Vendors, read this.

Languages in East Asia are tough, at least for foreigners. They are some of the most difficult languages to learn in the world, and for tea drinkers who don’t speak or read such languages, they can be a bit of a pain to navigate. Since names for teas are already such issues, with vendors naming their own teas and also the confusion and lack of oversight of tea nomenclature. It doesn’t help, however, when romanization is itself an issue. This is more of an issue for Chinese and less so for Japanese, since there the romanization is pretty standard. Korean romanization can be a little weird too, with different competing systems (Jeolla in Revised Romanization vs Cholla in McCune–Reischauer, for example), but since Korean teas are, let’s face it, a relatively small universe with better sourcing information generally, I’ll ignore its issues for now.

For those of you who know Chinese, you probably know that there are two main romanization systems, Wade-Giles and Pinyin. Up until the early 90s, pretty much everyone used Wade-Giles except those in Mainland China, who used Pinyin. Then things flipped, and everyone started using Pinyin, and Wade-Giles is increasingly dropped with the exception of Taiwan, which finally adopted Pinyin two years ago. These are partly for political reasons, and partly because, well, a billion people can’t be wrong, I suppose. I personally reserve a special hatred of simplified characters, because in the simplification process much of the meaning of the proper characters are lost, but I realize that many people now simply cannot read proper characters, unfortunately.

Anyway, with two romanization system and the relatively recent date of conversion, you can imagine there are issues with their usage. The problem is further complicated by two things: 1) conventions from the past, and 2) the fact that many Chinese people, especially those from Taiwan and Hong Kong, never actually learned any romanization system at all. Chinese, as you probably know, consists of characters that do not have phonetic indicators – meaning that by looking at the characters, you can’t tell how to pronounce them. It’s awful for people trying to learn the language, but it’s great for the purpose of keeping lots of people who don’t use the same dialect sharing the same written language. For all these romanizations that we’re talking about, we’re only concerning ourselves with the use of standard Mandarin.

So we’ve got two main romanization systems, but a fair number of people who don’t really know either, and a lot of vendors who probably don’t know much or any Chinese, as well as the use of older customary romanizations that persist. One of the most obvious and common old conventional spelling that still exists today, as related to tea, is the use of puerh instead of the Wade-Giles p’u-erh and Pinyin pu’er. I use puerh, instead of the Wade-Giles or the Pinyin version. Another common one is tikwanyin, which in Wade-Giles should be t’ieh-kuan-yin and in Pinyin tieguanyin. One reason people have dropped Wade-Giles in favour of Pinyin is because Wade-Giles has finicky rules regarding the use of apostrophes, which are essential for accuracy, and also hyphens. Without those, or getting those wrong, renders Wade-Giles rather useless. Pinyin only has issues with apostrophes, which is easier to deal with and errors are often not fatal (although still frequently wrong).

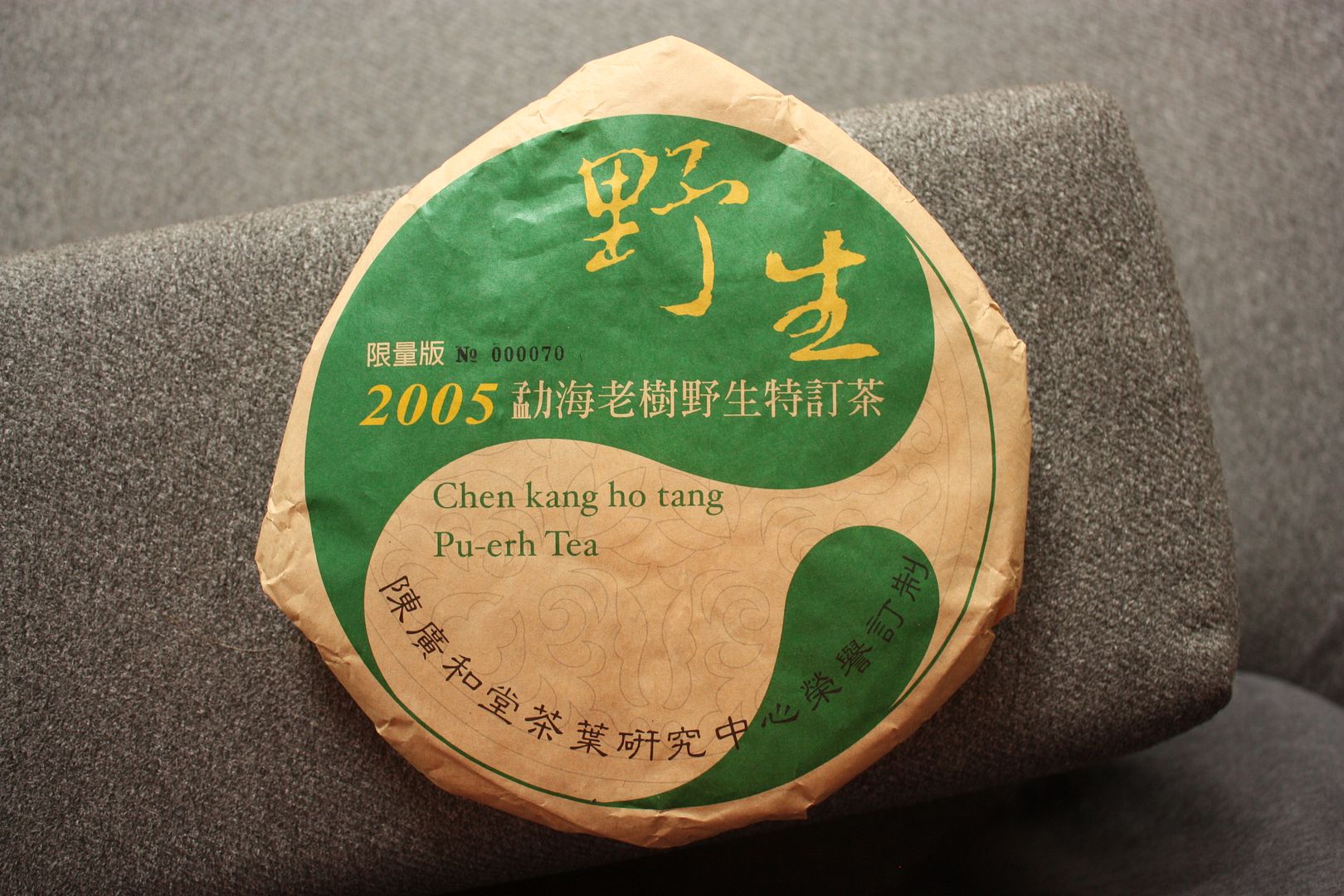

Pinyin also includes strict rules with regards to how to separate words. Since Chinese is character-based, it is very tempting to put everything into separate characters and just be done with it. Using the cake from the last post as an example:

The two big words are “yesheng” or “wild”. Then, above the 2005 is “xianliangban” or “limited edition”. After the 2005 are “Menghai laoshu yesheng tedingcha” or “Menghai (region) old wild tree special ordered tea”. At the bottom is “Chenguanghe tang chaye yanjiu zhongxin rongyu dingzhi” or “Proudly ordered by the Chenguanghe Tang Tea Research Centre”. Note, of course, the nonsensical “Chen kang ho tang Pu-erh Tea”.

Now, imagine if the bottom row is all separated (and capitalized, as is often done for reasons unknown) “Chen Guang He Tang Cha Ye Yan Jiu Zhong Xin Rong Yu Ding Zhi”. What’s going on is that by separating everything, it becomes very difficult to tell where one word ends and the next begins. When romanizing, one of the things the person doing the romanization is splicing the words into sensible units, following the rules I linked to above. If I see a row of romanized characters all separated into individual syllable, I often need to see the Chinese original to know what I’m looking at. Properly romanized, however, it is usually quite easy to figure out what we’re dealing with.

One of the worst offenders of romanization confusion is Hou De. For example, the puerh brand Xizihao is routinely romanized as Xi-zhi Hao (finally fixed in some 2011 new listings, but persist for the older ones). There are no hyphens in Pinyin, and no X in Wade-Giles, so this is really neither. Hou De routinely does this sort of mixing, but Guang’s certainly not the only one. In his defense, he probably never learned Pinyin, having grown up instead on zhuyin fuhao. Other vendors mix in capital letters when there should be none, separate words randomly, mix in Wade-Giles from time to time, or simply spell things wrong. Babelcarp has a truckload of such misspellings, helpfully linked to the most widely used one.

Another issue is more simple – some vendors choose to give you the name of the tea in translation, while others give you the name in transliteration. Biluochun and green snail spring are the same thing, but you wouldn’t know it unless you’ve learned that somehow. Likewise, you can see Keemun, the old conventional name for Qimen, often on websites and teas and what not. Qihong is Keemun black, but again, you wouldn’t know it unless you somehow already knew.

While most people can figure out that puerh and pu’er are the same thing, it’s harder when the difference is between tikwanyin and tieguanyin, or even oolong vs wulong. Ideally, we’ll all use the same thing, so there are no problems, but I choose, for example, to use oolong instead of the proper wulong romanization because of accessibility – the same reason why puerh is used instead of pu’er on this blog. Very often people will find oolong being the word on vendor pages, not wulong, and might wonder what wulong is when in fact it’s the same thing they’ve always had. I also thought about switching wholesale to use Pinyin exclusively, but the thought of somehow having to go back and fix past listings stops me. I suppose the only way for a consumer to wade through all this is to arm him/herself with some knowledge of Chinese, so that one’s not too reliant on vendors’ proclivities. Vendors can also help by using more Chinese in the websites – it never hurts, and in this day and age, easy to do. Unless, of course, if they decide to rename their low grade Yunnan black tea Golden Peanuts, or something.

Addendum: Sometimes I forget the original impetus for writing these things. Jakub, helpfully, reminded me with his comment. For things like proper names, one should string them together. So, Yunnan province is Yunnan Sheng. Menghai county should be Menghai Xian. Yiwu mountain should be Yiwu Shan, not Yi Wu shan or Yi Wu Shan. Gaoshan Zhai, or Guafeng Zhai, or any other village, are a little more ambiguous. Zhai, in this case, is really “village”, “hamlet”, or literally, “stockade”. So it should be treated the same way as sheng (province) and shan (mountain) and separated from the name.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

I took you at your suggestion and have been reading some of your old post-Covid posts. I haven’t been to…