According to the folks at Steepster, you should love the website for six reasons.

1) It’s an online tea journal – this is the only point I agree with. It’s probably a pretty good and stress free way to keep a journal of the teas you’ve tried, which I personally think is a good way to help you learn and develop your tea palette. Trying new teas and writing down what you think about it is an important process that helps you think about what you just drank. So far, so good.

2) It’s a different way to discover new teas – ok, hard to argue with that, it’s new anyway, but at the end of the day, you have to buy and drink it. The problem is not so much that it helps people find new teas – yes, it does that to a degree, by showing you things that may be similar, at least according to their algorithm. But their reviews don’t seem to allow pictures, and usually there’s only one relatively useless picture of the tea, so to get anywhere, you still need to head to the vendor’s page to find out more about the tea. Unhelpfully, Steepster doesn’t link you to the vendor’s page for the tea, but only to the vendor, so you have to go through the trouble to find the tea anyway. While for some vendors this is easy to do, for others it’s a non-trivial task, especially if the vendor has weird categories, such as puerhshop.

3) It’s the largest – well, that’s both good and bad. The size of Steepster would make it seem like a good thing, and on some level, I suppose it is – it has more reviews of more teas than anywhere else on the web, and it benefits from its critical mass so that, right now at least, it seems like the only player in town. Other rating sites, of which I only know of one, are basically dead, which means nobody will bother to go visit.

The size, however, is also a problem. First of all, the rather endless stream of reviews on the site is more than overwhelming, and if you happen to be following a few dozen people, chances are you have no way of sorting out one review from the next. Also, for the most part, the network is pretty much anonymous – you have no idea who’s posting. The person posting a poor review of a black tea could be a lifetime green tea drinker who hates anything black. The person reviewing a wonderful Yiwu might be drinking raw puerh for the first time without telling you so, and thus describes it as tasting like a drain cleaner. You have the option to “like” a certain review, but like is more ambiguous than Amazon’s “did you find this review helpful?”. Like might mean you agree, or you liked what the person said for other reasons, or because you’re their friend… there’s no way to tell. The volume of information on teas, in written form, is completely overwhelming on this site.

It also is very unfriendly for people who reinfuse their teas multiple times, which most readers of this blog probably do. So, there’s no way to indicate what you do with your tea, other than in written form. Unless you’re the only reviewer, nobody will ever read it.

Moreover, because of the sheer volume of written information on the teas, the only thing that people actually will pay attention to is the ratings, in numerical form. That’s easy, simple to look at, and quick to comprehend. So far, so good, but there’s a problem – almost everything on the site rates somewhere between 70 and 85, which means that, as a mechanism for picking out teas to try, the score is almost entirely useless – how different is something that rates 78 really from something that rates 82, especially when each of them only have, say, 5 ratings each, three of which have no number attached?

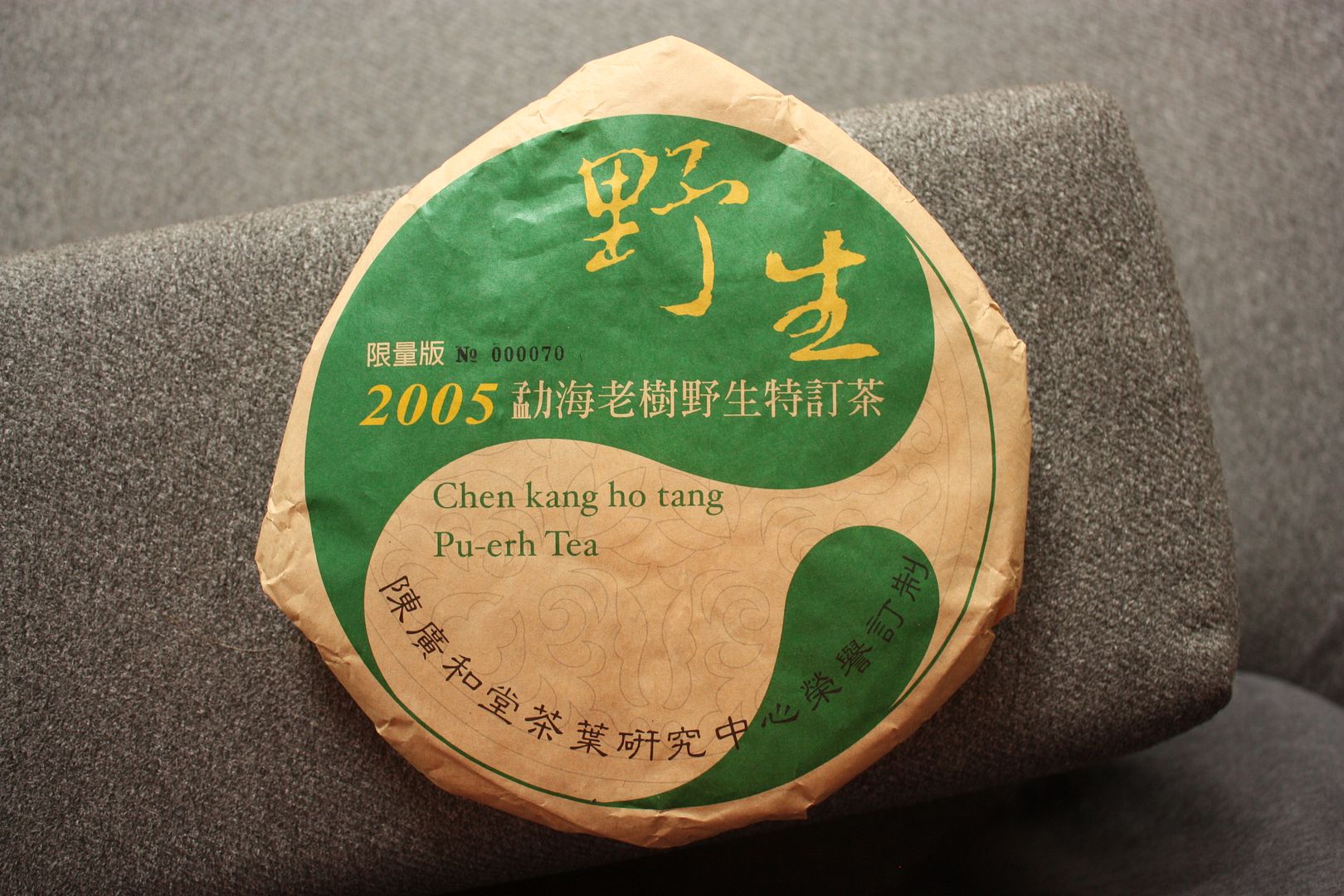

Let’s take puerh for example, one of the genre of teas that I think are least reviewed there. Sorted by rating, it takes 36 pages for you to reach the first tea rated in the 60s. That’s 36 x 28 on each page, totaling slightly over 1000 teas, many of which, I’m sure, are no long available. If you look under Menghai Tea Factory, almost everything is within the narrow band of 71-81. As a selection guide, this is more or less utterly useless.

As someone pointed out on Teachat, the name of the vendor is fungible, so that someone might enter Menghai Tea Factory, while another person might attribute the same tea to Yunnan Sourcing. Likewise, referring to what I talked about earlier about teas being anonymous, it is quite possible that two or three or four tieguanyin being reviewed (with different impressions!) are actually from the same wholesaler, rendering the ratings rather moot.

Curiously, among the top ten rated puerh are a number of teas from Verdant Tea, which as Hster has uncovered, has some issues as a puerh vendor. Is that shop really that great, or is something else going on? I can’t say for sure. It might, however, have something to do with the fact that he seemed to have distributed samples to folks on Steepster. Verdant Tea in general seems extremely active on Steepster, which might explain something. Seems like that’s a good way to goose your ratings.

4) You’ll broaden your horizons and try new teas – same as 2, really, but here they’re talking about their revenue stream, aka vendor sponsored sampling, which at the moment seems dead. Also, referring to the above point about Verdant Teas, I wonder if the key to high ratings is to send non-offensive teas to a bunch of people who’ve only had teas from Teavana.

5) It’s a place to hang out and talk about all things tea – yes, but the discussion on Steepster is exceedingly shallow, mostly because it is not designed for anything more in depth. Each review can have comments, and once in a while, you might have good comments on one thread – if you can ever find such things, that is, buried deep within each thread for each tea. The discussion board is largely useless, because it is only categorized in the most general way possible, which means that it is nearly impossible to follow specific topics for very long. If you search for a term, the search engine will completely overload you with information again, in the most useless way imaginable – by highlighting every instance in every thread where the search term has been mentioned, ordered in the number of times that term has been mentioned in each thread (at least that seems to be the way they’re doing it). This means that the longest threads will tend to be read, whereas shorter threads will drop off the radar. That’s great if you’re looking for something exceedingly specific, but if you just want to find some discussion on, say, sencha… good luck.

6) It’s free. Well, it better be.

I’m not trying to rain on someone else’s parade, but Steepster, while it is a great tool for someone to keep a personal log of teas to drink, fails on the sharing and discovery part of the equation. Is there a better way? Perhaps, but I think to start it might be more useful to introduce/tweak features that will result in more depth in the comments, notes, and discussions. Right now, reading reviews on the site is like reading a stream of consciousness writing, much of which is completely useless to anyone other than the drinker. The scores, likewise, is not very useful as it is. It doesn’t even really help you weed out teas, unless perhaps the ones that are universally hated, but those seem to be few and far between. Lastly, it might help to, for example, be able to toggle whether or not a tea is still available – listing a bunch of teas that are no longer available high on a list when you click “teas” really isn’t a good way to introduce more people to good tea either.

I’m not sure if there’s the right balance of information and quality, but right now, Steepster is high on information, but low on quality – you get a lot of stuff, most of which is noise, and it’s set up in a way that makes it difficult to filter out the noise. I think something like TeaChat, flawed as it is and hampered by an ancient discussion board engine, is nevertheless in some ways a superior forum for talking about teas than the more newfangled, social-media craze inspired Steepster.

Addendum: Some, fans of Steepster, for example, may see this as an out-and-out attack on the site. I have zero financial or personal reason to hate the site – I signed up a while ago hoping that it will be a good forum for more discussion, but came away pretty disappointed. I think there is no progress if there’s no criticism. I’m not saying I’m the one qualified to do it, but on this blog, I tend to say what I think without dressing it up too much. As I’ve mentioned, I think Steepster is a great tool for one purpose – keeping the journal of teas you’ve drunk. I hope the site’s creators can improve on the other aspects of it so that the users there can engage in tea more deeply, maybe even without knowing it. That can come from all kinds of angles – changing their algorithm in what it recommends, improving the way comments/notes are displayed and scored, organizing the discussion page using tags, instead of just what looks like an unfiltered stream of threads on unrelated topics, etc. There is a lot of space to improve upon the site now that they’ve gotten people to use it – and don’t do what Digg did and screw everything up with a drastic revision that everyone ends up hating.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

I took you at your suggestion and have been reading some of your old post-Covid posts. I haven’t been to…