, the taste is richer, with a fuller body and a deeper penetration into the back of the mouth and the throat area. The high note, which was already present in the original brewing, is now really obvious, but has undertones to support it so that the tea is not bland and hollow anymore. All in all, the tea is now good, and I want more.

This of course confirms what I already know, but sometimes forget – silver tends to be better for the teas with lighter notes. Sometimes, when faced with teas like aged oolongs, it’s not always easy to tell what’s going to happen, and experimentation is necessary. Now I wonder if I should go back and test some other recent teas with the silver kettle, which, until today, has been neglected in the back of my teaware cabinets. I think it’s time to work on water again.

Categories: Information · Teas

Tagged: silver, tetsubin, water

Charcoal boiling

September 22, 2009 · 7 Comments

I tried out my brazier today, outdoors, with charcoal. The result, I must say, is mixed. It took a long time for the water to boil. I think at first I didn’t add enough charcoal. Then, it was the relatively cool temperature keeping things slow. Then, there’s the issue of making sure the heat is funneling up to the kettle and not dispersing on to the sides, since I have a large-ish brazier. Originally, I wanted to use it to boil water for a class on Thursday, but perhaps, I would have to resort to using an electric kettle to boil the water and then just use the charcoal to keep the water warm…..

Sigh, compromises. I think the cold air really makes a huge difference to how long it takes to boil. I remember even using my heating plate outside, it takes a lot longer to boil a kettle than inside. These are the little things that reminds you how making tea in the old days took considerably more effort than it does today.

Categories: Objects · Old Xanga posts

Tagged: Japanese tea, teaware, tetsubin

The Demon Revealing Mirror

June 30, 2009 · 12 Comments

The Demon Revealing Mirror is one of those somewhat mythical and fantastical items in Chinese lore that supposedly will show who (or what) is a demon and who is really a human. You just shine the mirror on the object, and you’ll get your answer.

A friend of mine in China who presses his own cakes has likened a good silver kettle to one of these mirrors, and I must say I agree. I’ve been experimenting with my kettle the past few days with different teas, and comparing to what I think of the teas using the tetsubin, and I think one thing is clear, and that is how different they taste with the two kettles.

The two teas I’ve tried recently are both 2006 Yiwu, one being a fall tea that this friend pressed, and another being the 2006 spring Douji Yiwu. When I drank them with the tetsubin, the fall Yiwu tastes a bit flat and boring — rather unremarkable, in fact. The Douji, on the other hand, was quite nice.

All changed, however, with the silver kettle. The fall tea was very fragrant and strong. The Douji, on the other hand, turned out a little bitter and rough.

What to make of this?

Well, I think the silver kettle does a good job of telling you what the tea is like and highlighting the fragrant notes, while tetsubins are often softening — they round out the rough edges of the teas, and adding to the body of the tea. In this case, I think that’s exactly what happened — the Douji was rounded out by the tetsubin so that the bitterness and the roughness were subdued, leading to a rather pleasant drink, while the fall tea gets a little more subdued. Since it has few low notes to speak of, it doesn’t get much benefit from the tetsubin.

I’d hesitate to say that the silver kettle is more honest — highlighting the fragrant notes is not any more honest than smoothing out rough edges — but it does present a very different side of the tea. Here are some spent leaves for you to look at.

Categories: Objects · Old Xanga posts

Tagged: silver, teaware, tetsubin

Changing tastes

June 24, 2009 · 9 Comments

I rarely repeat the same tea two days in a row, and never with the same teaware. I think one of the joys of drinking tea is to thoroughly explore all the varieties that it offers, be it young, old, roasted, green, black. Add in the variety that you get with changing teaware, and the combinations are endless.

Weather was nice today after a nasty week of rain, so I decided to drink out on the balcony while my cats decide to soak up some sun. Rather than using my usual tetsubins, I opted for one of my silver kettles instead

This is something I found on Ebay, of all places, for a rather reasonable price. It’s Korean in origin, and on one side is inscribed the words “For Mr. and Mrs. Henderson”. I’m pretty sure originally it was intended for use as a teapot, but it’s very large for a teapot, and I’d rather use it as a kettle, which is exactly what I did.

Water from silver kettles tend to accentuate the high notes in a tea. With good tea, the aroma will coat your mouth and linger for a long time. What it won’t do is to add to the body, and if the tea is sour, it may make that show up more prominently as well. So, whether it is really a good idea to use a silver kettle for the particular type of tea you’re drinking really depends. I don’t think silver kettles should be used universally for all teas. Tetsubins are much more versatile, I think.

The first tea I had today was an aged shuixian that I bought in Beijing almost three years ago.

It tasted very different from the last time when I made it a few weeks ago, using my usual tetsubin. I think I actually prefer this tea with the tetsubin — the water from a tetsubin accentuates the qualitites of this tea. It’s not the highest grade of shuixian, just some common stuff, and perhaps it only deserves the commoner treatment.

The pot I used still baffles me though. For those of you familiar with bankoyaki, it might look awfully like one, and I still don’t know if this is actually a Yixing pot or not. Although the seal says “Yixing County Mengchan Made”, I have my doubts as to its geographical origin. Maybe the potters out there can tell me if this looks like a thrown pot or a hand built one.

Not quite having enough tea, I had another, this time an aged oolong from Taiwan that I recently acquired. It’s nice and mellow, but works much better with the silver kettle. All in all, a pretty good day for tea.

Categories: Objects · Old Xanga posts

Tagged: aged oolong, silver, teaware, tetsubin, yixing

Caring for a tetsubin

July 7, 2008 · 3 Comments

One of the tetsubins I have came with its original box, and inside the box are two inserts. One is a list of the artist’s achievements — awards, shows, etc that he has been in (among which was apparently a purchase by the emperor!). The other, though, is rather interesting and which I neglected to read when I got it — it’s about caring for the tetsubin.

The first part of it is rather simple and not worth mentioning, but the last part has four points, which are rather interesting

1) Use pure water, rather than tap water. If you have to use tap water, then you should let it sit for a night before using it — and only skim off the top, not the whole container. The bad stuff, such as whatever chlorine or anything else they use, will sink to the bottom, so they say

2) Use a mild heat to dry the thing out thoroughly after use, and let it sit uncovered for the night so that it doesn’t trap moisture inside. That’s sensible.

3) Use a cotton cloth that’s slightly damp to wipe the outside of the kettle after use, while it’s still warm. That I didn’t think about at all

4) Never use it on a gas stove, it’ll crack the damn thing.

I wonder what the damp cloth will do. Maybe I should try doing that from now on.

Categories: Information · Objects · Old Xanga posts

Tagged: skills, teaware, tetsubin

On silver kettles

June 25, 2008 · 10 Comments

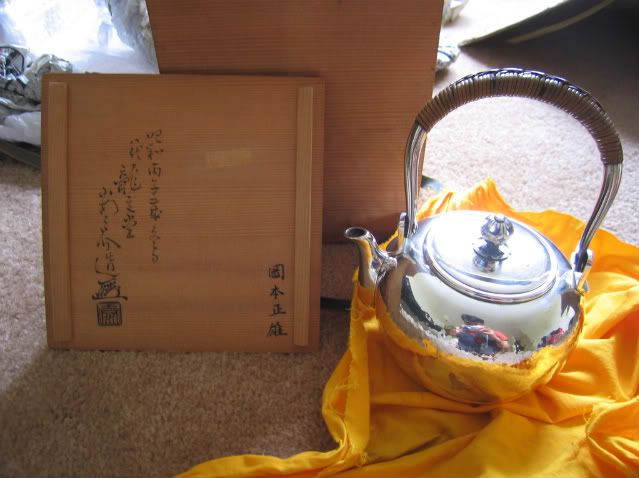

This thing just came in the mail. No, it’s not mine (I wish!). But I do get the privilege of playing with it and using it for a little bit before handing it off to the friend whom I helped source this item. You can see my reflection in the kettle :).

Since there’s very little literature out there on these things, I figured I should tell you all what I have learned so far. Silver kettles come in different shapes and sizes. The small ones are very thin and were more like teapots than kettles — they often have an internal filter, and have an engraved surface with a flower or some other motif. Those are the cheapest and really not meant for water boiling. Then you have the medium sized ones like this one, which are good enough sized for brewing purposes. Compare:

And my tetsubin is fairly large. To give you a better idea, from the tip of the spout to the other end, it’s about 6 inches or about 15.5cm. The seller said this weighs 570g including everything. Then you have the large ones — the largest ones I’ve seen are around 1100g in weight and correspondingly larger in size. It’s pretty heavy, and a lot of silver. Obviously, you have to pay more for those, but even those ones should be obtainable for under $1600 or so unless it’s extremely intricately decorated or special in some other way (famous person, etc..).

A really important thing with all Japanese wares that are of some age though is the box — as you can see in the first picture, the box has stuff written on it. Here, it had a date — winter 1936 (written as Showa “bingzi” using the old Chinese 60 years cycle system). That’s more than 70 years ago. The thing also says “8th generation Ryubundo”, and then a name, “made by”, and then a Japanese style signature and a seal. The name is probably that of the person who is the person holding the firm “Ryubundo”, a fairly famous metalworks maker (best known among aficiandos for their tetsubins probably). So, this is probably made by that guy — not a bad pedigree. The name on the bottom right was probably the owner of the kettle. Sometimes boxes also come with some insert — a printed name card or piece of paper that basically advertise the shop’s wares, but the important info is always what’s on the box itself, usually the lid and sometimes the bottom of the box. But wait — look at the exterior of the lid, and it says “Precious Pearl shaped Tetsubin”. Hmmm, tetsubin?

The box (and the yellow cloth) are both part of the packaging, and having the original (rather than just any random box for something else) can significantly change the value of the item — usually for the higher. Unfortunately, this kettle didn’t come with the original box, but for less than 3x the price of the silver it took to make the kettle at today’s crazy prices, one can hardly complain. This actually happens a lot, as I’ve bought a bowl or some other stuff that obviously didn’t have the original box but instead came in what fit. Still, having A box is handy — not least because it offers quite a bit of protection.

Then there are the details — like whether or not something is “pure silver”. From what I understand, the “jungin” stamp on silver items worked sort of like “sterling silver” stamps on western silver items — it’s not quite “pure”, but pure enough. And…. if something doesn’t have it, chances are it’s not actually “pure silver” — if you made the item with high purity silver, you’d want the people buying it to know. To do otherwise would be, well, stupid. Silver alloys are not bad, but with lower purity — it should command a lower price. The Japanese “jungin” seal is a tiny little thing, usually in the center of the kettle’s bottom — 4mm by 2mm, very small.

I think those are all the things to really look out for in a silver kettle. The rest are intuitive — is it well made? How was it made? This one you can see little hammer marks on it — a deliberate design decision. Some have hobnails. Others are more unique — swirls, etc. Once I saw one that was absolutely gorgeous, with a jade ball as a handle for the lid, and a very unique design. I still wonder why I didn’t jump on that thing.

How does it work for tea though?

I gave it a try today, although I don’t want to be too conclusive without more tries with it. Drinking the same tea as I did the last two days, I think I can say the tea came out a little more contemplative — there’s definitely an extra dimention in the tea that I haven’t tasted before, and that it gave the tea a very deep throatiness that lasted quite a long time. That itself was rather impressive. I am going to play with it tomorrow with another tea — a lighter fare, perhaps, to see how it goes.

Categories: Objects · Old Xanga posts

Tagged: silver, teaware, tetsubin

Seasoning a tetsubin

June 2, 2008 · 3 Comments

The other thing that I discovered yesterday was by accident. We were making a red bean paste dessert for the guests, and when it boiled, it boiled over a little bit and spilled some onto the range. I didn’t think much of it, and when I went to heat up some more water as our first pot ran out, I put my tetsubin on the same range and started heating it.

It caught on fire, since there was some red bean paste on the bottom.

That, however, turned out to be a sort of blessing, for I finally found out how some of the other tetsubins I’ve seen get that old, black sheen — I think it’s from smoke and deposits on it, or some such. Maybe it’s also just the seasoning from putting some oil on it and then firing it, but it seems like good old smoke will do the trick on its own (or am I wrong?). My tetsubin, in some of the places where there was that fire, now has a bit of a black sheen to it whereas the other parts are still brown as before.

Now I am thinking…. a brazier might be in order….

Oh boy, the list of stuff to get is, indeed, endless

Categories: Objects · Old Xanga posts

Tagged: teaware, tetsubin

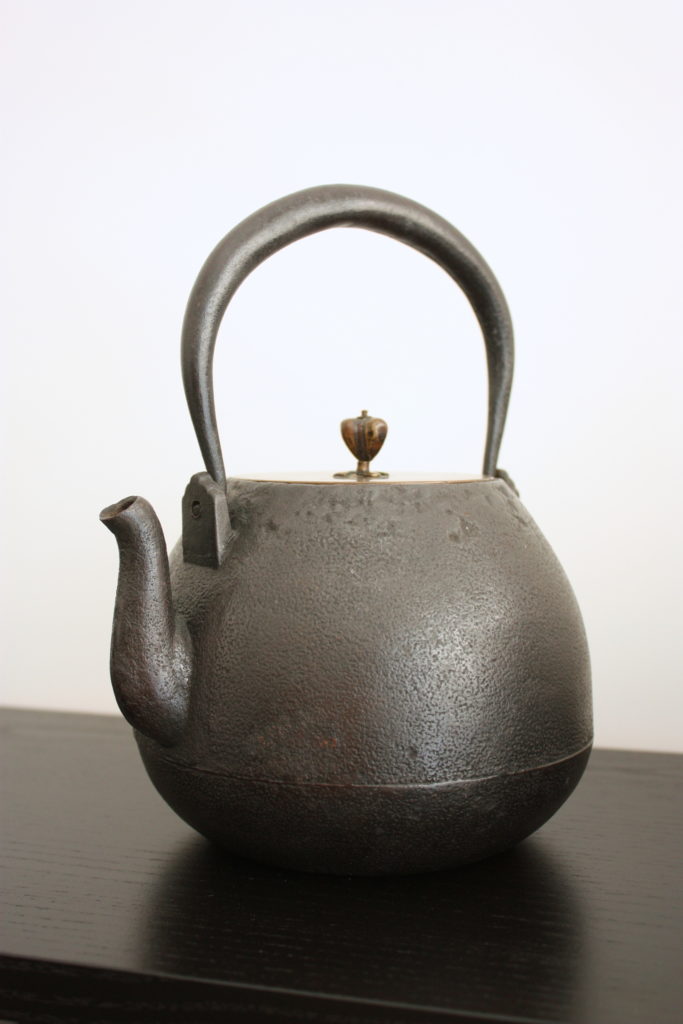

Telling tetsubins apart

May 18, 2008 · 18 Comments

Tetsubins come in all shapes and sizes. Here are three that I own, as well as the smaller, flatter hobnail one that I had trouble with trying to de-smell. Since switching to it, I’ve found it does help with the tea I brew — it’s gained a bit of a deeper flavour, and is probably especially suited to the types of tea I normally drink, which is mainly aged teas these days. It also gives Wuyi teas a nice aftertaste that is more pronounced than with my Braun kettle.

As you can see… they’re not the same at all.

I think when picking out a tetsubin, there are a few things to keep in mind, aside from the obvious question of cost. First — is it a used item or is it new? New ones tend to have enamel lining inside, which neutralizes any effect it might have on your water. The enamel will break off eventually, especially if you heat the pot on the stove directly. If it’s used — how much rust is there in the pot? Does it leak? When I bought my leftmost pot, that was the problem — there was a hole in it and it leaks. Then, I got the rightmost one, which was a newer make, and lightly used. A bit of rust (I’ve since added to it a little — iron will rust no matter what you do), but nothing problematic and makes nice water. Then, very recently, I acquired the middle one for a very low price (around $50). It’s a heavily used item, also not very well kept, thus the outer surface is rusty. You can see it clearly here

Not the prettiest, but I liked the shape of the thing. I also liked the minor details

Generally speaking, after having looked through many, many of these online, I’ve noted that the cheaper ones are the ones with the solid iron lids — lids that are made of the same cast iron as the kettle itself. Better ones will invariably have other kinds of lids, made of some sort of copper alloy usually, but very rarely also of silver (which sends the price of the tetsubin skyrocketing). Under the lid is sometimes written the name of the maker

In this case Ryubundo, a famous and also very prolific tetsubin maker that, I believe, got started in the Meiji period. They’re still making tetsubins today, I think, and although well known and famous, Ryubundo tetsubins are actually quite common — you can easily find one from Japan if you look. However, I’ve seen places that sell just lids for tetsubins by the dozen — of various kinds, usually, I’d imagine, from old rusted and broken tetsubins. The lids, however, are worth money, and a non-famous maker tetsubin can be made into something else with the addition of a nice (and hopefully fitting) lid.

I think my right hand one, i.e. the most often used one, is of the usual simple design — a plain pattern with some sort of uniform surface. These are quite common, and generally cheaper, especially if there’s no maker’s name, but even if there are they don’t exceed maybe $200 or so in price. The ones that are wholly iron are even cheaper.

Then, however, you get into more expensive territory when they start having designs on them. The left hand one is of a simpler form — some sort of relief pattern of whatever it is — ranging from animals to leaves to geometric patterns to flowers to VERY elaborate relief patterns of houses, rocks, etc. Some are tasteful, others are gaudy. Some also have old kamon, or family crests, of important families. Those can be quite nice and rustic, but those also tend to be expensive. Of course, these things depend on individual taste.

It’s worth keeping an eye out for the way the handle is made too — sometimes the handles are also elaborately designed, whether with some inlaid patterns, as my middle one does (though much faded), or in some cases, with detailed sculpted patterns and figures. Both the patterns on the handles and on the body itself can be highly decorative and sometimes made of other precious metals, usually silver, sometimes gold. Those, again, will drive the price of the items up into the stratosphere.

I sometimes see these tetsubins having a very shiny black surface with zero rust, which I find incredible because if you use it, it’s going to rust, in and out (slight rusting on the outside is hard to avoid when it deals with water all the time). So my guess is, they somehow rub it off or polish it with something, although I don’t know what. If anybody does know, please let me know 🙂

Find ones with original boxes — and make sure (if you can read Japanese — or ask friends who do) they’re the original, not some substitute. Of course, that’s not always possible, and if you just want function, ones without the original wood box work just as well, but the wood box cost money, and the value of your item is substantially lower to collectors if there’s no box that comes with it. My “new” one comes with a very nice weathered box. I don’t think it’s the original, but I wasn’t about to complain for the price I paid, flawed though the piece may be. The box, if nothing else, gives the item an extra air of history to it. I’m a sucker for those things.

Tetsubins are by no means rare, since the Japanese seemed to have produced them in prodigious quantities. A search on Trocadero will yield a number of fine ones, some of which I personally think are fairly reasonably priced (for the quality, anyway). One downside to these things — they’re heavy, so I think I’ll be capping my purchase of these things for now until I don’t have to move again any time soon, because otherwise, it’ll be hell to move.

Categories: Objects · Old Xanga posts

Tagged: teaware, tetsubin

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

I took you at your suggestion and have been reading some of your old post-Covid posts. I haven’t been to…