One of the most confusing things about buying tea is that there is virtually no naming scheme and standards. I can go buy some green tea from a wholesaler and resell that as “jade green spring”, which sounds awfully like biluochun “green snail spring”, and perhaps lead you to think that it might have something to do with biluochun, even though my tea could be some cheap Sichuan green of no notable character. Tieguanyin from Fujian and tieguanyin from Taiwan are entirely different beasts — the ones in Fujian are generally named for the varietal of tea plant from which the tea came, while in Taiwan tieguanyin also includes specific sets of production procedures. Likewise, Longjing is a famous tea, and is supposed to be from the Hangzhou area, but somehow, Taiwan has Longjing too, and no, Taiwan’s Longjing does not taste anything like the mainland version, at least the good stuff. And then you have things like “Zhejiang Longjing”. And let’s not even get into puerh naming conventions….

It seems like what really needs to happen, at least with Chinese tea, is a strict regulatory regime that makes it possible to tell something about a product when it comes to its name. When I see the word “longjing” I should know that it is coming from a defined area, with a defined characteristic, and maybe even certain defined manufacturing procedures. This is like how appellation d’origine contrôlée is done in France, and it works pretty well. When you see Epoisses de Bourgogne, you know what you’re getting. It’s going to stink, it’s going to be creamy, and it’s the same every time. If you put that name on, and you didn’t make it there or follow the proper rules, then you are going to get sued.

This is of course part of the problem — the lack of a robust legal system that can handle problems such as infringement on these names, and the lack of an authority established to deal with such issues. I remember reading about a Chinese town that wanted to copyright their namesake alcoholic beverage, because other people from a different town started making it, and it was being bastardized and worse, its reputation was damaged because the other product was not as good. For people whose hometown has a product which has a name-recognition value, it is in their best interest to have a system that will protect such a product.

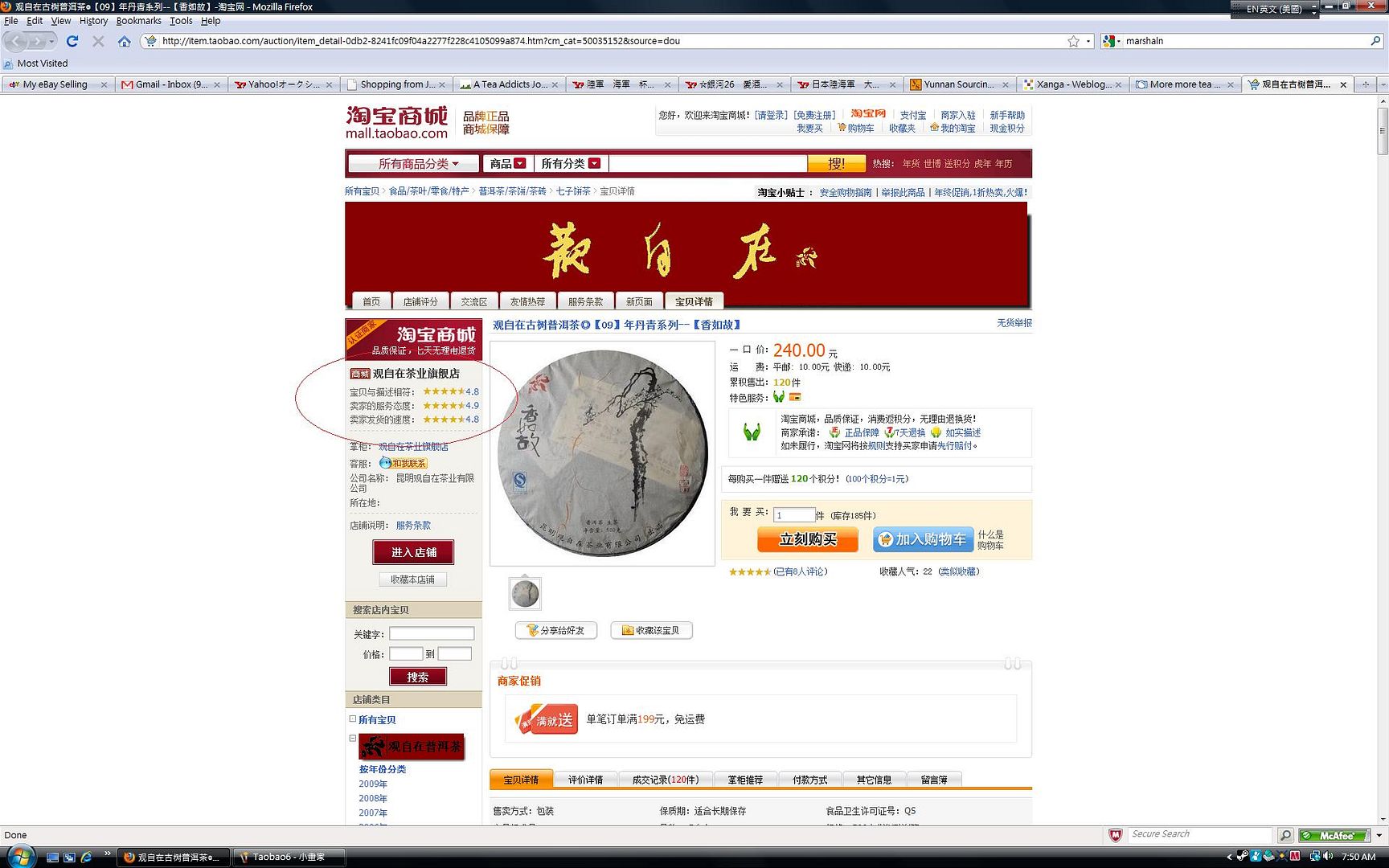

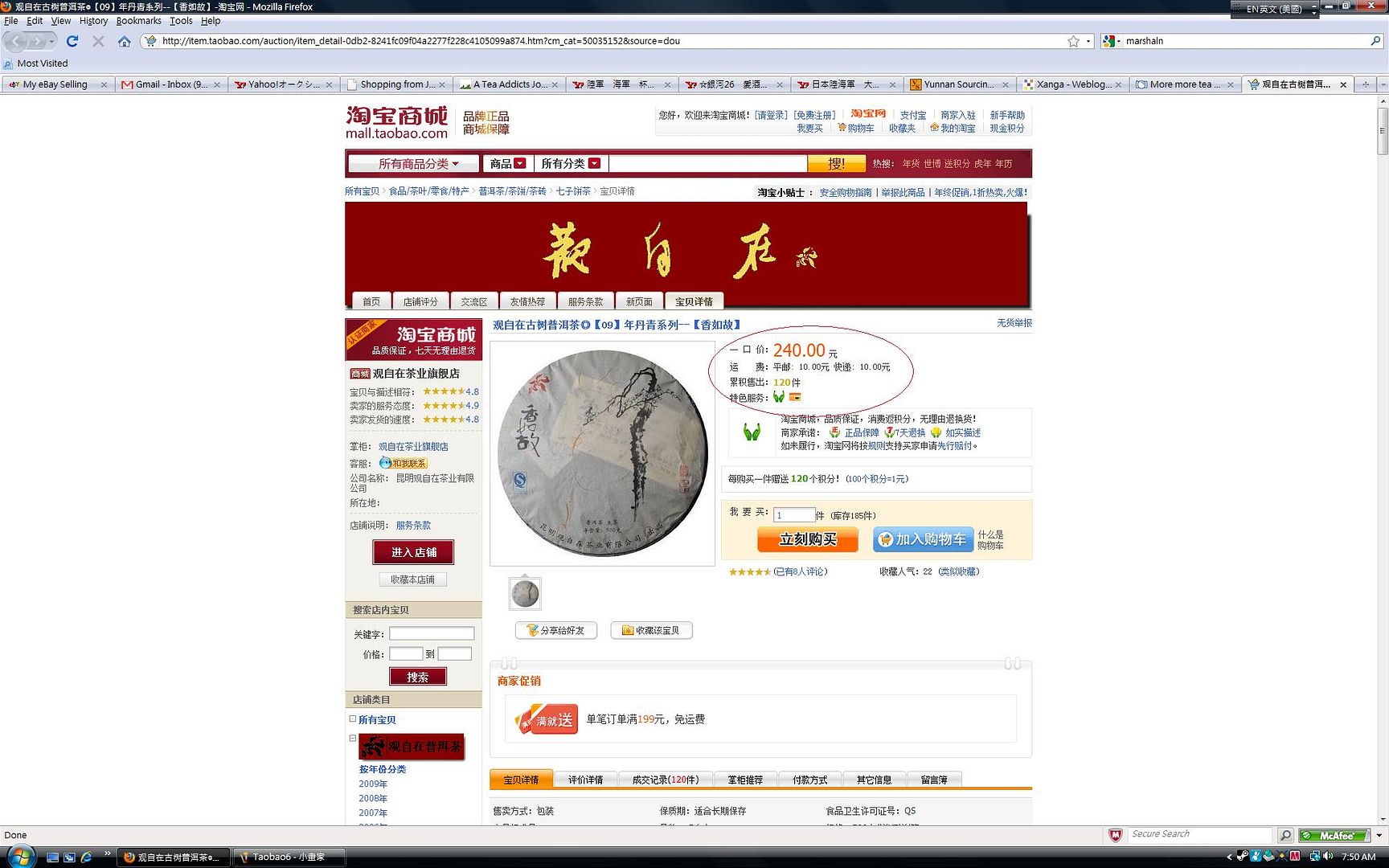

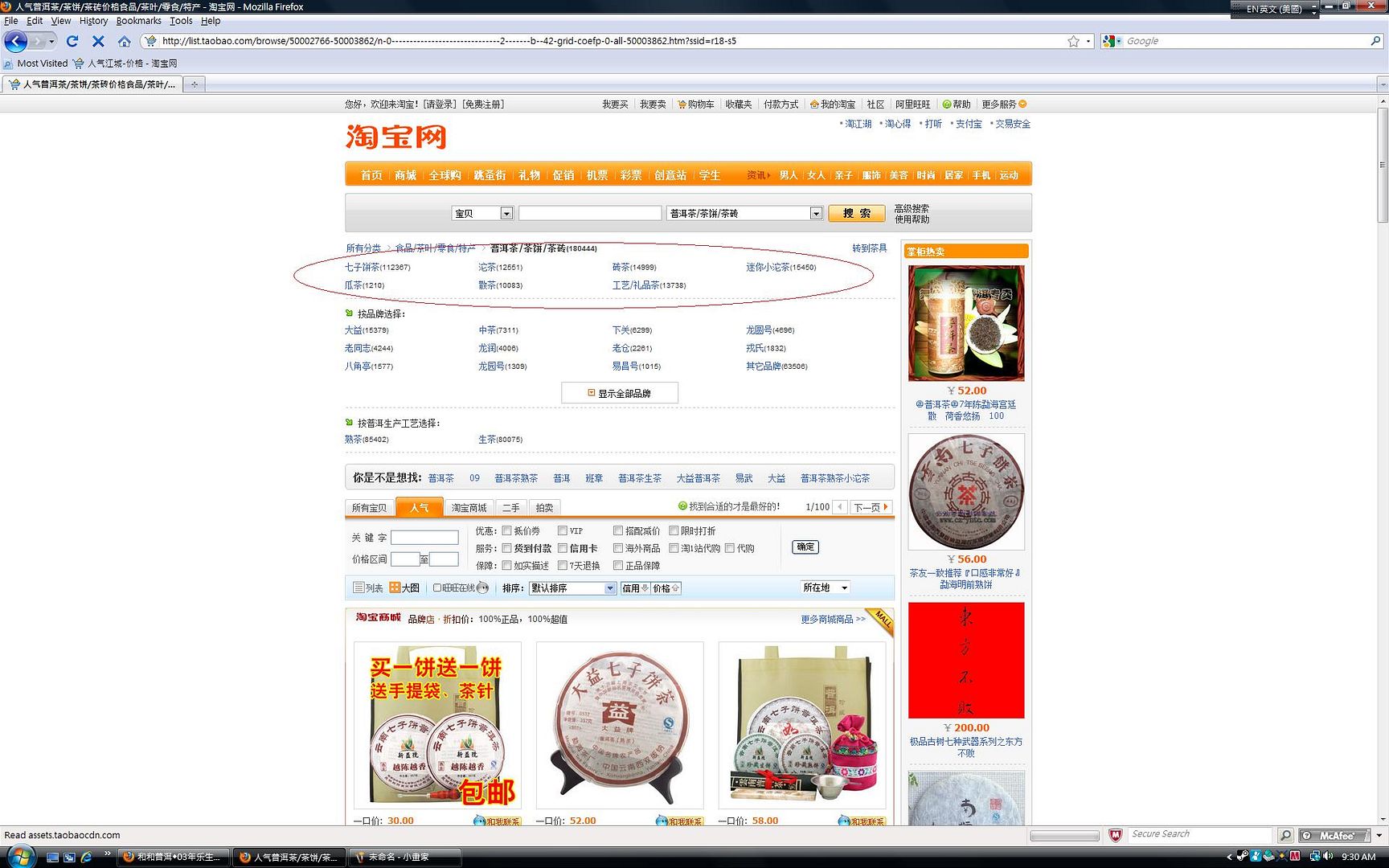

It is, of course, also in the interest of the government to do so, because goods that can command the trust of the consumer is going to be able to command a higher price. The lack of appellation control means that when I see “Yiwu” printed on the label of a puerh tea, I actually have no idea what’s in it. It could be indeed the best leaves from Yiwu, it could be really bad leaves from Yiwu, it could be leaves from other places in Yunnan, or worse, it could be from places that are outside Yunnan. There’s no way to tell, and the only way I can even guess is to drink and see what I think of it. Nine out of ten times, however, Yiwu and other famous places like it will have tea that isn’t really produced from materials made from that area, just like “Anxi tieguanyin” is often not Anxi tieguanyin at all. Really experienced drinkers will know the difference, but for the vast majority of consumers, no such possibility exist.

One of the inherent problems with tea is that it is often made by small farmers, and sold to larger distributors/consolidators/wholesalers who blend, process, and resell the tea to the consuming public. The leaves themselves are anonymous, and farmers are usually only selling bags of tea they carried to the factory with no distinctive marker of any kind at all. When you look at the raw leaves, you really can’t tell very well whether it’s from Yiwu or not.

The Taiwanese have come up with a rather interesting method of dealing with this problem, namely, regular tea competitions among farmers. Farmers are asked to submit batches of tea for these competitions, and the teas are then graded, winners announced, and the teas are then resealed in government authorized packaging with the grades accorded to the tea. The point of these competitions were twofold — to encourage better tea, of course, but also to grade and sell them in a way that guarantees some level of quality. For an entry into the competition, the farmer has to submit a certain amount of tea (13.2kg for Lugu) and the judging panel basically takes a random sample out of this batch to evaluate the tea. The whole batch eventually gets sold, and because of the labeling and the grading, they are usually sold at prices much higher than they would otherwise command without such certification.

Now, doing so would be hard for all levels of tea, and in all fairness, there’s probably no good reason why this needs to be done for the large scale, commercial, and mass-consumed tea that slosh around the market every day. At the same time, some basic form of appellation control that at least gives a modicum of origin assurance would be nice. Just like how for wine there’s AOC, Vin de Pays, Vin de Table, etc, one could imagine such stratification for different kinds of tea. Some farmers might go for the highest rating and aim to produce high quality, but possibly lower yield, tea, while many will be content to make tea for the mass market. Some will do both, and it is up to government authorities to build an infrastructure to support this kind of choice. What we have right now, however, is nothing, and nothing is damaging the entire market.

Western buyers are not alone in this either, as Chinese buyers are just as confused as everybody else. Most experienced tea people know that when you buy Dahongpao, oftentimes the tea in the bag is not really Dahongpao. On top of the varietals you have all kinds of other things, such as Monkey Picked, etc, that are often used by shops to denote their own blends or processes. If there’s an appellation control, at the very least they can tell you it is “roasted in house using x leaves” or something along those lines. As it is, we have none of that luxury. For the Western buyers who have to deal with names like Snow Monkey, Leopard Monkey, Naked Monkey, or whatever else, the situation is only worse.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

I took you at your suggestion and have been reading some of your old post-Covid posts. I haven’t been to…