A few people recently pointed me to a blog post on McIntosh Tea serving as a “how-to” guide to storage for puerh. I think it is always good to have more discussion on this topic, and very often people have little idea of what to do for teas in general, and puerh in particular. However, I also believe it is very essential to have good, accurate information, and when things pop up online or elsewhere that seem to be misinformed, it can easily mislead people in the wrong direction. Alas, I think there are a number of problems in this post that need to be questioned.

The premise of the post is that Mr. McIntosh is trying to build a tea storage for his budding business as well as personal collection, which is a great reason to figure out a good way to store your tea. However, after talking to “tea wholesalers, retailers, collectors and experts in the field”, the solution he came up with is more or less the same as a lot of what others have built that are affectionately called “pumidors”. Basically – a closet, or an enclosed space, with a water source that provides some additional humidity in the environment. So far, so logical.

This is where the problems start. There are logistical issues, such as having a wet towel constantly on a plaster wall being VERY likely to induce mildew in that particular area of the wall (and thus more likely to infect the tea stored in the same space). The entire post is built on a foundation that is really rather shaky, namely that of focusing overly much on relative humidity and not enough on anything else.

The most important of these factors is temperature. Relative humidity of 70% in a 25C environment is very different from the same relative humidity in a 15C environment. The former is conducive to tea aging, the latter is not, because it’s too cold. Aging tea requires humidity and temperature, neither of which can be too low. Ignoring temperature from the equation is basically like telling people to store wine correctly on a rack in a damp environment, while forgetting to mention it needs to be kept cool. You can end up with vinegar that way.

Also, the relative humidity number used in the post is itself rather problematic. How did he come up with 50-65% as the optimal range for such storage? I can’t quite figure it out, and would appreciate if he would elaborate. After all, Kunming, which is well known as a place with relatively dry storage condition for puerh, has humidity that fluctuates between 60-80% throughout the year. 50-65% is considerably lower, and if you believe anything Cloud says, he would think that’s too low for the right conditions for aging good puerh tea, and 20-30C being a good range of temperature.

This choice of super-low relative humidity is probably explained by McIntosh’s self-professed dislike of “wet-stored tea”, but as I have made clear many times before, “traditional storage” is not the same thing as “wet storage”. You cannot replicate traditional storage at home, even if you try and pump up humidity and temperature. What you’ll get instead is some nasty tasting, mold covered tea, but the richness and the flavours that at least some find alluring in traditionally stored teas will be missing. For that, you need large volume, expert control, and the proper environment for it. You won’t get that at home, even if you try, unless your home also happens to have a more or less air-tight basement with literally tonnes of tea and 30C+ temperature.

What you can achieve with McIntosh’s setup, however, is storage that is far too dry. They can seriously damage the tea, and yield horrible results. Quite a few Kunming stored tea that I have tried that have been there since the early 2000s have similar problems, but the desert treatment that I’ve tasted takes the cake in terms of dryness damage. Not all Kunming teas are terribly stored, but many are. The worst is when they’re exposed to high levels of ventilation and dry air – it sucks the moisture out of the tea and will never change into anything decent.

What people forget, I think, is that when the term “dry storage” first appeared, it referred to teas such as the 88 Qing, which was stored naturally (i.e. without traditional ground storage treatment) in Hong Kong in an industrial building. There’s no dehumidifiers, no air conditioning, and only minimal air circulation. Mr. Chan only opened the windows on drier days, but given that in Hong Kong, most of the year the relative humidity is over 80%, when you say “drier days” it’s still quite wet by the standards of many places, and way wetter than the 65% upper limit that McIntosh has proposed, not to mention quite a bit warmer as well. And even then, the 88 Qing was, until maybe about ten years ago, still very young tasting and not particularly nice. It’s only in the past ten years when it really turned into something more fragrant and drinkable. That’s storage under Hong Kong, natural conditions. Under low temperature, low humidity conditions, it would’ve taken considerably longer.

Paragraphs like the following are particularly misleading:

“There are times when I have received a new shipment and have wanted to jump-start the microfloral growth after its been sitting on a boat for a few months covered in bubble-wrap, so I will bring the humidity up to 70% for a short period to speed up the fermentation process. I only will do this for abut a week, since if left longer there is a chance that mildew could form. Personally, I do not enjoy wet-stored tea, so I avoid high-humidity storage.”

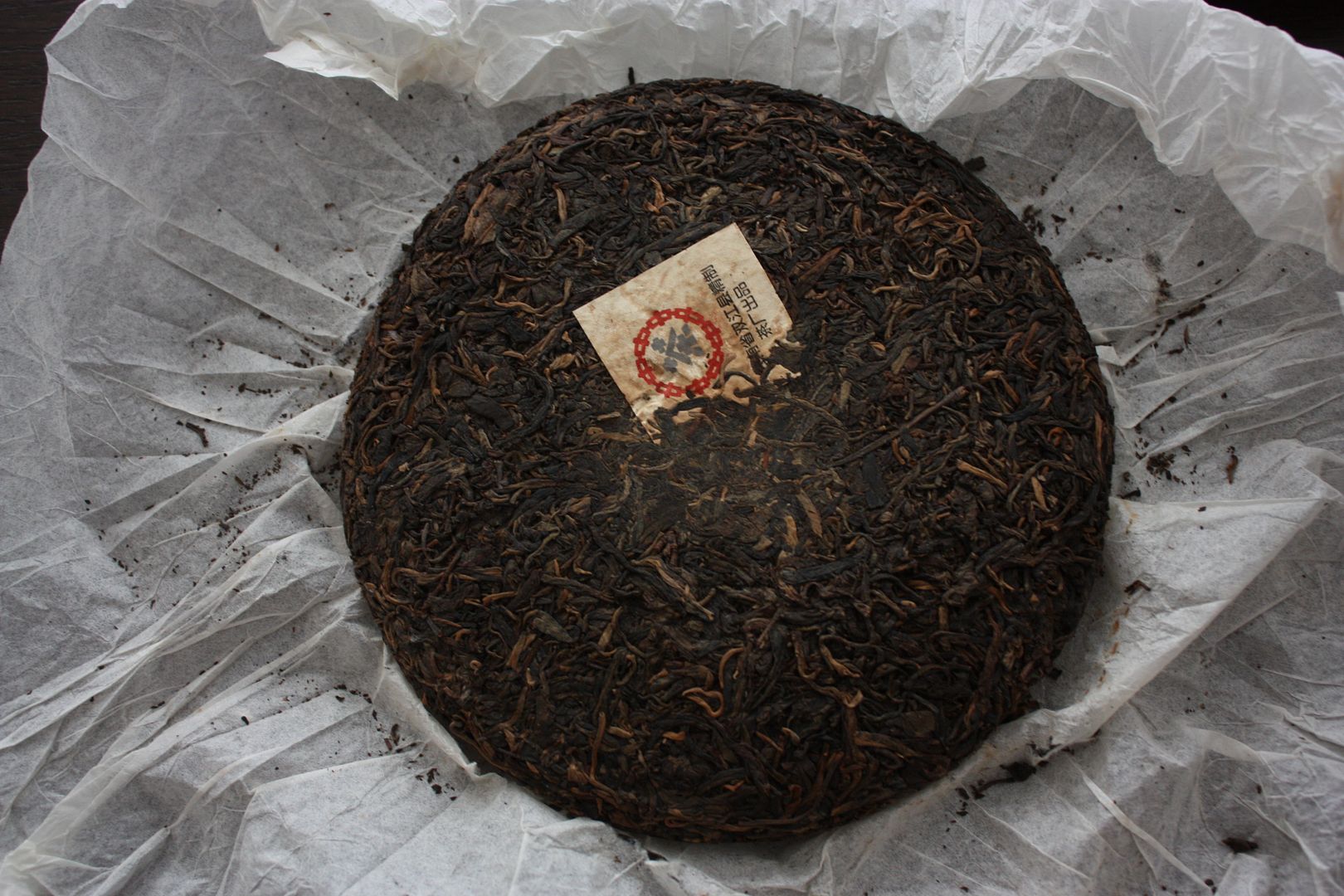

Pumping up humidity for a week to 70% for a tea will do absolutely nothing in terms of long term aging, especially if the temperature stays at something like 20C, which is typical of a heated home in the US. I have a cake that I’ve been leaving out in the open for about three months now because it was stuck in some plastic wrap for a long period of time. Relative humidity has been around 95%-98% for the past two weeks with temperature fluctuating between 18-25C, and the cake has exhibited no evidence of any mold or any other abnormal growth. The fact of the matter is, unless you put your tea right next to an open window for weeks when it’s raining nonstop and temperature is hitting 25C or higher, the ability of your tea to grow mold is not exactly high. I’m not saying it’s not possible, but relative humidity of 70 or even 80% is pretty safe unless it’s getting quite hot outside. Overdoing it on the low end, on the other hand, can basically stall any and all aging and will result in teas that change very little over time.

I think what needs to be rectified is the confusion of different terms, and substituting “traditional” for “wet” and “natural” for “dry is a good place to start. There also needs to be a recognition that many of the old teas that we consider great by the tea community at large are, for the most part anyway, stored under conditions that might be considered “wet” in some circles but which are actually what should be just called “natural”. To “Keep your investment safe”, as McIntosh puts it at the very beginning of his post, there needs to be growth in the value of the investment itself, and not just preservation of the status quo or even a decrease in its value. Aging doesn’t happen without temperature and humidity, and so trying to keep humidity down in a temperate environment is almost counterproductive in terms of trying to get good, aged tea ten years down the road. What you might end up with is a lot of wasted time and teas that aren’t particularly good or aged. Regretting the lost ten years will cost considerably more than regretting the money you spent on the tea.

I should hasten to say that I have had and liked many teas that have been naturally stored – I am, by no means, a traditional-only type of tea drinker. In fact, most of the cakes I have are natural storage only since I purchased them, or even since when they were produced. I do, however, find much fault with the idea that’s sometimes propagated on the internet that natural = dryness. Even my friends in Beijing, who a few years ago were very wary of traditionally stored teas, are now trying very hard to find ways to add humidity to their storage precisely because they now recognize that the natural environment in Beijing tends to produce poorly stored teas (dryness + coldness). To speed things up, they’d add water in bags in closed plastic boxes in order to produce something better. Even that doesn’t produce mold. The worry, therefore, is really about dryness, not wetness. It’s easy to spot tea that is starting to grow mold and even easier to rectify such a problem – just reduce humidity and temperature, and you’re good. The cake I found growing mold in Taiwan has had no problem since – it’s aging just fine, even though it had a little bit of growth for a short period. Spotting teas that are stored too-dry and hasn’t been changing much is considerably harder, and the only thing that can fix that is time and effort. If you are drinking your tea regularly, chances are you’ll spot the mold long before it festers into anything serious. That’s how I learned to stop worrying and love the moisture.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

I took you at your suggestion and have been reading some of your old post-Covid posts. I haven’t been to…