A fellow drinker way back in 2005/6 was hster, whom some of you may remember from the LJ Puerh Tasteoff that BBB organized back in the day. Seems like hster has restarted a blog after a long absence from the online tea scene, and has posted, among other things, some sage advice for those just starting out. It’s worth taking a look here.

Entries from May 2012

Patina

May 29, 2012 · 8 Comments

There’s something about slowly using a yixing pot, and the accumulation of a patina after extensive use. I bought a group of five shuipings recently at a local shop, and have only been using one. After using it for no more than six or seven times, the one I use already looks different from the rest – its colour has changed a bit, and the surface seems smoother.

It’s not obvious – given the lighting and the inherent limitations of my poor photographic skills – that they’re all that different. The one on the left, however, is the one I’ve been using, while the one on the right has never seen any tea. I suspect at least initially, what happens is that the initial seasoning and usage of the pot washes away much of the residue of manufacturing. Also, some of the particles that may be attached to the surface loosely are also removed after having water poured all over the body of the pot. After a while, you have the patina building up, so much so that it forms a distinct surface on the pot itself.

Then there is the natural staining that happens over time, and which is hard to replicate otherwise. Fake pot dealers will normally try to mimic this by using all kinds of stuff – soy sauce, ink, or shoe polish. None quite work and will always look fake, lacking the natural lustre of tea. My lion pot, for example, was really dirty when I bought it. I cleaned it. Then, after a few years of use, it is now dirtier again – but at least this time I know it has been soiled by nothing other than tea stains.

I don’t really believe in spending too much time polishing my pots or rubbing them much – I just let the patina show up naturally, through use. I don’t even pour much tea at all on my pots. Eventually, with use, the pots will start to change and age. That’s part of the fun of using yixing pots, and with pictures, you can really see the changes that take place over time.

Drinking with your body

May 23, 2012 · 17 Comments

My friend L from Beijing has come and gone for a quick visit to Hong Kong. I took him around town to take a look at various older shops here, and drank some interesting things along the way, such as an aged baimudan that’s quite good and some 40+ years old tea seeds that have an interesting fragrance to them. If you look hard enough, you can find interesting things in all kinds of places.

L also brought some things himself, including a cake that he sells, made by the same people who were behind 12 Gentlemen cakes that I tried in 2006. They have now moved to a different philosophy of tea making, and L recently went on a trip in Yunnan with them, visiting their own maocha production facility (they only buy fresh leaves, not maocha) and talking to the producers. The idea behind the cakes is that the cakes are produced with the intent to minimize the aroma and fragrance. As L quotes the maker of the tea, “beginners drink tea with their nose, experienced drinkers drink with their mouth, and the connoisseurs drink with their body”. They’re taking it to the next level, so to speak, by trying to make teas that don’t possess fragrance or aroma, and in so doing taking out the distractions. More on their tea another day.

This is by no means a unique insight -Â I have both heard similar things from others, and have also witnessed this myself. It is indeed true that beginners tend to drink with their noses – fragrance, above all, is what they focus on. This explains why jasmine is a perennial favourite of so many casual tea drinkers, and why a light oolong or green teas tend to be “gateway” teas that get people in the door – they’re fragrant and they’re nice to drink. Then, as you progress through the collection of more experience and the like, you start learning about the nuances, and the mouth comes into play – the body of the tea, whether it stimulates the various part of the mouth, the tongue, whether it is smooth, etc. Then finally, you get to the point where you are drinking the tea with your body, where the taste, the fragrance, etc are all less important than how it makes you feel. You can call it qi, even though I dislike the opacity of the word because it means little to those who hasn’t experienced it, or you can call it energy, or whatever you fancy. Yes, every tea has qi of some sort, although I don’t think many will actually be strong enough for you to experience it. In fact, any time a vendor talks too much about qi it is probably a sign that s/he is up to no good, and the tea is really not very good at all, which is why I prefer not to use the word at all – it needlessly adds to the learning curve and there’s a high potential for the Emperor’s New Clothes here.

Yet it is true that beyond a certain point, what distinguishes between a good tea and a great tea is the energy the tea has. Fragrances can be manufactured – they’re mostly the product of the post-plucking processes and can be easily manipulated by the tea processor who’s skillful enough to do the deed. It is much harder to fake energy. The best teas will give you a sensation of a current running through your body, but not in a way that makes you nervous, jittery, or uncomfortable. The 1997 brick I tried recently that made everyone at the table feel jittery was not a good tea in that sense – it was not something I’d consider drinking any time soon, if ever. On the other hand, genuine, good old tree teas tend to provide that energetic sensation in a way that is pleasing and comfortable. It’s hard to describe it, but once you’ve tried it you won’t forget it.

So with that in mind L brew me some tea. We tried a number of things over the course of two days – one of the produced cakes, some maocha they collected (with him seeing in person the entire process from plucking onward) and also a number of other things. The cake that they produced was, indeed, very bland in the “no fragrance, no taste” sort of way, but it does interestingly enough have some decent energy. He insists on drinking the tea quietly, without comments, which of course helps you focus on the tea in question, but once again, might cause an Emperor’s New Clothes problem.

I think in general this is a good idea – experimentation, even failed ones, are probably good for tea in general. Someone who has a new idea and who wants to produce a tea based on it, and actually having the ability and the skills to do so, should be encouraged to do his best. I still remain a bit skeptical of the end product, but I certainly applaud the general direction in which they’re going. I would also much prefer to drink their bland tea than a newly produced tea using boring old plantation leaves. Now, if someone can figure out how to satisfy all three parts, then you’ve got the perfect tea.

Categories: Teas

Tagged: health, musings, skills, young puerh

Not paying the resale premium

May 18, 2012 · 12 Comments

Puerh is different from most teas in a number of ways, but one of the traits that it shares less with tea (other than liu’an) and more with wine is that puerh holds resale value, at least in the compressed form. When you have a cake of puerh, you can resell the tea to someone else quite easily, and if you have held it for a while and the cake is famous, the cake can resell for quite a premium. I was talking to some friends last weekend about tea while we were drinking together at a local teahouse, and they mentioned that they bought some Yellow Labels back in the day (about 10+ years ago) for 500 HKD a piece. That tea is now easily 20k HKD depending on the condition of the cake, so it’s quite a markup over the years. While they may not be able to fetch that kind of price, it is quite safe to say that someone who bought tea twenty or even ten years ago would’ve made a lot of money keeping it.

This is drastically different from most teas, which, upon being sold, holds little value. Sure, you can resell 200g of whatever oolong you bought from some online shop probably for little loss if you grew to dislike the tea or simply want something else. Try doing that with 2kg, or 20kg, however, and you’re in real trouble – it’s no longer feasible, and chances are nobody will take it off your hands without a substantial discount. With puerh, that illiquidity haircut is much lower than that of other teas.

This also means that when you buy a cake of puerh, you’re also paying the premium that comes with the liquidity of the underlying asset – the tea itself. When you spend 15k HKD to buy a cake of Zhenchunya, for example, you know that you can quite easily resell the tea to someone else for pretty much the same price. This is also one of the reasons, I think, why teas from Dayi tend to trade at a premium to other factories. Of course, with Dayi tea we more or less know what we’re getting, and there’s definitely a “trust” factor involved here. However, there is also the case that Dayi teas are among the most liquid of puerh teas on the market today, which therefore commands higher prices. This is why there’s the very strange phenomenon, observed by friends in the mainland who deal tea, where one jian of Dayi tea costs more than 42 loose cakes (Dayi jians are all 6 tongs now) of the exact same thing – the jian is more valuable because 1) the packaging of the whole jian gives it one extra layer of anti-counterfeit measure and 2) the jian is the basic unit of trade for tea traders, whereas once you’ve broken up the jian you have to sell it retail, and there just isn’t all that much demand, retail, for this sort of tea.

So when you buy an aged cake, one of the things you’re paying for is this resale premium. You are, in other words, paying for the ability to sell it at a later date. What if you can strip this value away and not pay for it?

Well, there are ways, one of which is to buy broken up pieces of cakes, which are always substantially cheaper than the whole cake itself. Some of these, when you can find them here anyway, are quite tasty and well worth the value. Another option is to buy cakes that are damaged in some ways so that they are no longer sellable in the same way a whole cake with original wrapper, etc, can be sold. Some of these were used as samples. Others were just damaged. Still others… who knows. For the end user of tea – drinkers like you and me – this is something that matters very little.

One of the cakes I acquired recently is in this vein – cheap (relatively speaking) aged tea because it has no wrapper, lost a decent amount of tea (it’s about 300g instead of 357g) and just generally not very appealing looking. It doesn’t mean it isn’t aged, and it isn’t tasty – it’s just no good as something to be sold to someone else, so the only people who’re going to be willing to buy them are people like me – drinkers.

You can see this is typical Menghai factory stuff (the neifei is “submarine” i.e. under the surface of the cake) with a layer of finer leaves on the face of the cake, and on the back (and inside) rather big leaves. The tea is not particularly great or anything, but it is superior to many of the loose, broken pieces that you can find, which tend to be a little lower in quality. Also, this being a whole cake, it provides a nice reference point for the age and the type. The seller claims this is about 20 years old or thereabouts. The information is, at best, sketchy. The tea has been through some traditional storage, but that was definitely a while back, and the time spent on the shelf of the seller’s store has made it rather mellow.

With teas like this, is there any reason to pay full price just to get a wrapper?

Categories: Teas

Tagged: aged puerh, musings

A Quintessential Invention

May 11, 2012 · 29 Comments

MadameN and I have co-written a paper and presented it at a local conference on the recent history of tea and tea practices in East Asia, using mostly the Taiwanese/Chinese re-invention of chayi/chadao as an example to illustrate a case where one regional, localized tradition was adopted and re-invented as a national tradition. The full paper, a pretty short affair, is available here, in the tea issue of this quarter’s China Heritage Quarterly. Other things in there might be worth a look too, so please go ahead and take a read.

Categories: Information

Tagged: history, musings

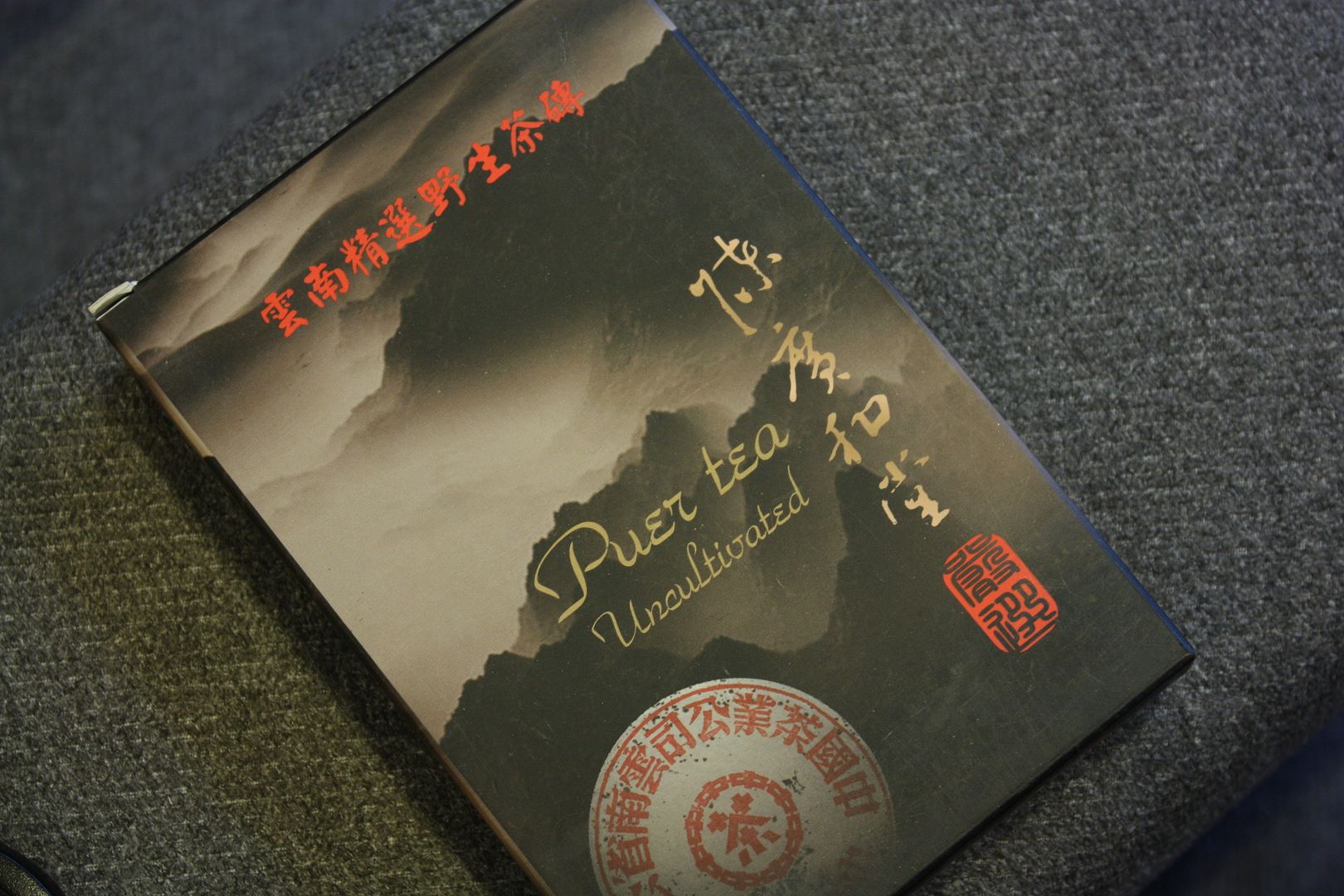

The retaste project 11: 2005(?) Chenguanghe Tang Yiwu brick

May 7, 2012 · 1 Comment

This is a brick that, I think, I bought in Taiwan while I was there doing work. I seem to remember picking it up along with a few other things, more as a curiosity piece than anything else. Back then Chen Zhitong, the proprietor of Chenguanghe Tang, was just starting to press his own stuff, so I’m not sure if this brick was his own, or if it were one of the “someone pressed it and I named it” sort of deal. I do remember it being relatively cheap, which is why I bought one.

Unfortunately, there’s a reason the tea is cheap – it’s really, really broken up, as in the leaves are very chopped. Other than the surface, which has a layer of decent looking leaves, everything in between is pretty much chopped leaves of the smallest variety – stuff you might expect in a teabag, but in a brick form. When I used my pick to pry out a piece, it was basically effortless, and the leaves more or less crumble when you pressure the leaves.

The result is rather disappointing – nasty early brews because of the high surface area, and then weak late brews because the tea has been exhausted. What you see above is the result of the wash – just lots of tiny sediments and fannings. There wasn’t a single whole leaf in there, and most of it is too fine to even make it into big factory cakes. In other words, it was the leftovers pressed into a brick. There’s a reason why my friends generally stay away from bricks unless they know it’s a good one.

Categories: Teas

Tagged: retaste project, young puerh

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

I took you at your suggestion and have been reading some of your old post-Covid posts. I haven’t been to…