This discussion happens once in a while with tea friends on and offline: what exactly is fair for a vendor to charge, and what, exactly, are they providing?

I guess first of all, we can account for the costs that a vendor has to pay to keep his or her business a going concern. This may involve a lot of costs, especially if there’s a physical store attached to the business. It might include labour, rent, electricity, water, local taxes and fees, certifications, etc etc. A store that exists only online is going to cost a lot less to run than a store that exists as a standalone teahouse in a small town, which will in turn be cheaper to run than say a shop with a nice locale and decor in an expensive city like Paris, London, or New York. The majority, I suspect, use the proceeds from online sales to subsidize their brick-and-mortar operation. Few, if any, go the other way around. Maintaining the internet store also costs money too, of course, as does the need to keep a merchant account with credit-card processing ability, website hosting (the cost of which, as I’ve discovered, is non-trivial), and other sundry outlays that are necessary to keeping up a store and running it as a business.

Then there are the costs that are necessarily associated with running a tea business. Storage, obviously, is a concern, and with that, the holding of physical inventory, which represents a time-value-of-money type of cost (holding, say, $10,000 worth of tea instead of treasury bonds costs real money, although you can argue about that point with regards to puerh). There are risks of spoilage, floods, fire, and whatever other natural disaster that may happen that can ruin the tea in question, so a certain, small amount of risk is involved, further increasing costs. Shipping the tea from wherever they’re sourced to the vendor’s own location obviously costs money too, and for tea there really aren’t many cheap, good ways to ship tea in bulk.

On top of that, some vendors may be spending a good amount of money traveling to get the tea to begin with. Some vendors seem to make multiple trips a year to faraway places in Asia, ranging from India, Malaysia, Taiwan, Japan, Korea, and China. These trips, if undertaken from North America or Europe, are not exactly cheap, and presumably, all these costs are rolled into the cost of running the business. Some vendors probably buy most of their teas from wholesalers in their respective continents, but then, if you’re an avid reader of this blog, chances are you don’t patronize these vendors too often.

What I’ve described so far, I think, are most of the normal day-to-day costs of running a tea business for vendors based in the Western hemisphere. The question here, I think, is what exactly is the value-added from these vendors?

The first thing that comes to mind is, of course, that they are making teas available that are otherwise out of reach of the average Western consumer. Flying to Taiwan or China to buy oolongs or puerh is not exactly what most people do on a regular basis, so absent that, buying it from a vendor who’s doing it for you is probably not a bad idea. That service, of course, is worth something, but then, there are a number of vendors these days that are based in Asia and who are increasingly branching out to sell to the West, since everyone recognizes that there’s a market there for premium quality teas. Also, more and more consumers in the West are taking advantage of services such as various Taobao agents and buying more or less direct from Asia. So, “making teas available” alone is, I think, no longer a compelling reason for a high premium when vendors who are based on location can provide the same services without the extra cost of travel and airfare.

The second value-added service that vendors can claim to be doing is, of course, that they are selecting out the chaff from the wheat. There’s definitely some truth in this, as there’s plenty of chaff to go around, and as anyone who’s tried to buy tea blind from Taobao would know. Sampling crap costs real money, so yes, that’s work that deserves credit. At the same time though, it is still work that can be done by someone on location. Also, I’m sure many vendors, including those traveling to Asia, are only buying from shops there, instead of going all the way to the farms in all cases. In some cases, such as aged teas, this is a necessity, since they are all held by vendors of some sort or another. In other cases it could easily be the result of convenience and cost, or of the Longjing rule at work. Either way, there are oftentimes multiple layers of vendors between a tea and the end consumer. All of these costs – both the regular running costs, as well as whatever transaction and other value-added mentioned so far, are probably reflected in the prices that the consumer ends up getting charged. None, I think, is particularly valuable above and beyond what some vendor based in Asia can do.

This is why I think what Western vendors must be able to do is to provide exclusive access to teas that are rare or otherwise unobtainable, even if you were on location. In many cases, however, I think that exclusivity is only an illusion, present because of the lack of comparison and alternatives, not because the teas provided are truly unique, great, or both. Not too many people sell real first flush longjing, for example, or a well roasted tieguanyin of top flight quality, or a well aged, 10 or 20 years old puerh cake. If they have it, and you don’t have market access in Asia directly, chances are you can’t find it elsewhere.

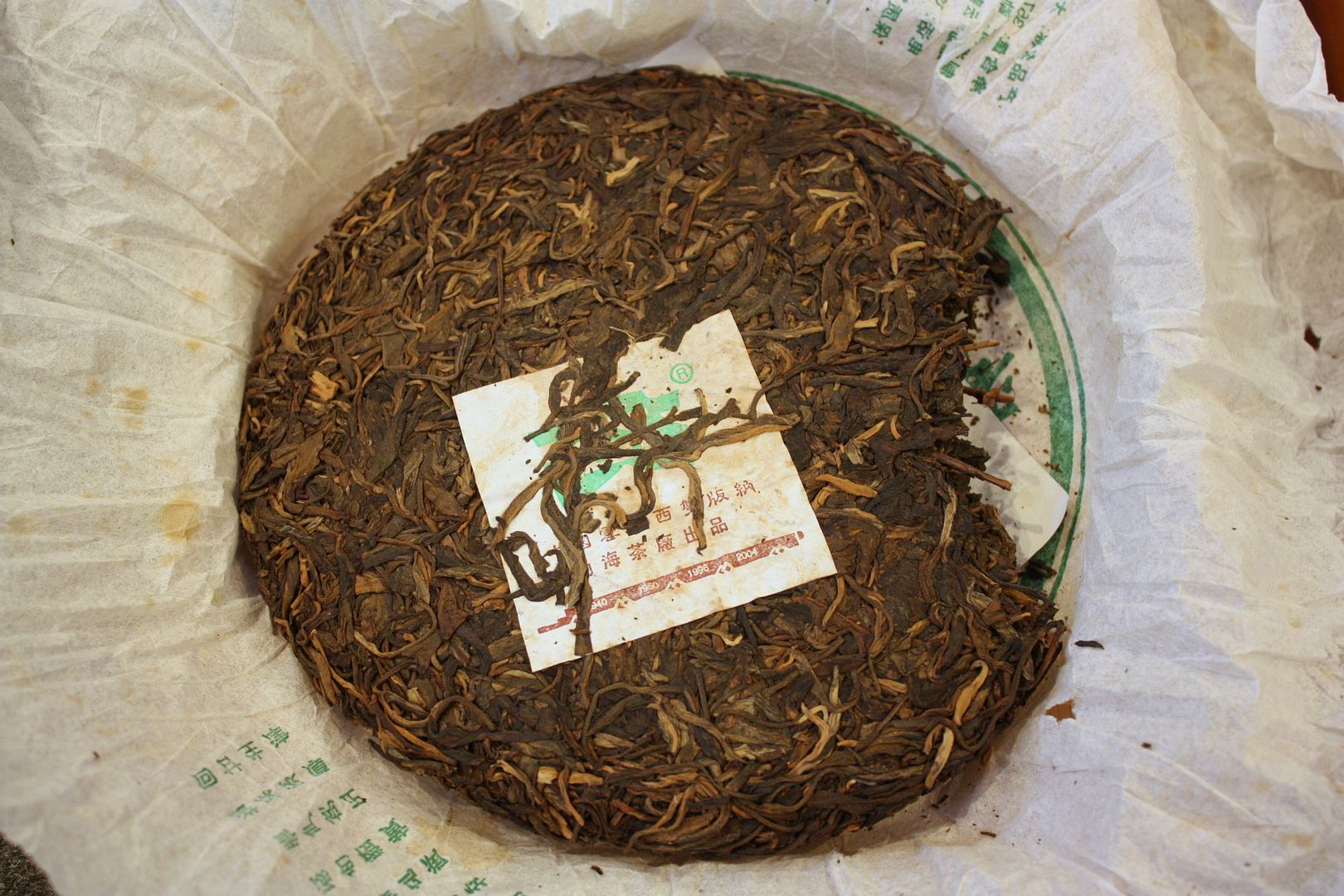

In almost all these cases, there is always a tea that is similar enough that can be had elsewhere. Exclusivity is therefore a product of a dearth of selection, rather than a real shortage of teas. Among the selection that is available, very often I find the teas to be very mediocre, especially if they are aged teas of one type or another. Among the aged oolongs people have sent me samples of which were acquired from Western vendors, not a single one has been better than mediocre, with some being downright problematic or fake. The same can be said of pre-2000 puerh, with cakes that are available tending to be the 3rd tier goods that are sold in the Asian market – the top flight stuff are never offered online to Western drinkers, so they never have anything good to compare it against. Instead, what are basically rejects from the Asian market are sold as well aged teas, which is really a bit of a shame. The only exception to this that I’m aware of is my friend Tim of the Mandarin’s Tearoom, who really has some interesting teas, but then, as it will be obvious to anyone who visits his site (so hopefully he doesn’t stop talking to me forever for saying this), there are prices to match.

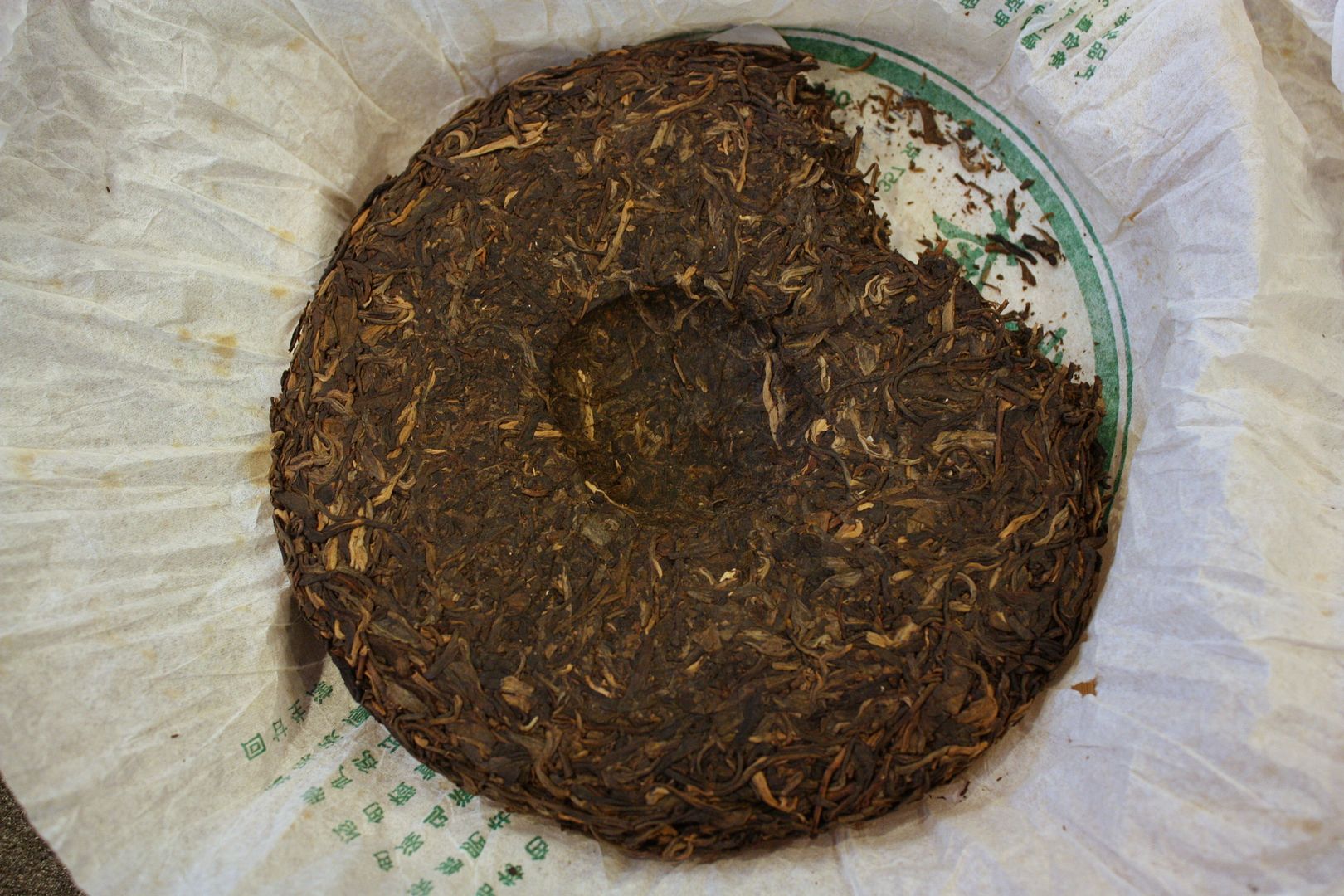

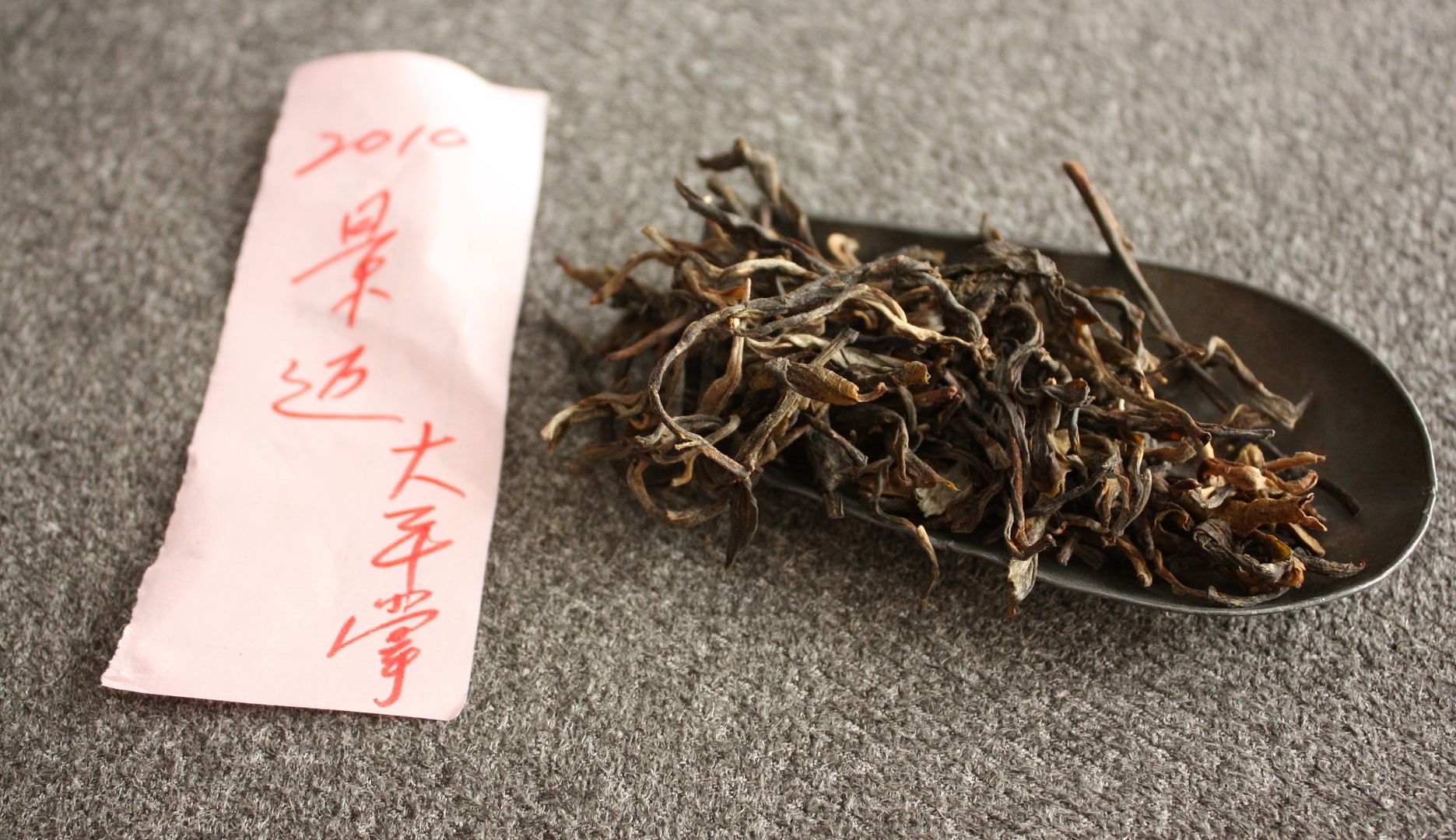

This feeling of inadequacy in terms of selection and dearth of information on such rarer teas has been reinforced since I got back to Asia this summer. Aged cakes of puerh from the 90s are everywhere, as long as you want them. Some are not very outrageously priced at all, and even late 80s cakes can be had for a relatively reasonable sum, providing that they are not hyped and famous, thus extremely expensive. Aged oolongs are never terribly expensive, if you know where to look and what to look for, but good ones take work to find. As for new teas, the range is endless, and as long as you’re willing to pay the price (which is not cheap these days with prices rising by the day in China), topflight tea is easily to be had.

I’m not sure where that leaves the average consumer without language or physical access. I guess the first thing to remember is that tea is not nearly as rare as vendors generally make them out to be. While some are indeed quite unique, if you spend time in the tea markets often you can end up with something similar within half a day of shopping. Vendors, I think, can do better in providing good quality tea at reasonable prices, given their constraints anyway, but consumers also need to work a little harder. By that, I mean that consumers need to think about what they’re drinking, and seek out alternatives to their usual vendor. Of course, how far anyone is willing to go in that direction is really an individual choice, but I think one’s experiences drinking tea will be that much richer if such issues are contemplated actively and assumptions, statements, and claims questioned. Obviously tea is a drink to be enjoyed, but at the level of connoisseurship, I think part of the enjoyment comes from critical evaluation of the teas in question.

Pursuing my last few lines from the previous post, I think chasing particular teas based on outside factors is quite dangerous, and lead you down a path of high prices and oftentimes disappointments. I just heard a story in a teahouse recently of a certain someone who “only drinks Red Label” (the 1950s puerh that now sells for $30,000 a cake). Well, sure enough, that person bought a bunch of fake or, at best, very inferior quality ones. Just like all those people who went out and bought particular cakes of puerh because so-and-so said it’s the greatest thing ever, many are now sitting on teas that are not necessarily very good and have barely appreciated above and beyond what has generally happened to the market in the past few years. Others follow this or that fad, and end up paying the most for whatever tea is “hot” at the moment, such as how jinjunmei, a rather mediocre black tea, was all the rage in the last two years and one jin of the tea was selling for over ten thousand RMB. All of these are rather senseless, and are mistakes that I think should be avoided if one were serious about drinking tea.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

I took you at your suggestion and have been reading some of your old post-Covid posts. I haven’t been to…